The British Couldn’t Take India’s Heat, So They Imported Ice From New England

Sailing frozen lake water across the world was big business.

When the British swaggered into India in the 18th century, they were paralyzed by the sun-charred summers of the country they had colonized. Many would peel away to the hills for the summer. Others, marooned in the blistering cities, indulged in plenty of mawkish whining. Plain Tales of the Raj, for instance, records one Reginald Savory grumbling, “The wind drops, the sun gets sharper, the shadows go black and you know you’re in for five months of utter physical discomfort.”

The British found various coping mechanisms to tame the season’s cauterizing heat. They slept sashed and scarved in water-drenched garments. They sloshed ice from northern India’s rivers, then drew it to the plains at tremendous expense. They hired abdars to cool water, wine, and ale with saltpetre. They hung wet tatties (mats) made of cooling khus (a type of grass) on their windows and doors. Ice pits were built and small pots of water placed outside on wintry nights. In the morning, the coating of ice that formed was sliced away and stored in the pits, but this ice was usually too gritty and slushy to be consumed.

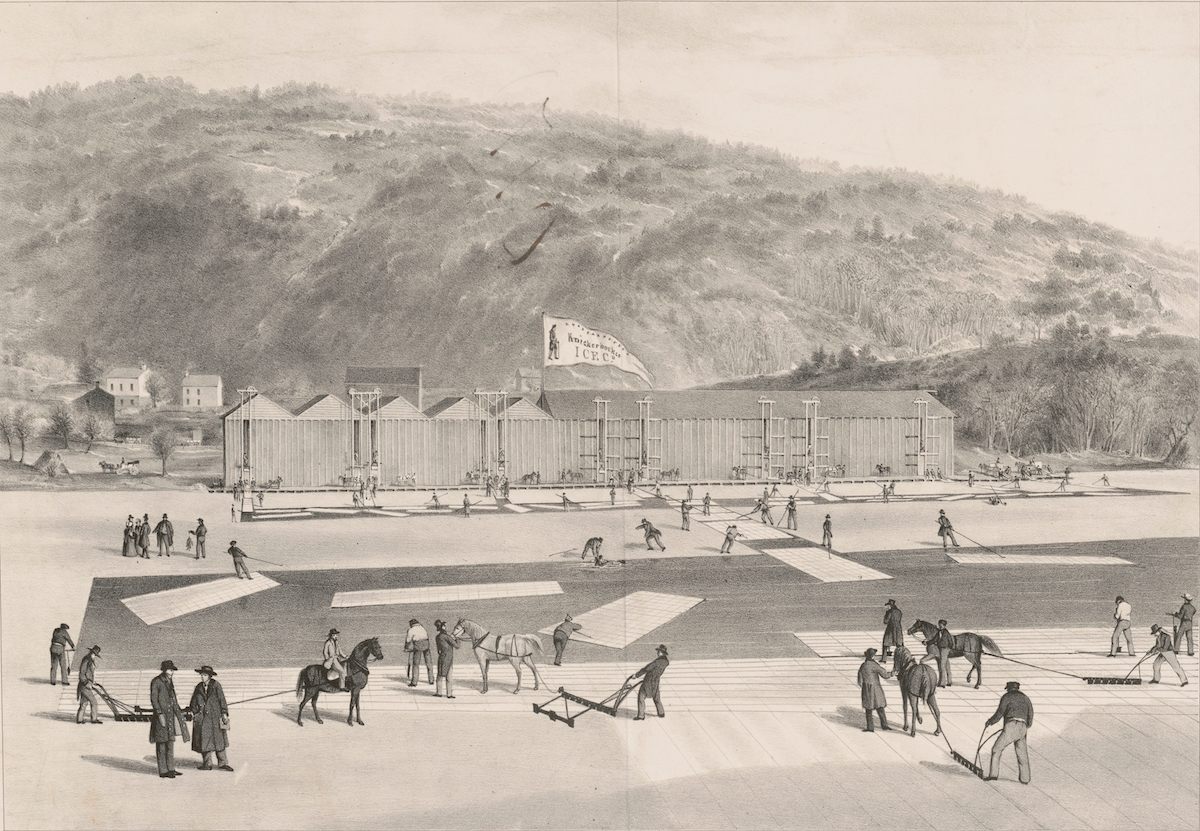

Enter Frederic Tudor, a Bostonian entrepreneur, astute and indefatigable. Tudor dreamt of ice, cut from the ponds of native New England, and sent to hotter climes on constellations of ships. Through the years, he was staggered by bankruptcy, by vagaries of weather, and by the derision of sceptical peers who couldn’t imagine ice surviving such a long sea voyage. “No joke,” reported the Boston Gazette, on Tudor’s first voyage. “A vessel with a cargo of 80 tons of ice has cleared out from this port for Martinique. We hope this will not prove to be a slippery speculation.”

It wasn’t. Tudor solved the full puzzle of harvesting, insulating, and transporting ice long distances. By the time he turned his gaze to India, he had already infiltrated New Orleans and the Caribbean.

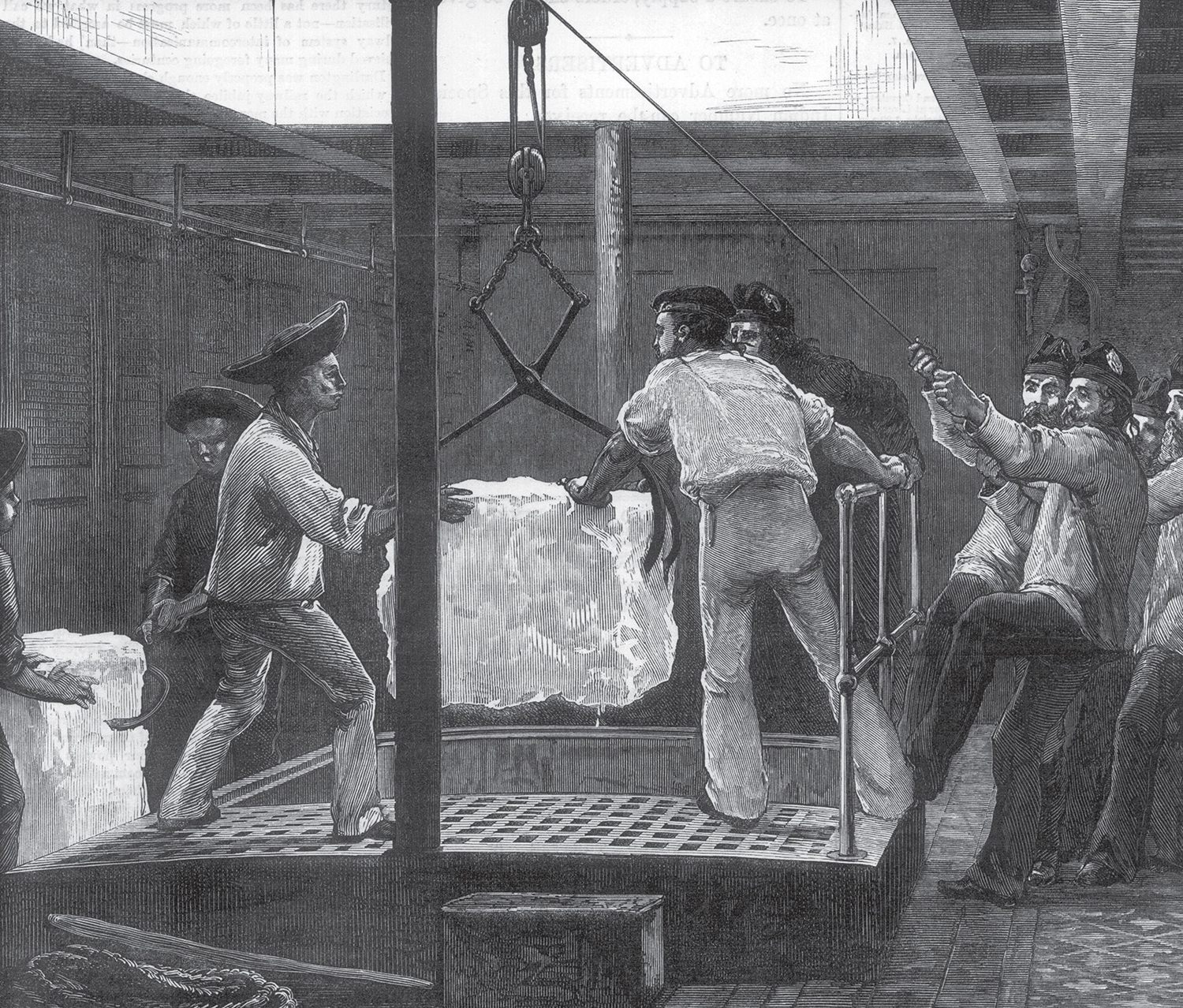

In 1833, he sent forth his first ship to Calcutta. It was packed with 180 tons of pristine ice culled from the lakes of Massachusetts, mantled in sawdust, belted into the ship’s hold in double-planked containers, and sent scudding towards India. Together with the ice went barrels of Baldwin apples—a more reliable export.

Four months later, when Tuscany sailed grandly into Calcutta on September 6, 1833, a thrum of residents beetled their way to the docks to ogle with wonderment at this strange, foreign marvel. It is said that one Calcutta dweller enquired whether ice flowered on trees in America. Another laid his palm on the ice for several minutes, then, jarred by the inevitable blisters on his palm, screamed that he had been scorched as by fire. Yet another urbanite, J H Stocqueler, editor of The Englishman, was in bed when he was woken by the cries of his orderly, vivid with excitement at the news. Tottering back with a piece of this precious cargo, the orderly, alas, neglected to swathe “the ice in cloth nor close the basket lest the ice became too warm.” Consequently, he returned with a nail-thin chink of ice. Some Indians, alarmed at the ice’s brisk disappearance, demanded their money back.

Nevertheless, the ice trade became an astounding triumph, spreading to Madras and Bombay. Along with the ice, Tudor ignited a frenzy for American imports including New England apples and American butter. His business grew fat on a government-supported monopoly and concessions to import tax-free ice. Enormous icehouses began to pock the streets of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras.

Tudor’s ice trade, swollen with success, began to be noticed by Americans—most famously, Henry David Thoreau wrote fleetingly about it in Walden: “Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well.” Tudor became the millionaire Ice King, snagging himself a 19-year-old bride when he was 50 and fathering six children.

At the vanguard of this trade were private clubs in India, set up by the colonizers as offerings of an Elysian British experience, complete with uniformed wait staff serving roast beef and boiled mutton to the administrative elite. The clubs invested heavily in the construction of ice houses; consequently, their dining tables teemed with cold drinks and well-preserved meat. In Bombay, for instance, the Byculla Club ordered 40 tons to be delivered by May 1840, the beginning of summer.

Ice also functioned as a palliative for an antiphony of illnesses, from fever and stomach disorders to kidney defects. During ice “famines” (when ships were delayed), it could only be purchased in limited quantities, and anyone wanting a sliver more needed a doctor’s note. Easy availability of ice became so entrenched that one famine in 1850 produced gales of outrage in Bombay, with the Telegraph and Courier even calling for an agitation.

But while ice from New England was a boon for British colonizers, for Indians, it proved mainly another burden.

It was a delirium of differences. Most Indians, far too poor to purchase such frivolities as American frozen water, and already burdened by heavy taxes, were further throttled by taxation used for building (and later expanding) the icehouses. There were also more humble casualties—the ice trade whittled away at the jobs of the abdars, rendering their positions obsolete. Some Indians availed of ice in major hospitals; many more barely laid their hands on it.

Still, there were exceptions. The first cargo of ice, for instance, was consigned to a Parsi firm, Messrs Jehangir Nusserwanji Wadia. (The Parsis are a tiny community of Indian Zoroastrians, with roots in Iran.) The firm then disseminated the ice to a clamor of Britishers.

Sir Jamsetji Jeejeebhoy, a wealthy Parsi merchant and philanthropist, and the first Indian baronet, was another such. Jeejeebhoy was the first to offer ice cream at a large public reception. Guests gorged on them. A few days later, the Bombay Samachar newspaper wrote priggishly that the hosts and the guests had since been besieged with colds, but having had the temerity to try this “foreign” food, a cold was a fitting penalty.

By 1860, though, ice was no longer considered a treat. “Like most of the conveniences which habit renders familiar, the ice has almost ceased to be a luxury,” wrote the British artist Colesworthy Grant, from Calcutta, in a letter to his mother, “and though little children still continue to seek and to suck it as though it were a sweetmeat, they no longer consider it as the novelty which, when first holding it in their nearly paralyzed fingers, they declared, in amazement, had burnt them!”

Tudor’s vice-grip on the ice trade continued until the 1860s, until, enfeebled by old age, his hold wore thin. Massachusetts lakes, smothered with pollution from new steam railways, lost their allure. Simultaneously, artificial ice-manufacturing units (the first being the Bengal Ice Company) entered the trade, while a skein of new railway lines made it easier to transport the goods around India.

Today, the idea of an ice trade seems almost chimerical. Freezers in Indian homes hold creamy discs of kulfi, while refrigerator shelves are heaped with Thums Up, Sosyo, and other carbonated delights. But a lone ice house still stands near Chennai’s Presidency College. Once containing blocks of ice, it later housed, at various times, a High Court judge, a clutch of poor students, and the Indian sage Swami Vivekananda. Today, most traces of Tudor have been wiped away. Rather poignantly, it is now named Vivekananda House, a paean to the monk and mystic who spread awareness of Hindu Vedanta philosophy around the world and across the seas to the United States.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook