Squirrel Counting Is a Great Excuse to Explore Central Park

A lesson in slowing down and looking close.

Just before nine on a drizzly, slate-colored Saturday morning, the grassy patches and paved paths around Central Park’s Turtle Pond were wild with activity. Runners tore around the track, breathing heavily in the newly chilled air. Dogs—some shaggy, some coiffed, all in various states of muddiness—seemed thrilled to be off the leash, though all, somehow, scampered back to their owners when called. Robins and sparrows and blue jays stayed just out of the melee.

The only thing missing, it seemed, were the squirrels. Maybe they were laying low. If I was going to find them that busy morning, I was going to have to learn to spy on them.

For a few weeks of October—Squirrel Awareness Month, apparently—volunteers with the Central Park Squirrel Census had been systematically combing the park. (This project follows one that the same independent “science and storytelling” team has conducted in Atlanta’s Inman Park.) It’s not unusual to enlist citizen scientists for such efforts, and there’s often a strong ecological or epidemiological reason for monitoring the small creatures who share our environment. Pressing stickers onto the wings of migrating monarch butterflies, for instance, sheds light on whether conservation efforts are paying off. Mining date-stamped tweets for information about spiders or ants can help track the relationship between weather and population booms. The rationale for counting squirrels, though? Maybe a little wobbly. But here’s the thing: “They’re cute, and they’re everywhere, and pretty easy to observe,” said Sally Parham, the logistics chief of the census.

Not so long ago, someone who set out to tally all of the squirrels in New York wouldn’t have needed much time. Before eastern gray squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, were our urban neighbors, they were considered pets, and we imagined them as something like defenseless kittens. In 1856, The New-York Daily Times reported a throng of rubberneckers watching police “rescue” a squirrel that had escaped up a tree. Then, between the 1840s and 1860s, officials introduced squirrels to urban areas as part of beautification efforts in America’s increasingly dense Northeast cities.

In Philadelphia, Boston, and New Haven, they were let loose in grassy squares, where they bedded down in nesting boxes and ate from visitors’ hands. In the Journal of American History, University of Pennsylvania historian Etienne Benson describes urban reformers’ belief that squirrels could help create bucolic oases in the midst of constant change. “The gray squirrel was seen as a particularly desirable park resident,” Benson notes, “since it was understood to be, as the naturalist John Burroughs would later write, an ‘elegant creature, so cleanly in its habits, so graceful in its carriage, so nimble and daring in its movements.’” As a proxy for wilderness, squirrels were ideal tenants for the designs championed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. In 1877, nearly two decades after the first portion of Central Park opened to the public, it opened to squirrels, too.

At that time, the Central Park Menagerie turned a handful of gray squirrels loose in the thickly wooded Ramble. Within a few years, the population had boomed to perhaps as many as 1,500 individuals. It wasn’t long before they began to wear out their welcome. They were accused of stripping bark from cedars and pilfering too many leaves for their nests, leaving unsightly, naked branches in their wake. In 1883, Will Conklin, the director of the Menagerie, proposed culling, which was vigorously opposed by Henry Bergh of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Conklin and company argued that the squirrels were throwing the whole ecosystem out of whack. That year, an unnamed editorial writer took to The New York Times to argue that “nothing but Mr. Bergh prevents the policeman from exterminating the squirrels that exterminated the birds that exterminated the worms that threatened to exterminate the trees.”

Eventually, Conklin got his way. A spell of warm days in February 1886 invited squirrels out in droves, the Times reported—and the park and police force greeted them with a “fusillade.” Early one morning that month, the Times recounted, “sleepy housemaids along Fifth-ave. were awakened at daylight … by the reports of firearms in Central Park,” where “expert riflemen” took down a few feral cats and “fully a hundred fine fat squirrels.” Even so, by the early 1900s, many of the city’s parks had pockets of introduced squirrels, and they were generally considered a welcome addition: The Sun referred to them, in 1900, as “an endless source of delight to visitors, young and old.”

More than a century later, the chance to tally Central Park’s squirrel cohort is a hot ticket. The volunteer sessions fill up, and many of the sighters involved take part more than once.

Some of them are there because they just really, truly love squirrels. Stu Bowler, a five-time sighter, walked me through his favorite squirrel Instagram accounts, and described how, on Friday afternoons, he heads to the park’s wooded Ramble to kick off the weekend with his four-legged buddies. “I’ll sit there, and I may or may not have beers, I may or may not have nuts with me, and I may or may not feed them,” he said. Ten or 15 squirrels come by and sometimes clamber over him, as though his trunk and limbs were those of a tree. For the last five years, he’s also fed squirrels that come and go from the window of his East Village apartment. Just before dawn, and then again around dusk, “they come in for treats,” including avocado and “really expensive nuts.” Bowler and his bushy brethren sometimes hang out on the sofa. The T-shirt he’s wearing out on the census reads, “Squirrels Are My People,” and it has the paw prints and stains to prove it.

Other volunteers were enticed by how kooky the project seems, the promise of free pins and pencils, and the chance to get to know the park a little better. “I honestly didn’t like Central Park that much until I did this,” explained Kelly Reidy, a repeat sighter sporting a bright yellow “Squirrel Census” button. Reidy works as a tour guide at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History, which flank the park’s east and west sides. She’s constantly cutting through to get from one gig to the other, but is usually a little frazzled as she rushes across. “I always think of it as, ‘Ugh, that’s my commute, that’s terrible,’” she said. The census also, incidentally, provides a primer on the park’s geography and landmarks. The pursuit of bushy-tailed residents led Reidy to Summit Rock, one of the highest points in the park. Wandering around portions that were less familiar to her “helped me fall in love with it a little bit,” she said.

For me, the park has never been a tough sell. I’ve been enamored since the week I moved to New York, and discovered a place along the Lake where the traffic sounds are muffled almost beyond recognition. Still, armed with my clipboard and a pen, I saw my old love through the dreamy, fugue-like light of a new crush.

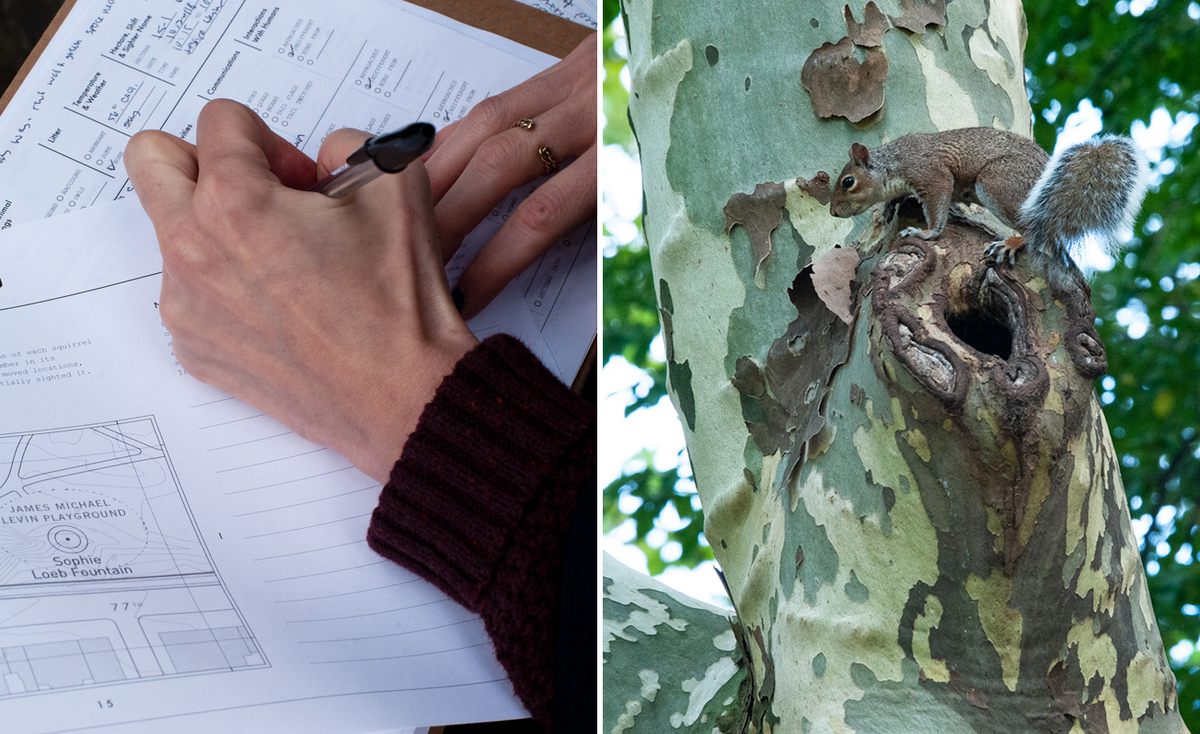

The census organizers gridded the park and its borders into 378 hectares, 349 of which were included in the count (the others are in water). “We created our own planning map to overlay the hectare grid onto the park,” explained Nat Slaughter, the project’s chief cartographer. Each of the countable hectares was scouted by a sighter twice to measure squirrel activity at different times of day. During each shift, every participant was assigned a hectare or two, and instructed to scour it for squirrels, who may be foraging in the dirt, racing up a tree trunk, or nesting in their shaggy dreys made from leaves and sticks. I made my way from the King Jagiełło monument next to the 79th Street Traverse, down to the bronze statue of Alice in Wonderland, just north of the pond where visitors can helm remote-controlled model sailboats.

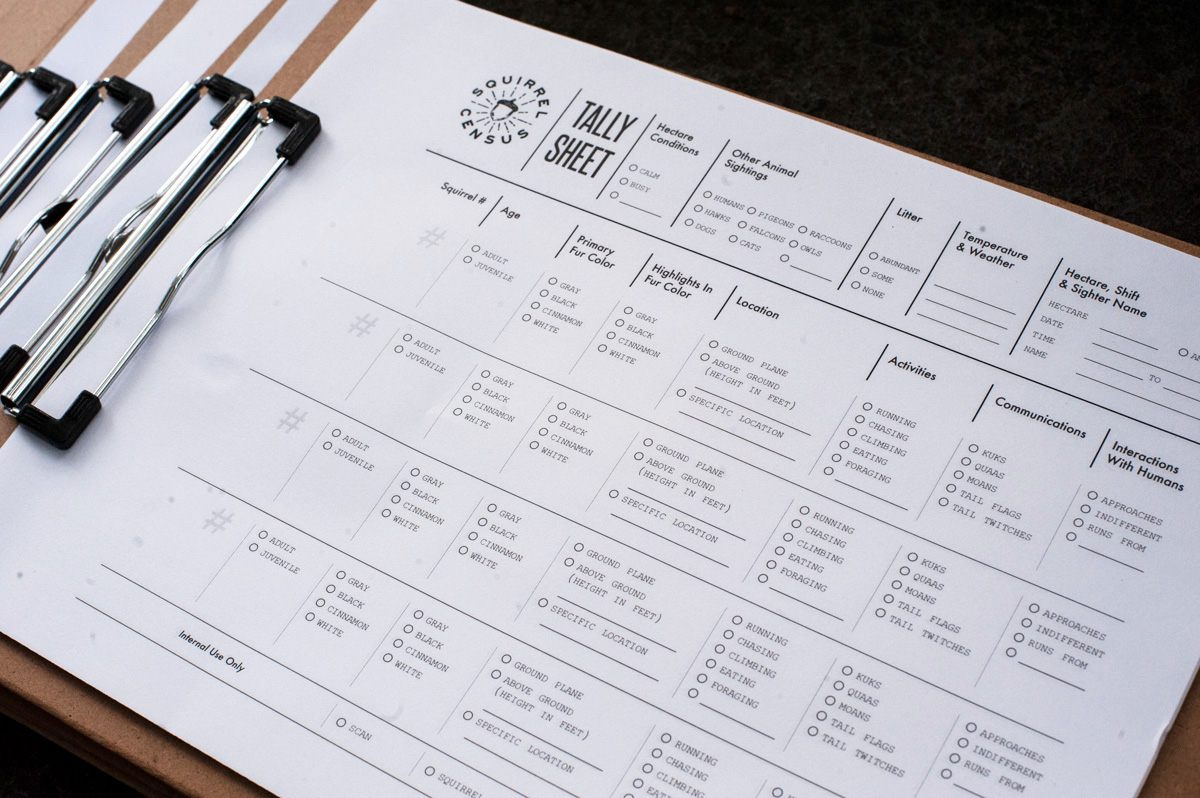

There, in hectare 14-I, with my ears alert and pen poised, I searched. Parham, the logistics chief, had reminded me to walk slowly, look closely, and be fastidious with my notes on physical appearance, behavior, and location. I needed to record whether a squirrel was gray, black, or cinnamon-colored, and what it seemed to make of me (did it approach, ignore, or flee?). I needed to indicate whether an individual was an adult or a juvenile—a tough distinction because they look pretty similar, though juveniles tend to look more “perfect,” while the adults “look like they’ve lived a little,” Parham said. I also had to take stock of how the squirrel was communicating. Did it flick its tail or let loose any barking kuks, bleating quaas, or moans?

In a given shift, which lasted around two hours, a Central Park sighter may see no squirrels or a whole slew of them—23 is the max so far. I saw seven, pawing through crunchy leaves, roughhousing in branches, and leaping around, seemingly oblivious to bicycle traffic and the march of carriage horses. My sightings will be collated, and the organizers intend to release their total count in the spring.

As I flitted my eyes around my hectare, I found myself becoming attuned to the minor excitements of the natural world. I homed in on quick, quiet movements, from hopping birds to breeze-tangled leaves. I observed a lot of other activity I might not have otherwise noted: a cluster of people doing tai-chi in the grass, a hawk arcing low above the canopy, friends sharing a bagel on a bench, toddlers’ shoes squeaking as they scaled a bronze sculpture.

Reidy told me that one unexpected wonder of the census has been passing by the same people each time she went out, just going about their business, such as the woman she saw every day, tossing a ball for her pint-sized dog while chattering away on her phone. “That’s their thing,” Reidy said. In pursuit of squirrels, I think I learned a little bit about our own species, too, and the little joys of a public space that becomes a shared backyard.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook