Hey NASA, Where Are the Records for Thousands of Space Shuttle Tiles? This Man Wants to Know

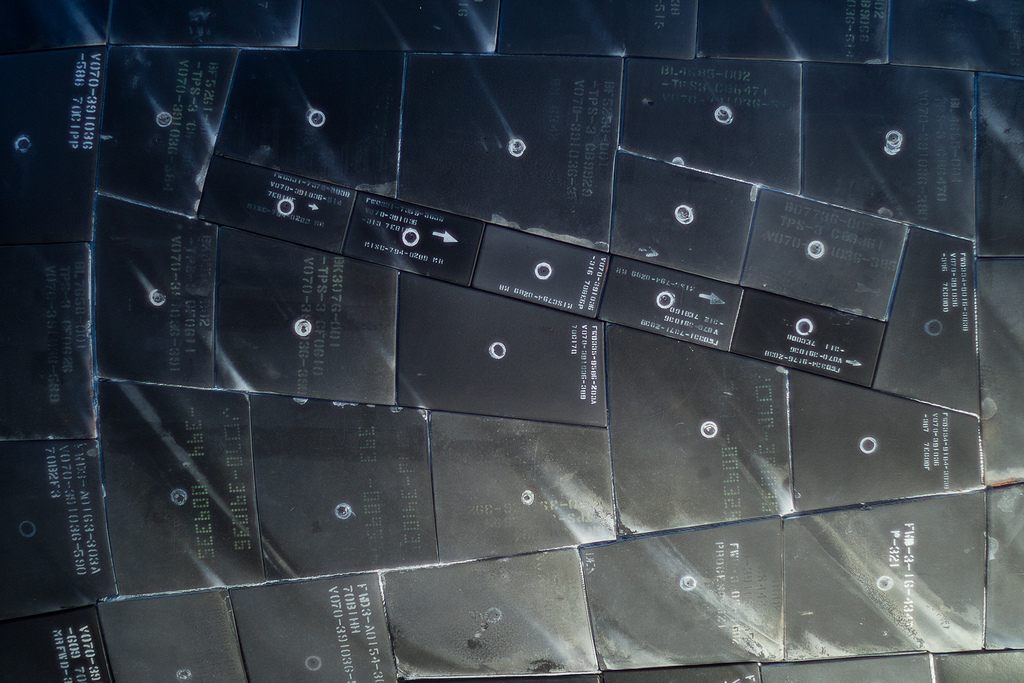

A close-up of the underside of the Discovery, covered in the heat-insulating tiles whose records have mysteriously disappeared. (Photo: NASA/Library of Congress)

In photographs, the Space Shuttle looks smooth. Midflight, against the black of space, its bright white surface seems almost enameled, like a big tooth spit into the solar system. But get closer, and the whole underside is actually covered in tiles—over 24,000 of them, molded from melted-down sand and stuck to each other with “space age glue.” When the shuttle still flew, each tile was responsible for protecting a fraction of it from the dangerous ravages of atmospheric heat.

NASA, in turn, was in charge of keeping track of the tiles. The agency developed a database in order to “document the condition of each tile, determine any necessary repairs or replacement, and generate work instructions.” Over the course of its 135 missions, the shuttle went through hundreds of thousands of tiles, each individually shaped, attached, and re-examined between launches. Such a mass of detailed records promises to be fascinating—the stories of each tile, when pieced together, would make up a kind of historical mosaic, an alternate illustration of the program as a whole.

The only problem? The database is nowhere to be found.

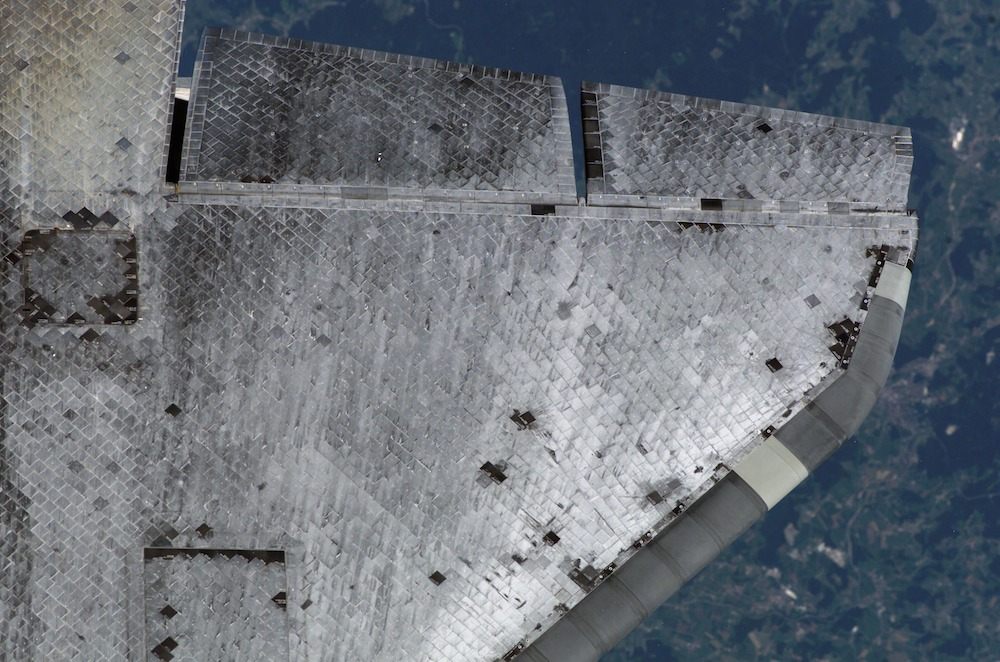

In space, no one can see your seams: Discovery orbits Earth in 1993. (Photo: NASA/Kennedy Space Center)

In space, no one can see your seams: Discovery orbits Earth in 1993. (Photo: NASA/Kennedy Space Center)

Until recently, it’s doubtful anyone was even looking for it. Enter Charlie Loyd. Last month, Loyd launched a website, shuttletiles.space, dedicated to finding the lost tile reports. He’s trying to piece together a forgotten part of history, and he needs the whole country’s help.

Loyd is an imagery specialist who spends his workdays making satellite maps more beautiful. He’s also an eloquent, passionate fan of space exploration, and of anything that, in his words, helps him to “grasp the spirit” of our various attempts at it. He forged an interest in the tiles a few years ago, after a close encounter with the shuttle Discovery at its current resting place, the Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia. He was wowed by the scrawl on the tiles—the carved-in serial numbers, rescue instructions, and other indications of “human drama” all over this larger-than-life machine.

“I knew roughly what to expect, but it was overwhelming,” Loyd recalled in an email. “It seemed appropriate and yet funny that every little part of the belly of this historic spacecraft had its own history as an object.”

The tiled tube hatch of the Discovery. The tile database supposedly contains hand-drawn records of all damage. (Photo: Charlie Loyd)

The tiled tube hatch of the Discovery. The tile database supposedly contains hand-drawn records of all damage. (Photo: Charlie Loyd)

He dug a little deeper, and found this history spanned decades and demographics. Beyond their major plot lines—tile problems delayed mission after mission, and the 2003 Columbia disaster was partially caused by a failure of the thermal protection system as a whole—the tiles played a role in more day-to-day stories. Earthbound workers nicknamed the shuttle “the flying brickyard,” and astronauts flipped it belly-up to do test repairs in space. Since the shuttle’s retirement, NASA has donated leftover tiles to schools and universities, and former technicians have been arrested for selling them.

Perhaps most surprisingly, “a lot of the first tiles were applied by college students on summer vacation,” Loyd says. This kind of detail raises questions that keep him up at night: “How were they trained? How much were they paid? What was it like for them, subjectively?” With corners like this to tug on, Loyd says, “it’s impossible not to want to know more.”

A museum tour guide had implied that the truth was out there, in the form of “a binder for each tile with a picture and notes made after every flight,” says Loyd. “I assumed the database was probably a .zip of 500,000 scanned PDFs on nasa.gov or something.” But it wasn’t there.

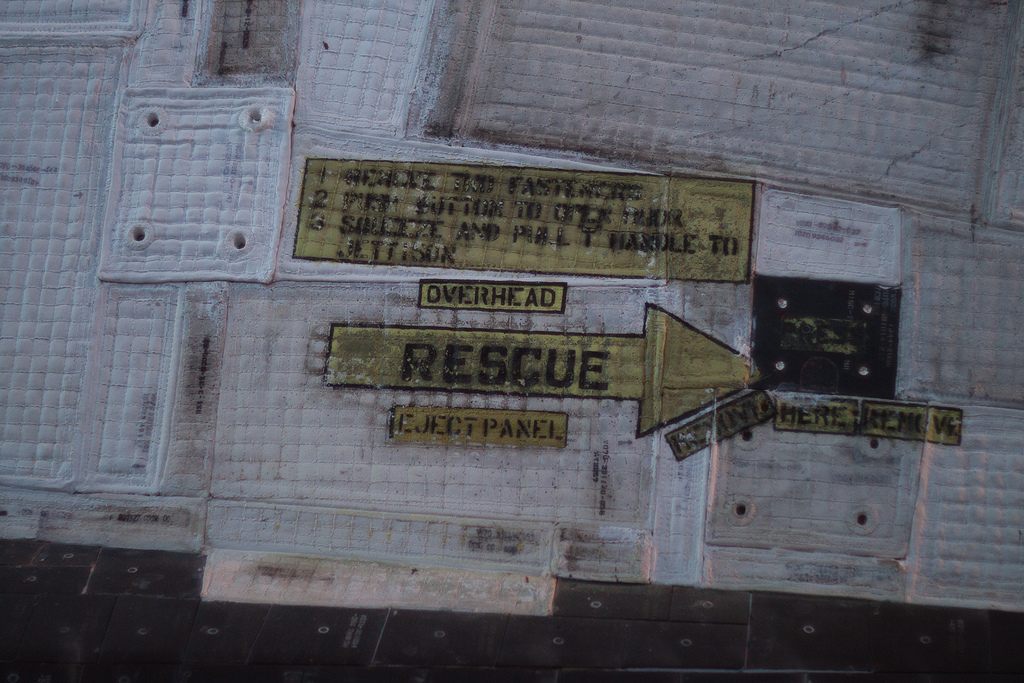

Scuffed-up rescue instructions, on a heat-protected surface that looks, Loyd says, ”like a claymation blanket.” (Photo: Charlie Loyd)

Scuffed-up rescue instructions, on a heat-protected surface that looks, Loyd says, ”like a claymation blanket.” (Photo: Charlie Loyd)

So Loyd began launching probes into the unknown. Boeing, who helped develop the tiles, couldn’t tell him anything; neither could government officials. FOIA requests came up empty, too.

The website is Loyd’s latest and most exhaustive attempt to locate the tiles, and his first time directly asking the public for help—a strategic gesture, but also one that reflects how he views his subject. The shuttle, of all spacecrafts, has “an iconic clarity, a mythopoetic power,” he says. It was the first project, after the military-driven Space Race, that “said the American space program is for Americans. Nothing can replace that… the Shuttle made space flight normal, but kept it special.”

He hopes knowing more about the tiles will shed more light on this tension, just as other artifacts, like patched-up space jackets and bluntly captioned Soviet rescue capsules, throw it into relief.

Of course, the fact that these records are part of the past points out another contradiction. Loyd only saw the tiles in the first place because the space shuttle is now grounded, the result of shifting national priorities. “We have one of the most wonderful institutions in history, tremendously popular with taxpayers, but we treat it like we’re ashamed of it,” Loyd says of NASA. If we aren’t willing to fund its future accomplishments, caring about its past ones is the least we can do.

The underside of the Discovery’s starboard wing, being inspected for damages as it floats above Earth. (Photo: NASA/WikiCommons)

The underside of the Discovery’s starboard wing, being inspected for damages as it floats above Earth. (Photo: NASA/WikiCommons)

He feels “excited but patient” about this new chapter of the search. “If it’s only available on paper, it might take a huge crowdsourced effort to get it scanned and typed up,” he says. “Or hypothetically, if some paranoid bureaucrat marked the tile data as secret during the Cold War, it might take several decades to get it fully declassified.”

Loyd himself is not a conspiracy theorist (an accusation he addresses on a website subpage, “Are you a conspiracy theorist?”). He’s not looking for trade secrets or cover-ups. He’s just hoping to pay proper attention to an overlooked piece of American history—a piece that happens to involve many, many pieces.

If nothing else, he hopes his quest reminds people that, even though the shuttle has docked for good, some types of exploration are still possible. “This project is about certain hardware maintenance records,” he says, “but it’s also about remembering that there’s treasure everywhere.”

Challenger orbits Earth in 1983. (Photo: NASA/WikiCommons)

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to cara@atlasobscura.com.

Update, 7/8: The original version of this article said that the tiles themselves were responsible for the Columbia disaster—it was actually damage to several Reinforced Carbon-Carbon panels, a different part of the thermal protection system. Thanks to Will Rope for the correction, and we regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook