Everything You Thought You Knew About ‘Hobo Code’ Is Wrong

Rail riders past and present leave messages for each other, but not the ones you’ve probably heard about.

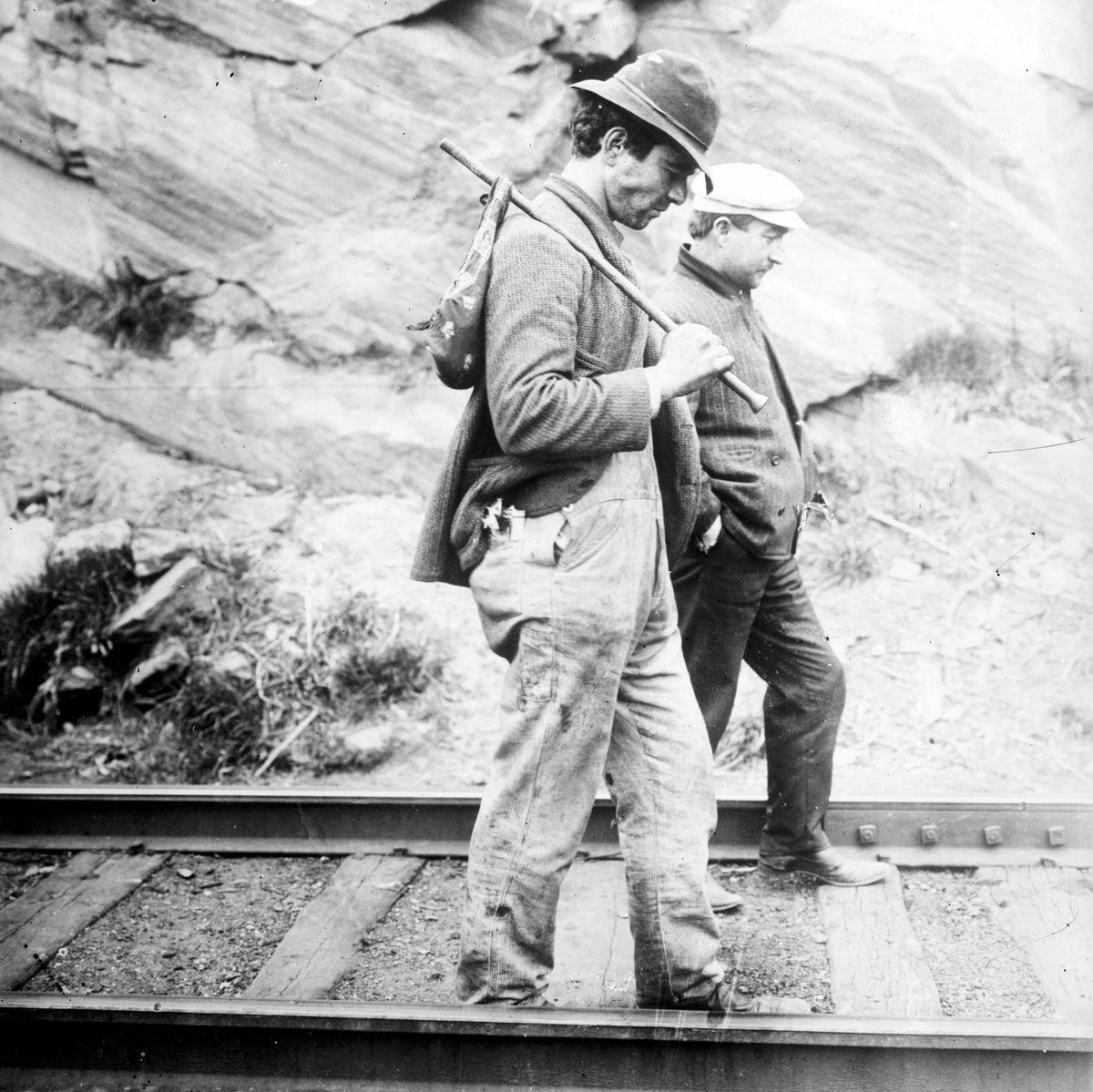

Connecticut Shorty caught her first ride in the porch of a grainer—the slender, metal cutout on a grain-filled train car—traveling about 200 miles across Northern California, from Dunsmuir to Roseville. It was 1993, and Shorty, then 51, was learning how to hop freight trains from a man known as Road Hog USA. He was a hobo, part of an American tradition that emerged after the Civil War: transient laborers who rode the rails and found short-term work along the way.

Shorty, diminutive in stature but enormous in charisma, was eager to experience the freedom and intensity of the hobo lifestyle for herself, even though she was already familiar with the culture. Her father, a legendary hobo known as Connecticut Slim, rode steam engines for 44 years. Her great-uncle Louis was another steam-era hobo who hopped from town to town, looking for work and opportunity.

One thing Shorty already knew was that hoboes left distinctive messages for each other in code. “This way other rail riders who might want to locate them would have an idea when they passed through and where they were headed,” she says.

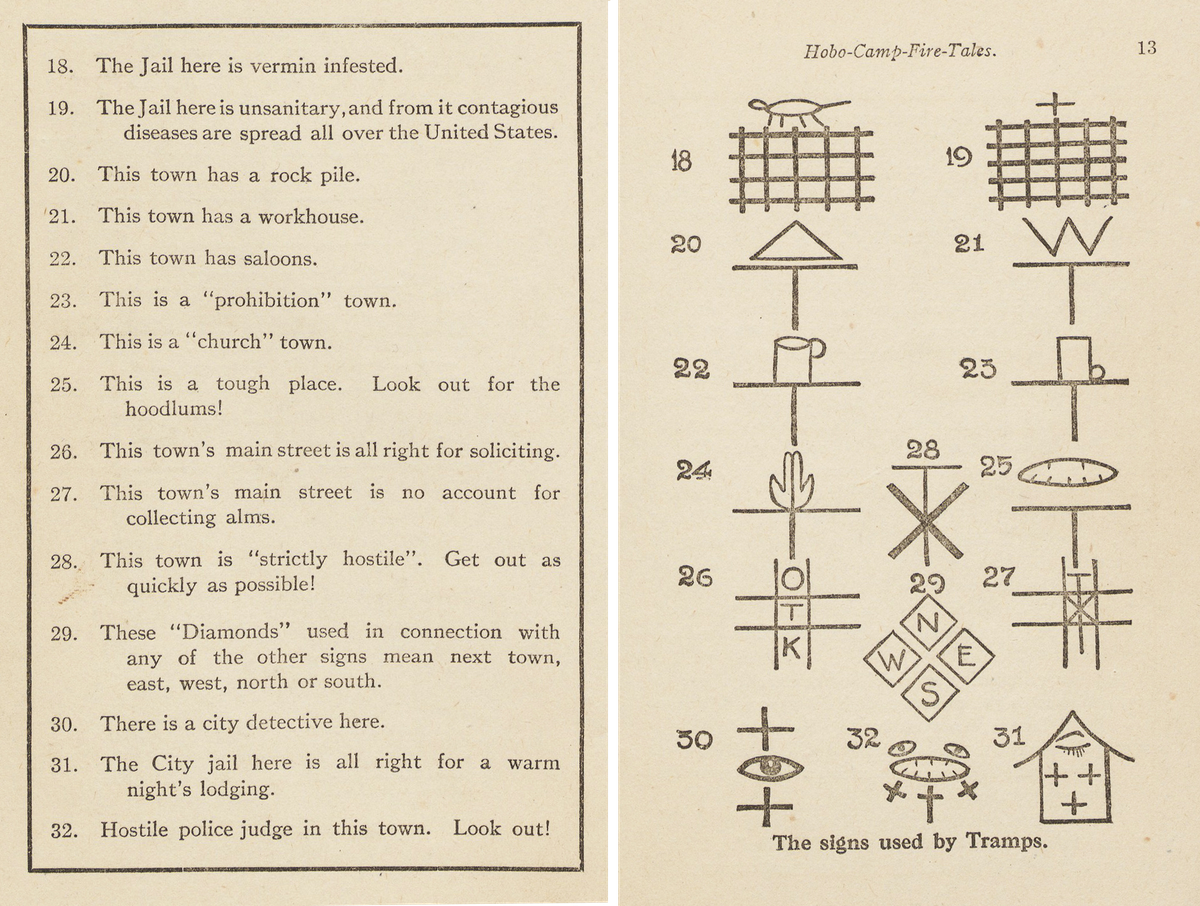

But those messages might not be the hobo code you’ve heard about. Popularized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, hobo code supposedly consisted of distinctive symbols to communicate vital information. They alerted other transient workers to trouble, such as an aggressive dog or hostile police force, but could also point the way to clean water or a hot meal. Three lines might mean a good place to camp; an upside-down triangle signaled a spoiled road; a cat was code for a kind woman.

It’s the kind of thing one might find drawn on wooden posts, written under bridges, or carved into tree trunks. But more often the code was impermanent, scrawled with chalk or coal, even etched into the dirt.

My grandfather shoveled coal for steam engines on the B&O Railroad in Indiana from the 1930s until 1950, a time when it was common for hoboes to hop onto boxcars and ride the rails from one town to the next. I grew up hearing stories about the drawings that led hoboes to my grandparents’ house, which was a safe spot to get a sandwich or a slice of pie. In these family stories, hobo code was established as fact. But did hoboes actually leave secret messages like these?

It’s a question Charlie Wray of Salt Lake City has also been trying to answer. Wray, along with his father Mike, founded the Historic Graffiti Society, an organization that preserves and records historical markings with a focus on those from the hobo era. For the past several years, they’ve documented original markings across the United States in abandoned train stations, under bridges, and inside tunnels. “There’s always been an American fascination with hoboes,” Charlie Wray says. “People like to fantasize about the freedom that comes with it.”

Newspaper articles as far back as 1870 mentioned the possibility of “tramp signs” and “hobo hieroglyphics.” As the code gained popularity, it popped up in comic strips and advertisements—and was even used in anti-hobo campaigns. A 1912 article from The St. Louis Star-Times reported that Cincinnati police officers chalked the symbol for “unwelcome” throughout the city in an effort to scare away hoboes.

Yet the Historic Graffiti Society has found no concrete evidence that hobo code existed. Wray says decades-old claims in newspaper articles are unsubstantiated. The symbols said to be used by hoboes are often contradictory. And while there are photographs of hobo signs taken in the early 1900s, Wray adds, those were staged by newspapers.

“Modern Americans are convinced that hobo signs are authentic history, but the evidence against it definitely outweighs the evidence for it,” Wray says.

The lore of hobo code seems to stem from Leon Ray Livingston, better known as “A-No. 1,” arguably the most famous hobo in the late 19th century. A-No. 1 wrote 12 books packed with wildly entertaining but exaggerated stories that established the mythology of hoboes. One of Livingston’s books contained a homemade chart of “signs used by tramps,” and such stories increased his notoriety.

Other contemporary firsthand narratives never mentioned hobo signs or a secret code. That includes the detailed accounts written by Jack London about his time on the rails.

Hoboes did leave marks, but instead of code, they were monikers: markings with the hobo’s nickname, the date, and an indication of direction of travel. Many oral histories and written accounts describe monikers, including London’s memoir, The Road: “Water-tanks are tramp directories. Not all in idle wantonness do tramps carve their monicas (sic), dates, and courses.”

There was also Tex, King of Tramps, who began traveling around 1915 and claimed to have stenciled his bold moniker—“a traveling man’s cryptic mark” according to The Billings Gazette—on more than 7,300 structures across the country.

These are the type of markings that Connecticut Shorty knows. “Some rail-riding friends have left messages under bridges, leaving their moniker, the date, and arrow pointing to the direction they were heading,” she says.

The Historic Graffiti Society has documented more than 1,000 pieces of hobo graffiti, including hundreds of monikers and some chalk marks that go back more than 100 years. They have not yet found any hobo code. “I would love to be proven wrong,” Wray says. “So I keep looking.”

For others, however, the lack of evidence is not conclusive. “I tend to believe something existed,” says Jennifer Wilcox, curator at Maryland’s National Cryptologic Museum. “Maybe it was not to the extent that scholars would like, but it seems like, if it was just made up, hobo code would have died out a long time ago.”

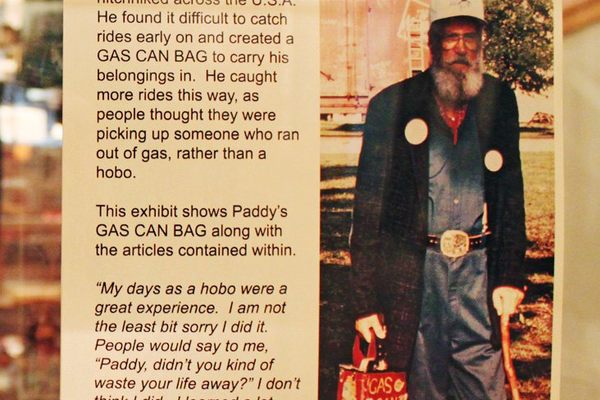

Wilcox created a hobo code exhibit, “Looking for a Sign: Hobo Communication in the Depression,” based on historical research pulled from newspaper articles, interviews with modern-day hoboes, and information from the Hobo Museum in Britt, Iowa. The exhibit opened in 2007 and was intended to run two years. However, due to its popularity, it remained open until 2020. The exhibit included a game based on a model train layout with symbols painted throughout the miniature town; visitors were asked to decipher the hidden code.

When planning the exhibit, Wilcox says she drew upon stories about hobo code from her mother, similar to the yarns spun by my grandfather and many others of their era. The sheer number of nearly identical recollections about the symbols could be interpreted as proof the code was real. But the truth is not so clear-cut.

During periods of economic turmoil, particularly during and after the Great Depression, millions of migratory laborers took to the hobo circuit to find work. If someone lived near a train station, within proximity of a hobo camp, or along the route to the local Salvation Army, odds were good that a hobo would eventually stop by, no code necessary.

“Not to say the stories are totally false, but it’s much more likely that these houses were called at by chance,” Wray says. Many people probably assumed there was a code, he adds, “because hoboes kept showing up.”

Firsthand accounts from hoboes do mention another form of communication: word of mouth. “That was the real language of the road,” Wray says. “It was efficient and effective. There was no need for signs or symbols.”

This is true of modern rail riders, too. Slender and sinewy Sol Jacobs, clad in overalls, spent a decade hopping trains and playing banjo all over the country before settling in Pueblo, Colorado, to raise a family. He learned critical information about trains from more experienced riders, then passed it forward. He flashes the words “RIDE FREE,” inked across his knuckles. “People see the tattoos and say they want to do it, so I tell them how,” he says.

There are also crew change guides, closely-guarded documents detailing where to find a hop-out point, how to navigate specific train yards, best practices for avoiding the “bulls” (security guards), and more. Long circulated in handwritten or printed form, some crew change guides now exist as digital files, but authentic versions are still kept within the community.

When Jacobs traveled, he used a moniker, and says most riders still do, one holdover from the hobo era. His is simple: SOL, all capital letters, usually painted in orange or red. “It’s because I’m no longer Solamon when I’m on the road. I’m SOL, shit out of luck,” he says with a laugh.

It’s important to mark one’s territory, he adds, maybe even more so when you’re there one day and gone the next. “It’s not so much to let people know where you’re going,” Jacobs says. “It’s to show you exist.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook