The Restaurant Reconstructing Recipes That Died With the Ottoman Empire

Eating like a sultan takes lots of detective work.

Here’s a basic shopping list if you’re chef to the Ottoman sultan: The dried glands of a musk deer, a bushel of violets, ambergris from whale bellies, and handfuls of desert-harvested frankincense.

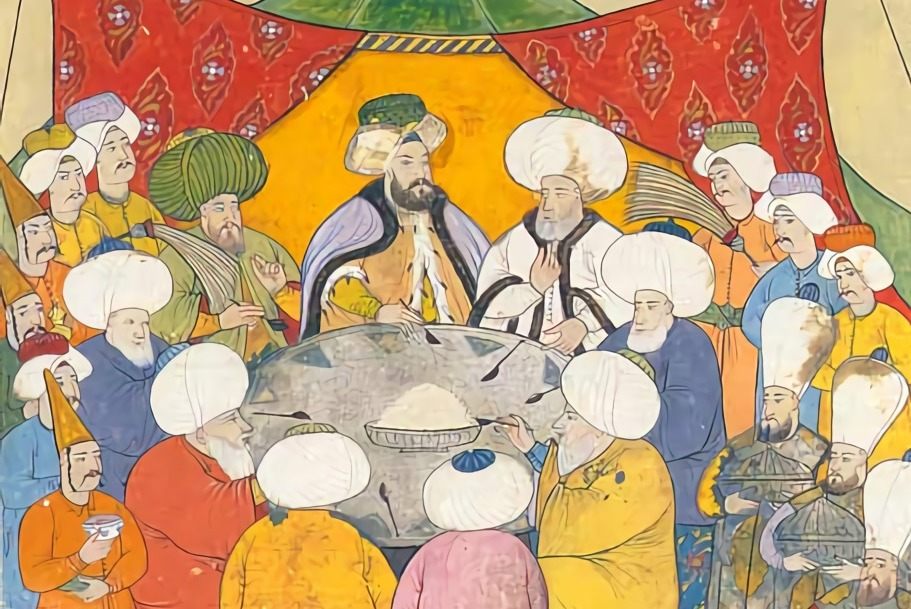

The Ottoman Empire once extended from Istanbul all the way to Arabian deserts and Caucasian glaciers. Sultans craved delicacies sourced from every corner of their lands, and palace chefs wove those far-flung ingredients into a distinctive cuisine. It must have seemed like both their power and their cuisine would prove eternal. After all, the Ottoman dynasty did endure for more than 600 years. But when the empire fell after the First World War, palace cuisine disappeared as well.

A few miles away from Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace, once home to many Ottoman sultans, Asitane Restaurant is on a quest to bring that palace cuisine back. According to owner Batur Durmay, Turkish cooking didn’t have much cachet when his parents opened the family restaurant in 1991. “At that time,” says Durmay, “if you wanted to go out for a nice meal you ate French or Italian food.”

The Durmay family decided that Istanbul deserved a restaurant worthy of the city’s imperial past. They founded one themselves, calling it Asitane as a tribute to one of Istanbul’s many historic names. “Since they had no idea where to start,” says Durmay, “they hired researchers to figure out how to make classical Ottoman dishes.”

There was more to the quest than digging up old cookbooks. In her recent book, Bountiful Empire: A History of Ottoman Cuisine, historian Priscilla Mary Isin describes a closed guild system of cooks during the Ottoman Empire that guarded culinary secrets and forbade members from writing recipes down. To make matters worse for these food detectives, what was recorded is now illegible to almost everyone. While modern-day Turkish is written in the Latin alphabet, Ottoman Turkish was written in Arabic script. Just decrypting a shopping list from the Ottoman era requires a scholar.

With few recipes to guide them, Durmay’s family relied on researchers and academics to search for menus detailing historic feasts held by sultans, records of food purchased for palace kitchens, and written accounts by foreign travelers. Isin, who used similar sources when researching her book, writes that even people who wouldn’t document their meals at home elaborated on food they ate on the road. One traveler, the French chef Alexis Soyer, secured an invitation to an elegant garden banquet held in 1856. The meal featured two entire sheep and two entire lambs, their grilled entrails, and 31 other dishes that went from stuffed vegetables to a sequence of desserts. “Apicius would have gone to Turkey to dine,” wrote Soyer, evoking the ancient world’s most famous gourmand, “had he known such delicacies were to be obtained there.”

In some cases, Durmay explained, these diverse sources proved invaluable for cross-referencing their findings. One strategy was to take a list of the dishes served at a notable feast, check those items against the week’s palace receipts, and look for descriptions from anyone who’d attended the feast. The result of this culinary sleuthing is a collection of hundreds of recipes that the kitchen rotates with the changing seasons. Now, nearly every dish on the menu is inspired by findings from the Ottoman era. On a recent afternoon in Istanbul, I ate an almond soup brightened by vivid pomegranate seeds based on an Ottoman dish recorded in 1539. Next, a grainy scoop of crushed chickpeas arrived alongside bread rolls made with gum mastic. Durmay believes that the chickpea spread, created using records from 1469, is the ancestor of hummus. Enriched with cinnamon, pine nuts, and currants, it’s an aromatic version that balances sweet and savory flavors.

Then I tasted fried beef and lamb liver rissoles from the 17th century, swabbing each bite in a syrupy relish of red onions and pomegranate molasses. Next, I cracked open a whisper-thin bread crust to reveal roasted goose and almond pilaf, and sliced into a roasted quince stuffed with beef, lamb, currants, and pine nuts. Voicing a complaint that any sultan’s chef might have sympathized with, Durmay noted the difficulty of sourcing large, unblemished quince for this latter dish, which appears on the menu each winter. Isin writes that the sultans made it illegal to sell luxury foods in Istanbul before the palace was fully supplied. Without the powers of an autocrat, Durmay just pays fruit vendors extra to reserve him the most perfect specimens.

After that hard-earned quince was cleared away, the meal concluded with almond halva and sembuse, a fried turnover from 1650 filled with pounded almonds, walnuts, and musk. The perfumed sembuse, which requires painstaking preparation, helps explain why Ottoman palace cuisine disappeared when the empire fell.

In her book, Isin writes that chefs in the sultan’s palace were highly paid and highly specialized. To produce the intricate, multi-step dishes that were so prized, a chef might limit themselves to the art of kebabs, or perhaps stick to pilaf, preserves, dolma, or desserts. The knowledge of how to prepare each dish was passed from cook to cook, with no single member of the palace kitchen responsible for safeguarding or recording the cuisine.

The early years of the 20th century brought enormous turbulence to the Ottoman Empire, when the Balkan Wars were quickly followed by the First World War and the Turkish War of Independence. Those conflicts destabilized the empire and emptied kitchens. Isin writes that cooks were drafted into the army or simply left unemployed, breaking the chain of apprenticeship and teaching that had developed palace cuisine into a deeply specialized art.

The changes that swept through Ottoman kitchens went beyond recipes, ingredients, and feasts. Food was political, and the politics of Istanbul were transformed by the rise of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who founded the modern Turkish state in 1923 with a firm commitment to secularism and modernization. “The Ottoman period was cast as a time of backwardness and conservatism,” writes Isin, “and traditional culture was often blackened with the same brush.” She notes that cooking schools gave up local foods in favor of French cuisine, and that Turkish dishes disappeared from upscale restaurants and pastry shops. Even when Durmay’s parents first opened Asitane in 1991, he says that many considered the idea of elevating Ottoman culture unusual.

But Turkey has changed in the nearly three decades since the restaurant was founded, and the Ottomans are back. Now, the former empire’s name is emblazoned on everything from kebab shops to carpet stores. It’s a symptom of a broader shift in Turkish culture. Under President Recep Erdogan, a political and cultural trend sometimes called Neo-Ottomanism has stoked nostalgia for the Ottoman Empire’s power and piety. It is a celebration of the past, but it also evokes a time when Istanbul’s influence stretched far beyond the borders of modern-day Turkey.

When I asked Durmay to choose a favorite Ottoman feast, though, it wasn’t a royal banquet from the empire’s apex. Instead, he settled on a meal that was held in 1898 inside Yildiz Palace as a celebration of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s visit to Istanbul. Then the German Emperor and the King of Prussia, Wilhelm had a great, swooping mustache and military bearing; he liked to pose for portraits in the pointed helmet of the Prussian army. His Ottoman counterpart was Sultan Abdülhamid II, who preferred an elegant fez.

To honor the meeting of two great empires, the menu blended European dishes with Ottoman specialties. Dishes included venison pâté, two kinds of börek, a type of filled savory pastry, then pheasant kebab, quail, and roasted legs of lamb. After rice pilaf was whisked from the table, servers laid down platters of turkey, mushrooms, and white truffles. The guests must have been full to bursting as the meal concluded with sweet almond butter and ice cream. They might not have known as they lingered over dessert and conversation, but that night’s invitees were dining in the twilight of an era.

Wilhelm II was the last of his kind. After him there would be no more German emperors, no more kings of Prussia. His wasn’t the only empire coming to an end. Eleven years after the tables were cleared, Sultan Abdülhamid II was deposed, leaving hundreds of palace chefs out of a job. When they packed up their tools, they left for restaurants, joined the army, or simply abandoned Istanbul to look for work in the provinces. The knowledge they took with them would never return to the palace kitchens of Istanbul. Much was lost forever. But enough of their shopping lists, menus, and stories were saved to tantalize historians—and to serve as inspiration for Istanbul’s food detectives.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook