Remembering When Only Barbarians Drank Milk

“Butter eater” was once a terrible insult.

This article is adapted from Milk! A 10,000-Year Food Fracas by Mark Kurlansky.

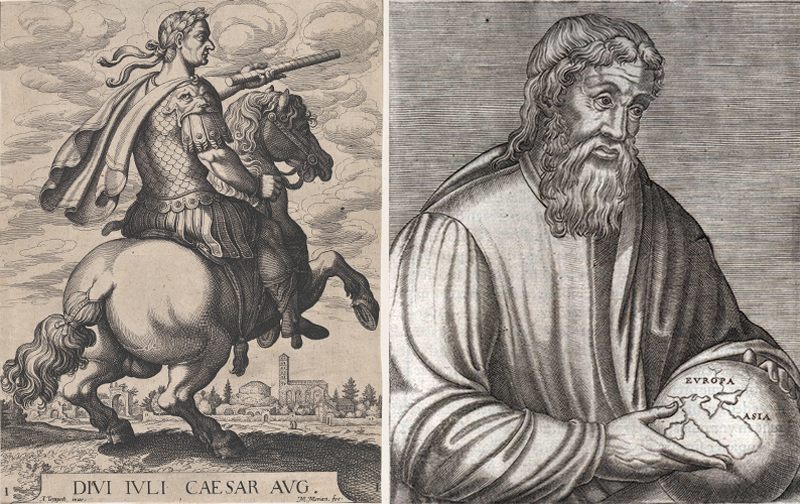

During a visit to conquered Britain, Julius Caesar was appalled by how much milk the northerners consumed. Strabo, a philosopher, geographer, and historian of Ancient Rome, disparaged the Celts for excessive milk drinking. And Tacitus, a Roman senator and historian, described the German diet as crude and tasteless by singling out their fondness for “curdled milk.”

The Romans often commented on the inferiority of other cultures, and they took excessive milk drinking as evidence of barbarism. Similarly, butter was a useful ointment for burns; it was not a suitable food. As Pliny the Elder bluntly put it, butter is “the choicest food among barbarian tribes.”

Ancient Romans were not alone in looking down on butter and milk. In Greece, the word “butter” was not spoken kindly. The Greeks called it boutyros, cow curds, and as sheep and goat people, they regarded those who kept cows and made butter as an alien lot. The Thracians, the people who lived to the north of Greece, ancestors of the Bulgarians and others, ate butter. Greeks contemptuously referred to them as “butter eaters.”

For centuries, this was the norm in many parts of the world: People who ate butter and drank milk were uncivilized outsiders.

Curiously, the Greco-Roman disdain for dairy stopped short at cheese. In Rome, cheese was eaten by both the rich and the poor. A considerable variety of hard, soft, and smoked cheeses were produced in the city, and others were imported from around the empire. Smoked goat’s-milk cheese from Velabrum, the valley by the Forum that runs up to Capitoline Hill, one of the seven hills of Rome, was especially popular—part of a general fondness for smoking foods. Cheeses were often given as gifts, and they were a standard breakfast food, along with olives, eggs, bread, honey, and sometimes leftovers from the night before.

But Mediterranean people had little need for butter. They already had olive oil, which is less prone to spoilage, heats to much higher temperatures without burning, and was and is regarded as more healthful. Even now in North Africa, most of Greece, Mediterranean France, Spain, and most—but certainly not all—of Italy, olive oil dominates and butter is rarely used. An omelet may be made with butter in Greece today, but until recently, even that was made with olive oil.

Climate, then, determined the poor status of butter and milk. Because they spoiled quickly in the climate of southern Europe and kept far better in northern Europe, northerners used far more milk. Germanic people were avid butter eaters and were said to have perfected salted butter. The Celts, who settled down in good dairying spots such as Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, also became known for their butter. Milk was so important to the “barbarians” that a dry cow was considered a family crisis.

This led southern classical cultures, which were already contemptuous of northerners, to take the greater consumption of dairy as evidence of their barbarian nature. To hear the Romans tell it, the barbarians to their north were swilling milk by the mugful. (In actuality, they were consuming milk conservatively; a cow was an expensive animal to maintain.)

Differences in climate made butter and milk a mark of otherness—unlike cheese which kept better in warmer climes. Since the presence of large, powerful cities and cultures in the far north is a relatively modern development, this linked any non-cheese dairy with inferior (or at least less powerful) groups.

Drinking milk wasn’t unknown in places such as Ancient Rome. But for similar reasons, it was linked with the country and lower classes. Until the age of refrigeration, very little fresh drinking milk was consumed in the Middle East. In Rome, due to the inevitability of spoilage, and because fresh milk was available only on farms, it was consumed mostly by the farmers’ children and by peasants who lived nearby, often with salted or sweetened bread. This led to fresh milk’s being widely regarded as a food of low status. Drinking milk was something that only crude, uneducated rural people did and was rare among adults of all social classes.

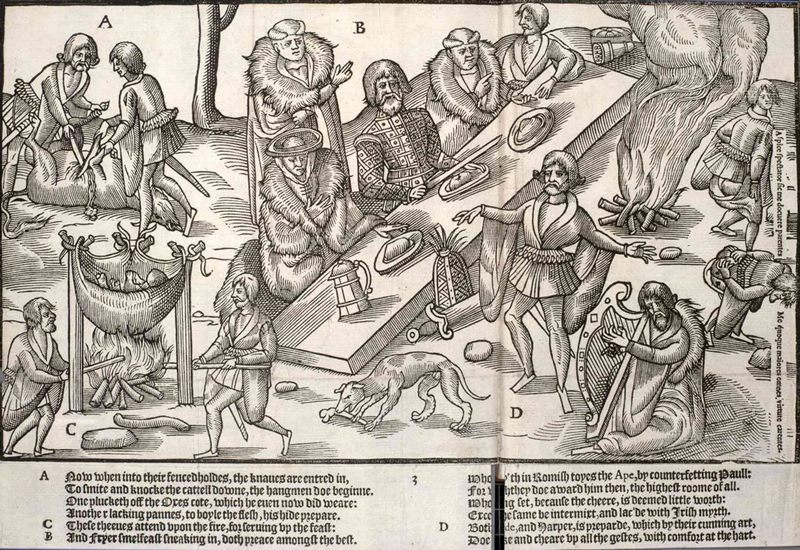

The link between milk, butter, and rural farmers ensured that even after Rome fell (to milk-swilling barbarians), dairy remained uncouth. The English, whose model for imperialism was the Romans, sneered at what they thought was the barbaric overuse of butter by the Irish. Fynes Moryson, secretary to the viceroy, who spent much time in Ireland in the reign of Elizabeth I, reported that the Irish “swallow whole lumps of filthy butter.” And southern Europe never lost its sense of superiority over its neighbors, still considering them to be milk-swilling barbarians.

If anyone can take credit for raising milk and butter up to respectability, it is the dairy-crazed Dutch.

In the country’s early years, the Dutch were singled out as a crude and comic people endlessly engorged on milk, butter, and cheese. Even the Flemish laughed at them, calling them kaaskoppen, or “cheese heads.” Northerners, too, belittled the Dutch for their dairy habits. One English pamphlet said, “A Dutchman is a lusty, fat, two legged cheese-worm.”

Insults aside, it wasn’t exaggeration. The upper classes prided themselves on setting their tables with several types of butter. The Dutch enjoyed whey or buttermilk with breakfast—even in the poorhouses, breakfast was buttermilk and bread—and butter was used wherever possible. A traditional meat stew, hutsepot, used butter too.

The Dutch navy, which in the 16th century was becoming a formidable force, issued to each sailor a weekly ration of half a pound of cheese, half a pound of butter, and a five-pound loaf of bread. The historian Simon Schama calculated that a Dutch ship with a crew of 100 in 1636 would need among their provisions 450 pounds of cheese and one and a quarter tons of butter.

An ample supply of cheese and butter was the right of every Dutchman. They believed that dairy food was an essential part of a good diet, and artists from the celebrated Dutch school of still-life painting often included cheeses in their compositions. The Dutch made many cheeses and had an effective distribution system, with numerous urban centers featuring cheese markets.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Dutch became skilled at reclaiming land from the sea by building dykes and creating polders, drained patches of reclaimed seabed. This led to dramatic improvements in cattle breeding and land maintenance. Farmers began having tremendous success crossbreeding livestock to develop cows that produced more milk—between the mid-16th and mid-17th centuries, the value of a Dutch cow quadrupled. The Dutch were starting to understand what best to feed cattle, and how best to cultivate pastureland. Soon, their cows were producing more than twice the yield of cows in neighboring countries.

Though at first unnoticed, a huge shift occurred in the European perception of the Dutch. Their country, which had broken off from Spanish rule in the 1590s, was rapidly changing from a former lowly possession of the Holy Roman Empire to an independent republic displaying a genius in art, science, and engineering. Seemingly overnight, the Netherlands became a global trading empire and leading maritime and economic power of the world. Suddenly, the cheese heads were considered brilliant.

All over Europe there were discussions and writings about what made the Dutch such geniuses. And those having these discussions often freely admitted that they had once thought of the Dutch as idiots who just drank milk and ate cheese. The Europeans also started recognizing that there was genius in Dutch dairy farms—in their better pastures, better cows, and ability to farm below-sea-level land. Dutch dairying, too, was now considered brilliant.

After the cheeseheads proved themselves geniuses—and established a widely emulated, global empire—the main bastion of anti-dairy sentiment was East Asia. Japanese Buddhists avoided dairy products and looked down on Westerners, who they thought consumed too much dairy. They claimed they could smell it on them, and even into the 20th century used the pejorative term Batā dasaku, or “butter stinker,” for a Westerner.

Similar sentiments existed in China, where the consumption of dairy has been so rare that historically, many have assumed that the Chinese as a race were lactose-intolerant. This contrasted with their neighbors, the Mongols, who drank mare milk and traveled with dried cheese curds.

But this is changing. China has become the world’s third-largest milk producer, and today, almost 40 percent of Chinese drink milk, the highest percentage in Chinese history. The new and growing upper class tends to crave everything Western, and dairy is Western. Ice cream is popular, and yogurt parlors are in, too.

Milk has been debated for at least the past 10,000 years. It was the first food to find its way into a modern scientific laboratory, and it’s the most regulated of all foods. People have argued over the importance of breastfeeding, the healthful versus unhealthful qualities of milk, farming practices, animal rights, raw versus pasteurized milk, the safety of raw milk cheese, and more.

But one argument that seems to have been finally set to rest is that milk and butter are no longer just for barbarians.

This article is adapted from Milk! A 10,000-Year Food Fracas by Mark Kurlansky, available now wherever books are sold.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook