How Firefighters Calculate Containment as They Battle the Sand Fire

California’s deadly Sand fire has been raging for days.

(Photo: National Wildlife Coordinating Group)

A massive wildfire in California’s Sand Canyon—dubbed the Sand fire—has been burning since Friday, claiming at least 38,000 acres of land and the life of one resident.

By wildfire standards, it’s pretty typical for California: it started small, probably somewhere in Santa Clarita, just outside of Angeles National Forest and around 30 miles north of Los Angeles. From there things escalated pretty quickly, and, within hours, thousands of acres of trees and chaparral had burned, helped along by steady winds and dry conditions.

On Saturday, officials found a body: that of Robert Bresnick, who is said to have refused orders to evacuate in an apparent attempt to retrieve some of his dogs. ”He said the fire was burning in his backyard,” a friend of Bresnick’s told NBC4. “I said get the hell out of there! Leave! He just hung up the phone and started to do that, I think.”

And while Bresnick has been the only death, thousands of others were evacuated, in addition to a lot of animals. Around 50 dogs were taken to a local prison to be temporarily cared for by inmates. And elsewhere, the Los Angeles Times reported, there were 165 goats, 111 chickens, and 33 pigs, in addition to over 450 other animals that were rescued.

On Sunday, the fire destroyed the Sable Ranch, which you might remember from the television show Maverick. By Monday, the fire had reached its apex, covering over 35,000 acres.

By early Tuesday, many of the evacuated residents were allowed to return to their homes, after the fire had moved further to the east.

And Wednesday, firefighters said that they were beginning to turn the corner on the Sand fire, with 40 percent of the fire reported to be contained.

Firefighters heading out to battle the blaze. (Photo: National Wildlife Coordinating Group)

At each step that word came up, again and again: “contained.” On Monday, just 10 percent of the fire was said to be contained, a worryingly low figure, since it also means that 90 percent of the fire was uncontained. But by Tuesday that figure had inched up to 25 percent of the fire. And on Wednesday officials reported the good news: they were approaching the point at which they could say that most of the fire was contained.

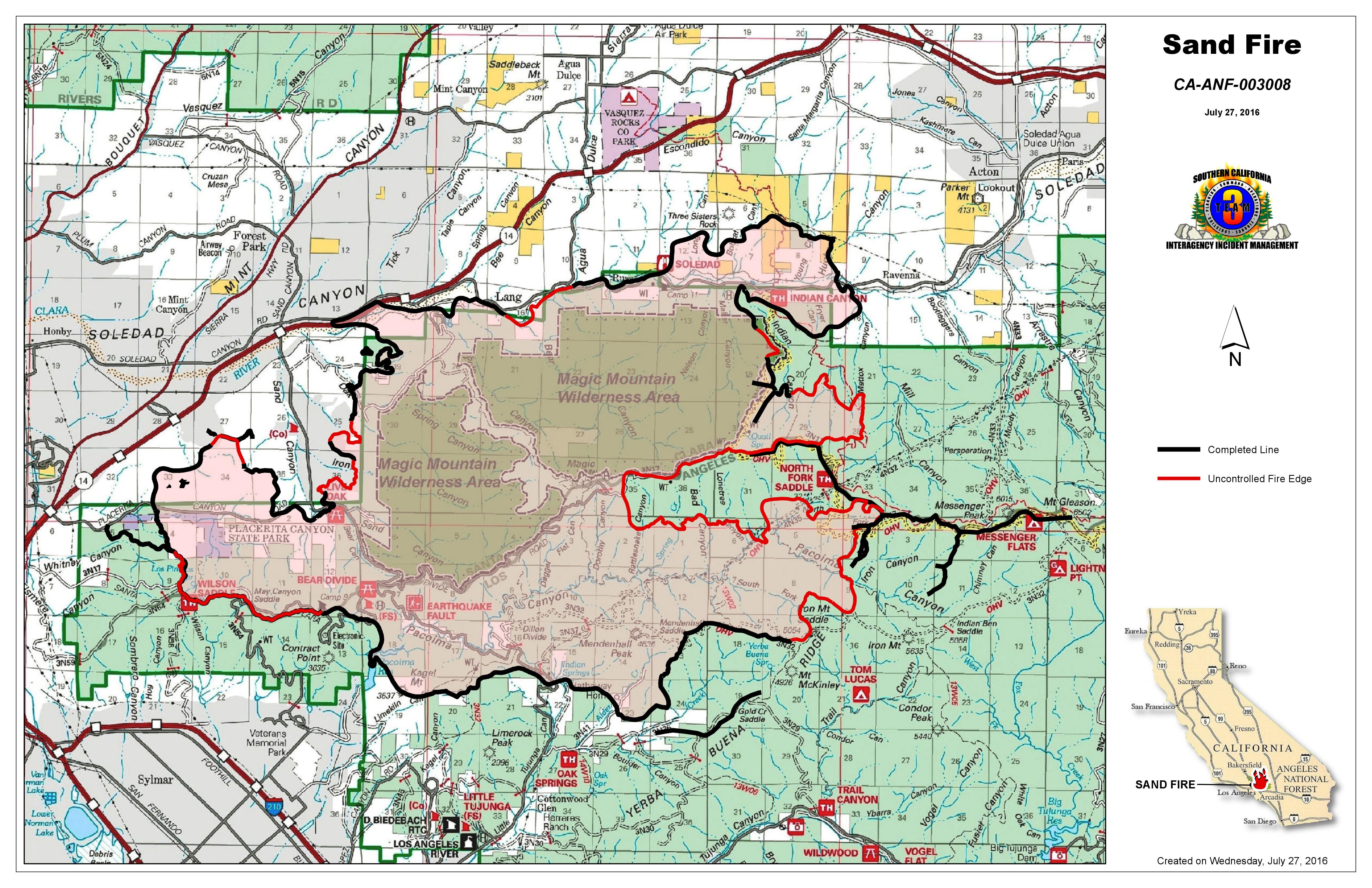

Containment, in this sense, means something pretty simple. Fire officials precisely track a fire’s progress by keeping a close eye on the perimeter of the blaze. Here’s a map from Tuesday that shows their progress:

If you look closely, you’ll see that while the vast ring is mostly red—the “uncontrolled fire edge”—there are some portions of the perimeter that are solid black—a “completed line,” or an edge of the blaze that is no longer dangerous.

Firefighters attack the blaze using a variety of methods, from clearing away wood or foliage that could catch fire, to aerial assaults of fire retardant, to controlled burns, which scorch the Earth before the larger wildfire has a chance to reach it.

The aerial assaults might get the most attention, as they make for splashy photos, but most of the time they only temporarily slow a blaze; crews on the ground then do the real work of halting it. The crews do this by clearing the area of anything flammable and then, often with the help of bulldozers, digging up the soil, and mostly ending the danger from the spreading fire.

This takes a lot of manpower: nearly 3,000 firefighters are at work on the Sand fire, including 275 engines, 12 helicopters, and 29 bulldozers. Compare the above map to a map offered Wednesday to the public:

Black lines abound—the fruits of the firefighters’ labor—and which, added up, account for the official containment percentage.

All of this also helps explain why officials began letting most evacuees back into their homes when the fire was still between 10 and 25 percent contained. Why would they let residents back into their homes while a wildfire was still raging?

Have another close look at Tuesday’s operations map above. The black lines, you’ll notice, are mostly around population centers, while a vast uncontrolled perimeter elsewhere gives way to only more forest, showing that firefighters worked to protect residents, their homes, and local businesses first.

A plane dumping fire retardant on the blaze on Tuesday. (Photo: National Wildlife Coordinating Group)

At 4:15 eastern time on Wednesday, officials posted another update. The blaze was still 40 percent contained, they wrote. But while updates earlier had a tone of urgency, this one felt more routine. Officials thanked a local high school for hosting their command post, while also warning about the danger of exploring areas that were damaged by the fire, or those still being worked on by firefighters.

And then there was a curious reminder at the bottom, noting that firefighters had occasionally spotted drones in the sky over areas of the fire that are still burning. Since the airspace over the fire has been temporarily declared off limits to most aircraft by the Federal Aviation Administration, flying a drone, officials noted, violated federal law. Drones could also interfere with fighting the fire, they said, adding that sheriff’s deputies were searching for those responsible.

“If you fly,” they wrote, “we can’t!”

Firefighting, a practice probably as old as man, had encountered 2016.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook