How Laos Got Its First Buffalo Dairy Farm

First, two friends rented a buffalo.

At dawn, a fleet of orange-robed monks float through the streets of Luang Prabang, Laos, during tak bat, the Buddhist morning alms ritual. Thirty minutes outside town, the staff at Laos Buffalo Dairy gear up for another day, but to a decidedly different rhythm. For them, there might be time dedicated to mozzarella-making, buffalo-milking, and calf-raising. Any given day could also include farmer education, veterinary training, government agency meetings, tours, and one afternoon, a visit from the country’s former President.

It all started with a need for cheese. In 2014, Rachel O’Shea and Susie Martin opened a guest house in Luang Prabang, the former royal capital, as a way to stay in Asia after their expat postings in Singapore ran out. O’Shea, a chef, and Martin, a cheese-loving business executive who named her daughter Brie, became friends over a shared love for travel, taking joint family vacations around Asia. Eventually, they became frustrated with the dairy situation in Laos. As a landlocked country run by a Communist government for years, Laos is behind on infrastructure development and international trade. It only opened up in the 1990s, and the country has no dairy farms: A 200-gram pot of sour cream can cost $12.

They’d noticed buffalo meat for sale at the morning market, though, and eventually asked about buffalo curd. Everyone’s reaction: “You can milk buffalo?” From there, they hatched the idea for Laos Buffalo Dairy. It was a win-win: Farmers would gain extra income by renting out their buffalo during milking season, and O’Shea and Martin would satiate their craving for cheese. “Since they used the buffalo less and less in the rice paddies, it was an under-utilized resource,” Martin explains. “The rental idea came about when we realized farmers weren’t ready to milk their own buffalo, so we had to.”

The only thing to do now was find a farmer who would agree. By word-of-mouth, their idea reached Somlith, the chief of Thinkeo Village, who O’Shea describes as “an outside-the-box, well-rounded man.” She adds: “He sees things other people can’t. We come to him with all our crazy ideas.” They showed him YouTube videos and translated step-by-step instructions. Somlith agreed to a trial run, in which he would rent them three buffalo for six weeks. It took a few attempts, but the herd eventually gave milk, which they brought to the guest house daily.

But turning milk into mozzarella proved to be a trying endeavor. Once, O’Shea found herself crying in the kitchen over a failed batch. “You can’t Google a buffalo mozzarella recipe,” she says. “It’s a small industry and nobody shares it. I emailed 15 cheesemongers and explained how we were a tiny business in a tiny country helping the local community.” Nobody replied, save for a woman from Shaw River Buffalo Cheese in Australia. “She said it probably wasn’t going to work because the fat levels are different, but shared her recipe anyway,” O’Shea adds. That’s because buffalo milk is sweeter than cow’s milk and has twice the fat, which changes the ratio of rennet, citric acid, and salt.

But that lone response proved to be a breakthrough. The pair produced a mess of crumbled mozzarella, which was enough to give local chefs samples. Somsack Sengta, the chef and owner of Blue Lagoon Restaurant, was an early tester. Sengta is a Luang Prabang native who grew up under Communism—back then, “there was nothing in the country, [and] fresh milk only arrived in 1990,” he says. Later, he won a scholarship to culinary school in Switzerland.

These days, he uses the dairy’s mozzarella for his menu, which melds traditional Lao dishes, Swiss classics, and insects. It’s a far cry from those first samples. “The first time, their cheese did not have a good consistency,” he says. “I was using mozzarella from Italy and expected the same quality. And because of the grass the buffalo eats, their cheese had a strong aroma. I grew up with buffalo, so I know the smell. Europeans have a strong nose for cheese, so this would not work.”

Still, restaurants in the area, like his, needed local sources. It was a better option than having brokers from Thailand, Vietnam, and Singapore hand-carry mozzarella into Laos (to avoid sub-optimal shipping conditions). So he kept giving the two feedback. “With locals, you have to say things in a roundabout way, but with Rachel I can be direct,” he says. “And now the quality is there.”

A year after that first tasting, Sengta placed an order. At that point, the dairy needed a steady milk supply. Working with one open-minded farmer was one thing. Convincing entire villages was another matter. “It took us 18 months before the farmers trusted we weren’t going to barbecue or sterilize their buffalo,” O’Shea explains. That’s because for Lao farmers, a buffalo is essentially their bank account: One buffalo is worth 12 million kip, roughly the average annual salary. When a child gets married or someone is in hospital, they sell the buffalo to pay for it. Working with the Laos Buffalo Dairy was tantamount to trusting foreigners—who weren’t farmers—with their life savings.

But many farmers can’t afford the expenses of pens, feed, and vaccines. So, buffalo often fend for themselves and are susceptible to disease. Worse, due to inbreeding, the Lao swamp buffalo population has shrunk over the last 30 years, and they now produce a fraction of milk compared to more robust breeds. The dairy discovered the inbreeding problem when they set up their starter farm, milking up to ten buffalo a day. “Swamp buffalo should give 2.5 litres of milk, but that wasn’t happening,” says Martin. “We were excited if we were getting six to eight liters from the whole herd.”

Martin decided to get help from the Buffalo Research Institute in Guangxi, China. Government agencies in China want Laos to breed buffalo so they can import two million to meet domestic demand. At that point, Laos could barely deliver: The country has 27,000 buffalo, of which 10,000 died during an unprecedented snowfall in January 2016. To help, the institute gave Laos a small herd of murrah bulls, a breed that can provide two to three times more milk. The problem was that they didn’t include cash to support the breeding. Which is where Martin and O’Shea came in. “We’ve got a whole lot of buffalo,” Martin said. “Bring your genetics here.”

With the government now on their side, the fledgling farm picked up the pace. While the breeding program ramped up (buffalo are pregnant for ten months), Dr. Som, a veterinarian who had experience running a dairy, helped with farmer education. Construction soon started on the barns and a cafe.

Finally, O’Shea moved her production from the cramped guest house to the farm kitchen. There, commercial-grade refrigerators line two walls, the staff can prep and pack at a large central workspace, and the room is tiled up to the ceiling. It is unique enough in Luang Prabang that O’Shea sometimes gives tours. Sunlight streams through the large picture windows, where visitors can see a fresh batch of cheese as it drains or watch the staff make ice cream. Once, she says, “the hospital people came out and asked, ‘Can we come and operate in here?’”

Today, 30 locals are on the farm’s staff. Many of them are young graduates with degrees in agriculture and animal sciences, all attracted to the unusual business. None of them had tasted dairy before. Chit Sisanom, who leads the farm tours, remembers the day he tried blue cheese well. “I cannot explain the flavor,” he says. “The smell is very strong; it’s really salty, a bit sour. After I tried a second and third time, it was better. The mozzarella is good.”

Saisamone Chittaphong, a calf specialist, works long hours at the farm during calving season. She had her first taste of dairy when she joined. “Yoghurt is strange, a very pale flavor, just fat,” she says. “Lao people like salty or sweet.” Ice cream, on the other hand, is her favorite, and she especially loves the smell of caramel. She frequently walks down to the ice cream hut, a perk of the job.

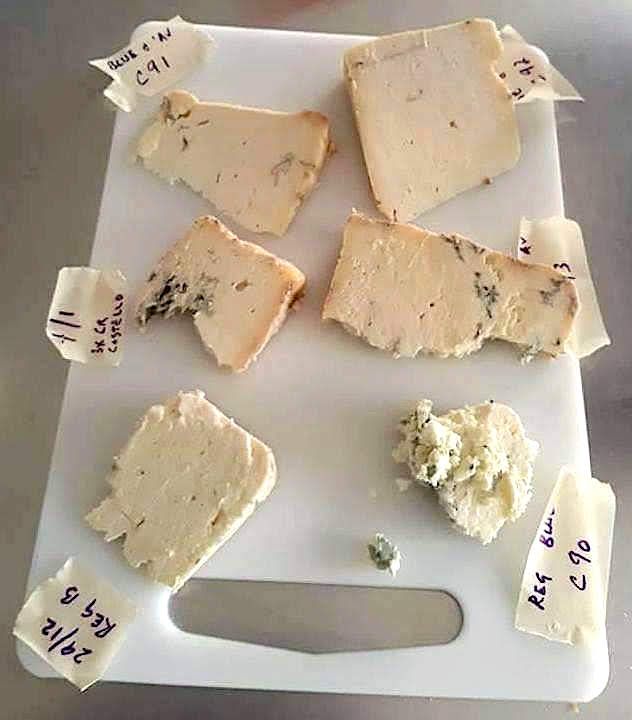

Typically, O’Shea plans production based on the day’s orders. Ricotta, feta, and yoghurt can be made and delivered the same day, while mozzarella requires a two-day lead time so it can brine properly. If there is milk left over, O’Shea takes the opportunity to test new products. Which is why there are batches of three-month and six-month blue cheese ripening in the refrigerators. She’s also testing Camembert, but it was an unfortunate casualty when a circuit blew. Luckily, more Camembert starters are being hand-carried by a friend from the United States.

After a full day on the farm, O’Shea typically packs orders into a blue icebox and loads it onto the company tuk tuk. She’ll use it to deliver mozzarella and other treats directly to the kitchen door of several luxury hotels in the area. These include The Pullman, the newest and largest hotel in town. Executive Chef Marc Comparot heard about the dairy when he arrived three months ago. “At first I didn’t believe my staff that there was cheese 20 minutes up the road,” he says. “I grabbed the car and told our driver, let’s go. I love mozzarella.”

Working with the dairy also fits with local restaurants’ sustainability programs. “If we order from Italy, that product will be cheaper,” Marc adds. “But Rachel and Susie have a fresh product; you have to pay more for that. They are artisans.” The flip side is that the cost can be prohibitive to smaller businesses, although they may be able to decrease prices once they grow.

It looks like the dairy is right on the cusp of that growth. Martin recently returned from LaoFood, a trade fair in Vientiane, the capital of Laos. “Hotels and restaurants have heard about us and are waiting to order,” she says. The Laos-China Railway, which will open in 2020, will also change Laos from landlocked to land-linked. And just last month, a Japanese trader flew in to meet them and wants a ton of product. “A literal ton, 200 kilo of this, 200 kilo of that,” O’Shea says with a nervous laugh. The dairy is now applying for an export license.

The first murrah-swamp cross-breed was born last December, fittingly enough, to Somlith, the first farmer to believe in them. Sophia, seven months old, has long legs and is already as tall as a local female buffalo. Somlith often visits Sophia on the farm. He wants her there, to show other farmers what’s possible. With his extra income, Somlith can send his children to school, pay for electricity, and buy more food for the family. The dairy now works with 150 farmers in 17 villages. Sisanom, the farm’s tour guide, who grew up with buffalo, says: “That’s why the crossbreed is so important. It is impressive for farmers. They see her and realize they can make money.”

As for introducing cheese into Lao daily life, Martin says, “We never intended the locals to be our main customers. But I’m surprised at how quickly they’ve taken to it.” Farm staff who bring milk home often report back the next day with a thumbs-up. On weekends, local families often visit the farm to see the animals and buy milk, too.

It’s dusk on this June day. The two dozen tourists who came today—visiting from all over Asia, the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Australia—have gone. The cheese is packed. It’s a tranquil moment on the farm. This is O’Shea’s favorite time, looking out at the mountains that surround Northern Laos. “Eventually I’d like to be able to put my cheese on a world stage,” she says. “Even if I don’t win, I’d like to know that it was good enough. That was our whole concept: If we were going to make cheese, it wasn’t cheese that’s only good for Laos. It needs to be cheese that is good anywhere.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook