How 19th-Century Zombie Dogs Revealed the Workings of the Brain

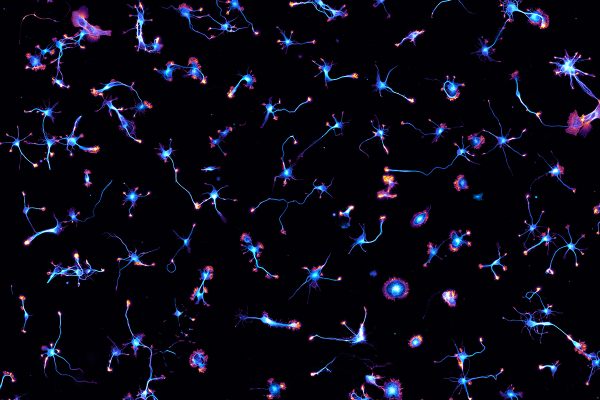

A dog’s brain (Photo: katja/Pixabay)

This is part one of a three-part series on decapitation. The story below contains some disturbing treatment of animals, including dogs and monkeys, so if that sort of thing bothers you, beware.

Freidrich Leopold Goltz spent much of his time, in the 1870s, decapitating frogs. Goltz was a physiologist, and he would cut out both of the frogs’ cerebral hemispheres, leaving just a small part of the neural center intact. And then he would see what they could still do.

A brainless frog could do a lot, it turned out. Put the frog on its back, and it would flip right side up. Put it in water, and it would swim. Poke it, and it would hop away. It could even croak, if its back was stroked. It was even possible to keep a frog alive, even with its head cut off entirely, if a bit of brain was left behind.

These frogs, though, were not entirely themselves. “The brainless frog,” wrote David Ferrier, a rival neurophysiologist, who summarized Goltz’s observations, “will become converted into a mummy. All spontaneous action is annihilated…and it exhibits no fear. Surrounded by plenty it will die of starvation.”

At the time that Goltz and Ferrier were working, the brain was little understood, and they aimed to discover how it worked. The two scientists were on opposite sides of a major debate in neurology at the time: do certain areas of the brain have particular functions? Or is it one giant lump of unspecialized neural tissue?

The only way for them to answer the question was through gruesome experimentation, work that was wildly controversial even in its time.

This question had its origins in phrenology but by the late 1880s, scientists had abandoned the idea that there might be brain centers for capacities like emotion, suavity and verbal memory. Instead, they were focused on mapping the sensory-motor functions of the brain. Instead of a place that controlled language, in other words, they were looking for places that controlled mouth and hand movements. Frogs were just one research subject: these scientists and other like them cut out the brains of guinea pigs, pigeons, rabbits, cats, dogs and monkeys, in order to try to understand if damage to certain parts of the brain caused particular deficits—and if they could fix them through surgery.

“It’s during that era that we have the modern experimental origins of the contemporary neurosciences,” says Larry S. McGrath, who teaches history at Wesleyan University. Goltz and Ferrier created these mummy frogs and zombie dogs to answer one big question: Can the mind be located in the brain? And if you think it can be located, then what do you mean by the mind?

Decerebrate cats were common research subjects and have been used in modern experiments, as well

The more complicated the organism, though, the harder it was to keep the animal alive after large chunks of its brain had been cut out. But the longer they could be kept alive, the more could be learned from the results of the operation. And no one was better than Goltz at keeping dogs alive after cutting their brains out.

His strategy for creating brainless zombie dogs involved multiple operations. First, he would destroy the right hemisphere of a dog’s brain. After the dog had recovered from that procedure, Goltz would start on the left hemisphere. That one, he took out in pieces. The first operation took out two brain lobes; two more followed, each destroying an addition lobe, until the dog was left with just a small nub.

Three of Goltz’s experimental dogs survived these operations. One lived for almost two months—57 days in total. Another made it three months, for a total of 92 days. And one dog recovered completely enough that after 18 months, he was doing well enough for a dog with no brain.

As with the brainless frogs, something was not quite right with Goltz’s zombie dogs. They didn’t sleep quite so soundly, and when they were disturbed, whether by hunger, prodding, or the need to pee, they would get up and run aimlessly for awhile, with its head down, before returning to resting state. And they never sought out food—left to their own devices, they would have starved.

But Goltz’s dogs also could do quite a lot, considering. They barked. They ate, when given food. They pooped. They responded to stimuli. They slept. This was enough to convince Goltz that the functions of the brain were not particularly localized—the animal could function well enough with just a portion. The brainless dogs might not have been the best or smartest or most fun dogs, but they were still dogs.

Members of the International Medical Congress of 1881 (Photo: Wellcome Trust/Wikimedia)

This is what Goltz argued, in 1881, at the International Medicine Congress in London, where thousands of doctors gathered together to discuss cutting edge medicine. One of the major events was a head-to-head between Goltz and Ferrier, who had been experimenting on monkeys and was convinced that Goltz was entirely wrong. Very specific parts of the brain, Ferrier believed, had very specific functions.

Goltz went first. He had brought two exhibits. The first was in a suitcase, which he placed on the lectern at the beginning of his talk. As he spoke, he opened it, to show what was inside—the skull of dog with only a tiny portion of the brain still there. Then, he brought out his most dramatic evidence: a living dog with almost no brain.

The dog, Goltz showed, could move like any dog—it could run and jump—and it responded to stimuli. It reacted to light and sound, and physical touch. There was a black-and-white flag placed on the floor, one observer reported, and the dog stepped around it. Goltz blew cigar smoke in the dog’s face, and it turned away. If Ferrier’s theory that motor functions were located in the brain’s cortex, long since gone in this dog, was correct, Goltz argued, the dog should not be able to do any of that.

Ferrier focused on monkeys, two in particular, with specific and, relative to Goltz’s excision, small parts of their brains removed. Both were healthy, except for their particular deficits. The small surgery had paralyzed one of the monkeys, just on one side. They other had been made completely deaf. Months after the surgery, no other part of the brain had stepped in to restore those functions.

After the two presentations, the assembled crowd was not ready to declare a winner. They wanted to see the monkeys. And so that afternoon, the scientists went to Ferrier’s lab to view the monkeys. Some were convinced just seeing them that Ferrier was right—by destroying a certain part of the brain, he had destroyed a particular capacity in each monkey. But some wanted further proof.

Ferrier and Goltz agreed: for all the effort they had put into keeping their research subjects alive, they could be sacrificed to determine which model was more correct. The monkey and the dog were both killed and their brains examined. That was when Ferrier won: the lesions he had made on the monkey’s brain were exactly as he’d said. But in the dog’s skull, the panel of experts found more brain than they were expecting. Different parts of the brain, they concluded, did have different, localized functions.

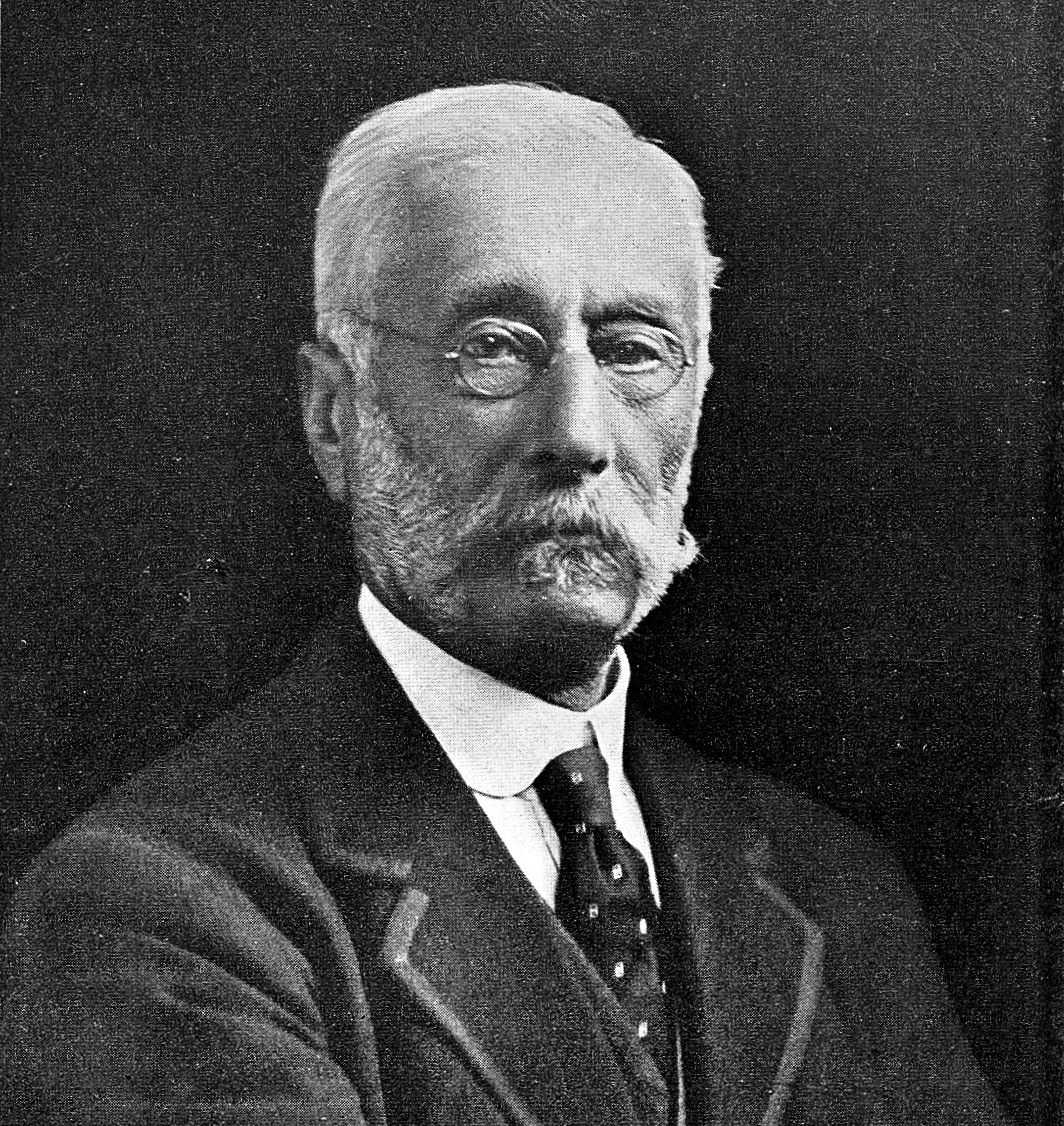

David Ferrier (Photo: Wellcome Trust/Wikimedia)

Ferrier paid for this victory. That November, he was investigated for violation of the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876.

As Goltz and Ferrier were ablating the brains of various animals, groups of activists were fighting back. In particular, the Victoria Street Society was against this sort of vivisection work, and they had pressed through the 1876, as well as a Royal Commission on Vivisection. When Ferrier had already been brought before the commission and when presented his monkey research in 1881, he again became a target of the animal cruelty activists.

The charge that Ferrier originally faced was that he did not have a license for the surgery on the monkeys. That charge was easy to answer: a colleague, Gerald Yeo, had performed the actual surgery and had the proper license. But the prosecution pressed on. The problem wasn’t just the lack of license, but that the monkeys had been kept alive after the surgery. Under the law, if animals would have experienced any pain once they came out from anesthesia, they were supposed to be euthanized before waking up.

But Ferrier was able to convince the judge, Sir James Ingham, that the monkeys had not experienced pain in their post-surgery lives—and that without keeping them alive, the entire point of the experiment would have been nullified. He was acquitted of the charges.

To be fair, the experiments that Ferrier and Goltz conducted contributed to the developed of neurosurgery and were far from the most gruesome conducted on dogs in the name of science. Within the next few decades, scientists in Russia would try the opposite gambit: instead of studying a dog’s brainless body, they would study a dog’s bodyless head (and Germans would try to transplant one dog’s head to another’s body).

This video is most likely a dramatization, but the research behind it is was real.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook