How a Fake Priest Smuggled Mezcal Out of Mexico

Mezcal bottles at a factory in Oaxaca. (Photo: ProtoplasmaKid/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

“Regalos para mis amigos y libros para los ninos.” John Rexer cringed as he heard the words come out of his mouth. “Gifts for my friends and books for the children,” he explained to the armed Guatemalan customs officer. He’d rehearsed the line a handful of times, enough to make it come out naturally if he was asked at the border what was in his six duffel bags. Now, in a crisp, white priest’s collar, he stood his over his bags and wondered if the cover went too far.

The officer asked him to open a bag. Rexer paused for a moment, and opened the nearest duffel to reveal reams of Mexican pornography that sat in layers above scores of illegal glass bottles. The contraband itself was tucked barely out of sight beneath the magazines. “Regalos para mis amigos y libros para los ninos.” The guard paused for a moment to drop his eyes, shook his head, and told Rexer he was free to enter the country. “Pasale, Padre. Pasale.”

The disguise worked, and while the officer was unimpressed with the conduct of the church, Rexer was allowed to pass without having the rest of his bags searched. He took his accomplice, a falling-down drunk jazz bass player with a waxed, pencil thin moustache and a southern drawl, by the collar and got back on the bus towards Antigua, Guatemala.

View from Cerro de la Cruz in Antigua, Guatemala. (Photo: Milosz_M/shutterstock.com)

Rexer’s bar, Café No Sé, is nestled amid the cobblestone streets and pastel facades of Antigua’s colonial architecture. The dimly lit watering hole shares the street with other bars, a hostel, a small internet cafe, and a door that swings open in the mornings to present a pair of local women who sell handmade tortillas and roasted chickens for lunch. The town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and tourist oasis in a country roiled by violence and corruption.

Café No Sé started as a place for wayward artists and expatriate musicians to gather on the road. It hosts live music nearly every night, drum beats and a barroom din wafting down the steps onto the street. The mezcal that’s now synonymous with the place came later, as did the bar’s hidden parlor room for drinking it.

A taste for the smoky Mexican spirit made from the agave plant took hold slowly in Antigua. The clear or amber-hued spirit is fiery at first sip, as if tequila, scotch, and your grandfather’s war stories are all mixing at the back of your throat. It’s an acquired taste. “Drink it slowly, my friend,” Rexer advises as he pushes a small pour across the bar.

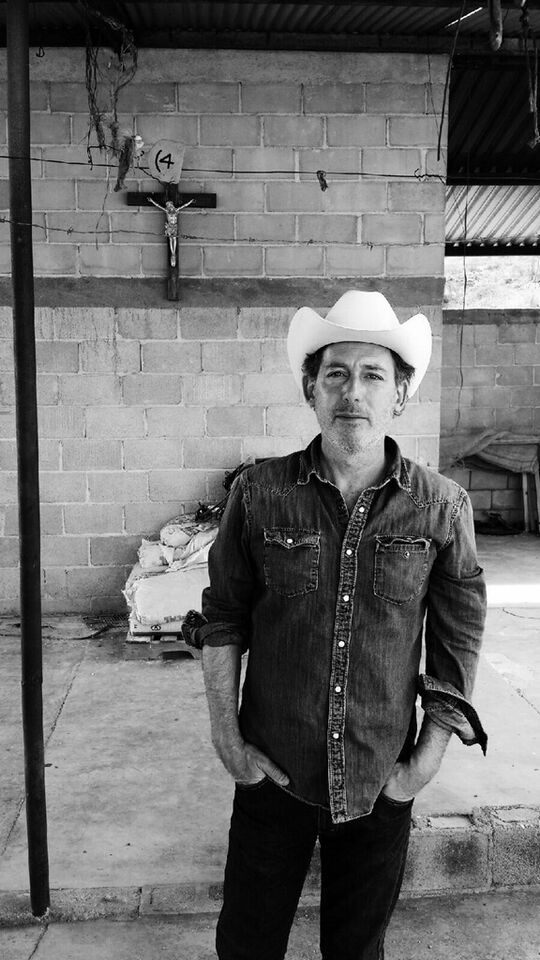

John Rexer found his way around mezcal over a decade of riding buses through southern Mexico. (Photo: Omar Alonso)

In the early days Rexer found himself ferrying a few bottles at a time across the border to supply his nascent bar. He’d picked up a taste for mezcal as a younger man; while passing through Oaxaca, he’d gotten to know the small mezcalero operations that dotted the region. Mezcal is a regional curiosity, specific to Oaxaca, and distilled from the roasted agave hearts. The first samples to appear across the border in Guatemala were irregular bottles with hand scrawled labels of the town of origin, distiller, and maybe a note on its age.

Mezcal was still relatively unknown outside of Mexico, and very few brands were certified for exporting it. Rexer and his staff were left to sate the growing demand in Antigua with the tools available. He still squirms at words like smuggler or bootlegger. “Bringing a few bottles across the border was not such a big deal,” he says, “but try getting 50, 100 or 500 bottles across and things get a bit interesting.”

It was the kind of landscape that made dressing as a priest to avoid suspicion seem like a reasonable idea. “At the borders we were crossing back then, the cops, the military, the gangs and just plain old thieves had to be eluded or navigated or co-opted.”

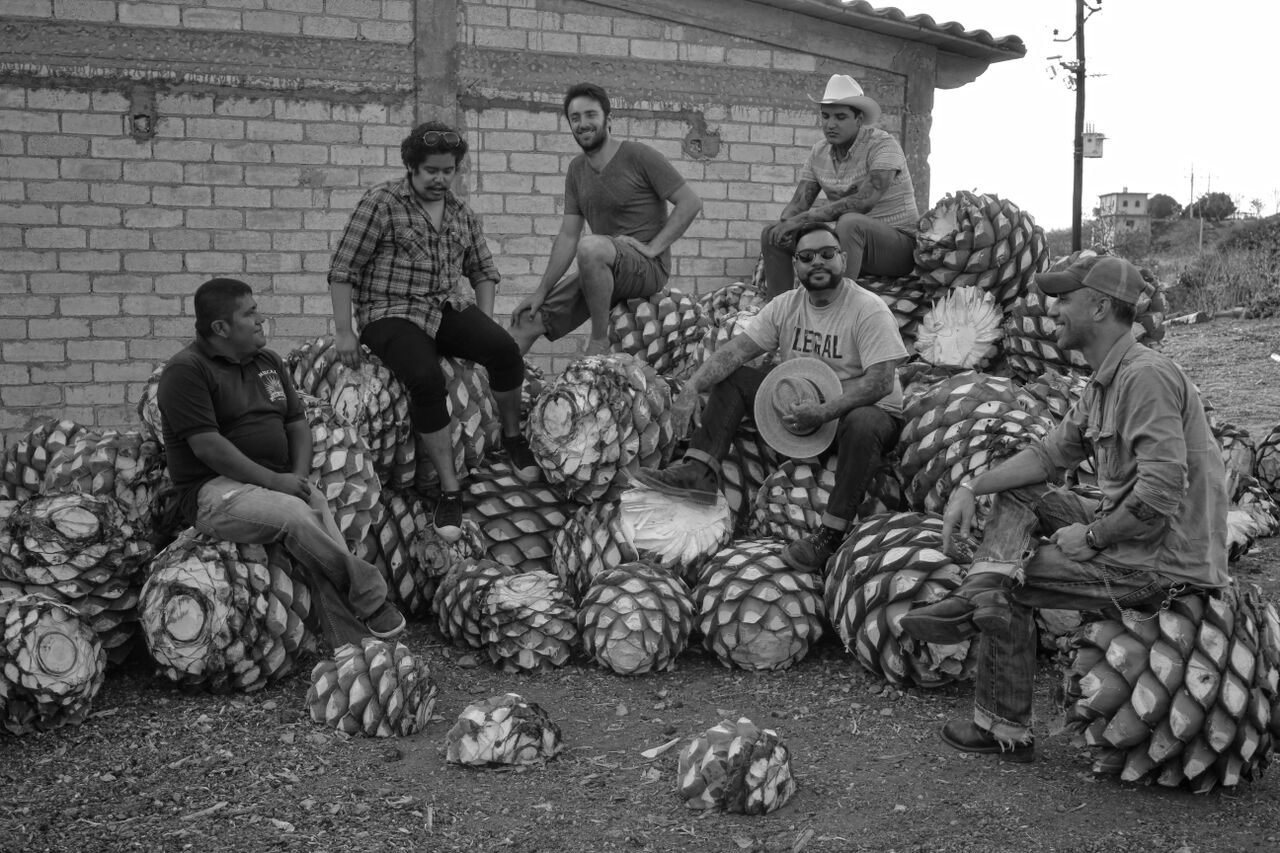

Mezcal is made from the hearts of the agave plant, which are roasted in clay ovens for days before fermentation and distilling. (Photo: Ilegal Archives)

The import operation began a few bottles at a time in 2004. After a few years, demand had outpaced supply by a large margin, and runs to Mexico had become common enough that they interfered with the day-to-day operations of the business. “I was a bar owner with a supply problem,” Rexer explains. Oaxaca is a long way from Antigua, at least a day and half by bus. Running from village to village to buy mezcal takes another couple of days or weeks. “It’s an insane way to stock a bar,” he admits.

Something had to give, and it came as an introduction from one of the mezcal distillers, who knew a man who was involved in the local black market. “This was the first big run,” says Rexer. He “was taken to a warehouse on the border. In front was a popsicle factory and in the back, behind huge metal doors, was a vast space for goods to be taken across the river. When I say goods, I mean TV sets, stereos, prostitutes, car parts, gasoline, toys, animals, pharmaceuticals…you name it.”

The operation relied on the cooperation of local police and military officials on both sides of the border, and buy-in from the notoriously violent gangs that control large swaths of the area. “It’s not a question of if you are going to be ripped off,” he says, “but a question of by whom.”

Finding mezcal for a bar in Guatemala started with buying bottles one at a time in Oaxaca. (Photo: Omar Alonso)

The difficulty of the operation stemmed from the relative obscurity of mezcal. At the time there was no significant global demand for the spirit, so there was also no infrastructure for it to be certified for export. As interest in mezcal throughout the United States and South America grew, a demand for certification and legal export grew with it. In 2005 the Mexican government revised the certification requirements for export and opened to the international market.

Before long the illegal movement of hand-labeled bottles across the border to Guatemala became obsolete and Café No Sé came back to the right side of the law. Exports of mezcal increased more than 300 percent between 2005 and 2011. Bottles produced by the same manufacturer from the outlaw days of Latin American liquor smuggling are now available all over the world, from restaurants in Manhattan to cocktail bars in London.

The only trace of the brand’s shadowy origins is in the name. Rexer’s label, Ilegal Mezcal, pays homage to its early days, of cross-border smuggling to a bohemian barroom in Guatemala.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook