How Pleather Saved the DuPont Company—And Some Cows, Too

It’s been around for decades.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

As any cursory watch of an episode of Happy Days will tell you, we’re obsessed with the look of leather—but perhaps not fans of the way leather is produced.

Much like a meal at McDonald’s or a fur coat, we’re more impressed with the final result without any worries about where it came from—because thinking about where it came from potentially raises some heavy ethical questions.

For the plastics industry, it’s long been the perfect opening for a synthetic alternative, and there are plenty of varieties out there, most made from variations of vinyl. Pleather has put up quite a fight in an effort to upholster our cars and replace the linings of our shoes, thanks to the fact that it’s cheap and can be chemically treated in ways that leather can’t. So why hasn’t it won out quite yet?

Well, in some ways, it has. Just not in the places you might expect.

If it weren’t for Fabrikoid, there’s a good chance the chemical conglomerate DuPont might never have become a household name—and General Motors might’ve gone bankrupt long before the financial crisis of 2008.

Like plastic and fabric melded together using a chemical process, the history of the first pleather and GM’s DuPont era are hard to tear apart.

Here’s how it happened: The company’s first modern-day president, Eugene du Pont, died in 1902, offering the company something of a clean break from the past. The firm wanted to find more mainstream uses for their chemical know-how, but that proved challenging at first. Hilariously, for example, the company produced a 1910 manual titled “Farming With Dynamite,” which sounds like the punchline to a great joke.

That same year, however, DuPont was able to find a durable path forward with its purchase of the Fabrikoid Company. The leather substitute maker was a great fit for the company, but not a perfect one, as the material was a little lacking. But DuPont’s chemical experts worked to turn the pleathery acquisition into something groundbreaking.

It helped that the material represented something of a bridge between explosives and consumer goods: Fabrikoid was made with a combination of pyroxylin (a nitrocellulose coating that had previously been used as a plastic explosive called guncotton) and a fabric pigmented with the help of castor oil. After a bit of tweaking, DuPont had a leather alternative that was good enough to put in a car.

DuPont soon found other uses for its chemicals, including another variation on pyroxylin called Pyralin, an early ivory-like form of plastic.

Fabrikoid’s connective tissue proved key for the du Pont family as it staked out a path to the consumer market in the form of the automobile. Starting in 1914, the family began acquiring a significant amount of General Motors stock, soon gaining full control of the company by taking advantage of its precarious financial situation. The family saw some pretty synergistic opportunities in GM—the kind that eventually draw antitrust regulators.

“Our interest in the General Motors Company will undoubtedly secure for us the entire Fabrikoid, Pyralin, paint and varnish business of those companies, which is a substantial factor,” DuPont executive John J. Raskob wrote in 1917.

Raskob was right about that synergy: GM bought many of its raw materials from DuPont for decades, and the C-suites of the two companies soon had much in common. For example, Pierre S. du Pont was GM’s president at one point, and Raskob, who started as Pierre’s personal secretary, was for a time in charge of the finances of both companies.

Synergy or no, Fabrikoid was along for the ride. DuPont saw significant success with its pitch for using faux leather as the upholstery option of choice in automobiles, with leather alternatives making up 70 percent of the car market by 1915, much of it made by the chemical firm.

“It has the artistic appearance and luxury of real grain leather, and in addition is waterproof, washable, and will outwear the grade of ‘genuine leather’ used on 90 percent of the cars that ‘have hides’,” the company stated in an ad that year.

But neither the investment nor Fabrikoid were built to last. Eventually, newer pleather technologies reached the public, many of them using stronger vinyl mixtures, and by the 1940s, Fabrikoid was old news.

Around that time, the whispers around DuPont and GM’s overly cozy relationship reached fever pitch, and the Truman and Eisenhower administrations started to take an interest.

A breakup that big, however, isn’t one that happens overnight. It wasn’t until 1957—more than 40 years after the du Ponts bought their first interests in GM, and after an antitrust trial that went all the way to the Supreme Court—that the ultra-cozy relationship was broken up. The du Pont family finally divested themselves of GM stock in 1961.

Raskob’s laying-it-all-out-there quote was cited in the Supreme Court’s decision.

Fabrikoid was a footnote in DuPont’s history by that point—but an important one. It was the first of many success stories for DuPont in the textile space—paving the way for later substances like nylon, polyester, and Teflon.

Not bad for fake treated cowhide.

DuPont wasn’t alone in popularizing pleather, though; alternatives were commonly pushed by all sorts of firms.

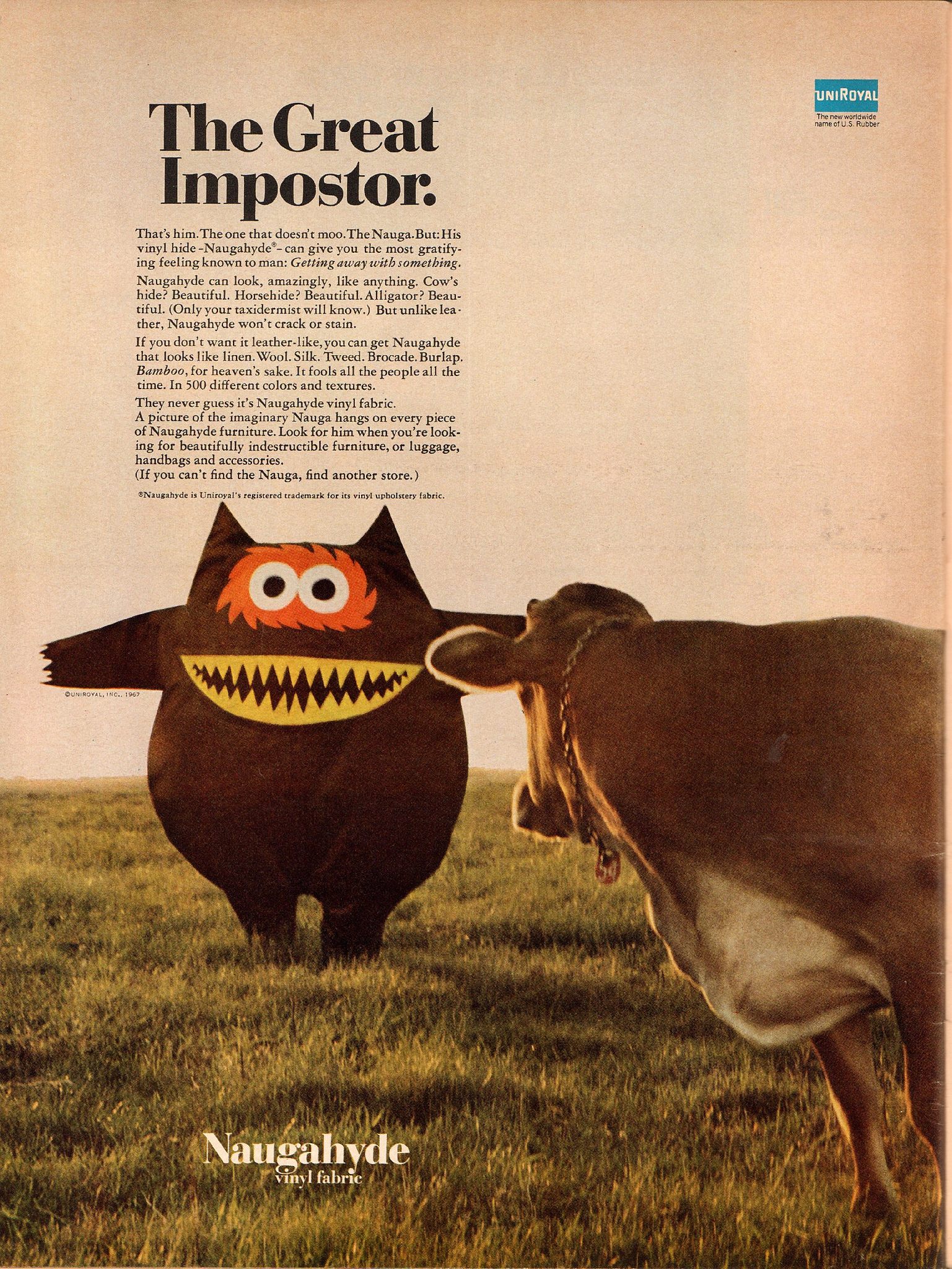

And sometimes, the thing that really stood out wasn’t their fake leather, but their brilliant marketing. For example, Naugahyde, a product created by Uniroyal in the 1930s, became notable for its ad mascot, a fake animal called the “Nauga” that, unlike most animals, loved shedding its hide.

“Naugas do give up their hydes. But they do it willingly and they shed their skins quite often,” a description of the “Nauga” on an old version of the Naugahyde website stated. “They live to give again and again. In fact, Naugas are so willing to please that they often shed their hyde several times a year. No self-respecting hunter would ever try to hurt a Nauga.”

The “Nauga”—an unusual animal with an impressive leather-style hide—was the work of 1960s ad man George Lois, who came up with the strategy to promote Naugahyde, a particularly snazzy looking variant of pleather. The story of the animals was almost too successful, and as a result, Snopes has a page letting the public know that naugas are, in fact, fictional. Naugahyde, a creation of Uniroyal from the 1930s, is still sold today, and the Nauga dolls tied to the old ad campaign remain popular collector’s items.

Back in the Nauga’s heyday, clever marketing was necessary to get the public to even think about buying pleather. But these days, the has gotten a bit of an upgrade in the world of fashion—as well as a slightly different name. In a 2013 interview with The Cut, fashion designer Joseph Altuzarra sang the praises of the advantages pleather (er, excuse me, “poly-leather”) has over similar materials, including traditional leather.

“The poly-leather is incredibly luxurious, the way that it wears over time,” he said. “It doesn’t wrinkle. It travels really well. It’s waterproof, so if you wear it in the rain it completely repels water. There’s something sort of magical about its properties.”

Altuzarra has even combined pleather with real fur in some of his pieces. The Cut’s Jillian Goodman describes pleather as “one of the rare trickle-up fabrics, moving in the last decade from the sex shop on the corner to racks at Barneys.”

Often, faux-leather is purchased with the goal of not hurting any animals, which seems like a perfectly valid reason for not wearing leather if you’re not into that sort of thing.

But from a resource standpoint, it’s a lot more complicated than that. In 2011, Mother Jones‘ Kate Sheppard raised the question of whether pleather was really all that much better for the environment than its derided carnivore cousin. She notes that, from a raw materials standpoint, buying a single pair of leather shoes that last a decade or longer versus a pair of faux-leather shoes that last maybe six months, it’s not really a contest.

“You’re better off focusing on something you know you’re going to keep for a long time, that’s going to stand up to the care or not need as much care,” Texas State fashion merchandising professor Gwendolyn Hustvedt told Sheppard.

And then there’s the problem of chemicals, which is Greenpeace’s main beef with the use of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) in many leather products. In a 2002 interview with the Environmental Magazine, the organization’s Lisa Finaldi noted that the toxins expelled in the creation of PVC are far worse than the environmental impact of killing a cow.

“Leather has environmental problems as well, but it doesn’t have the global impact of PVC,” Finaldi explained.

If you’re feeling ethically challenged by both the pleather and the leather in your life, perhaps the solution here is to meet the two materials halfway. There’s a name for that, actually: It’s called bonded leather, and it’s the result of recycling old leather, adding a new fabric backing, and combining it with chemically treated plastic. It looks nice enough, and it’s often used to upholster furniture. And recyclers can even gather up used leather from old shoes to help create the material.

That said, Consumer Affairs argues that if you’re buying a couch and quality is your goal, you’re better off with the real thing.

But on the other hand, at least you wouldn’t be killing any more cows.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook