How the Smithsonian Institution Is Crowdsourcing History

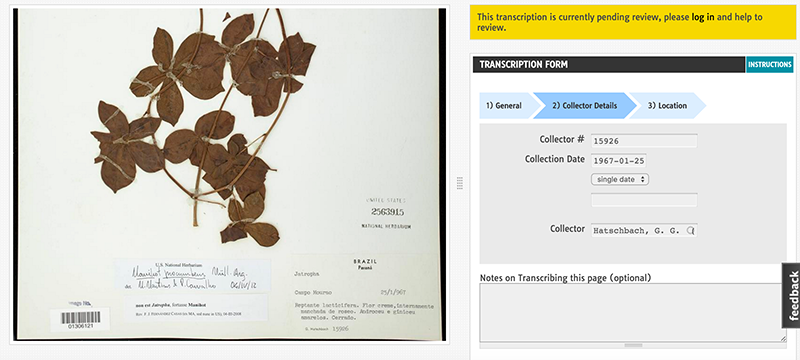

A transcription in process of Euphorbs from U.S. National Herbarium. (All Photos: Courtesy Smithsonian Transcription Center)

It’s the end of the day, you’ve worked hard, and now you’re home and it’s time to relax. So you open up your laptop and settle in to transcribe some bee specimen labels. Or the packing list of a space shuttle. Or the field notes of a naturalist tromping through early 19th century Ireland.

It may sound odd, but plenty of people would rather parse the curly, old-fashioned handwriting of a bugle player in a Civil War military band than stream an old episode of Breaking Bad, as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s online Transcription Center. So far, 5,883 volunteers from around the world have transcribed more than 150,000 pages from over 1,000 projects.

This effort exists because of a simple fact: just digitizing something isn’t the last step in making something useful to scholars or the general population.

“Digitizing materials is really important but that’s not the only step to making them accessible,” says anthropologist Meghan Ferriter, project coordinator of the Transcription Center.

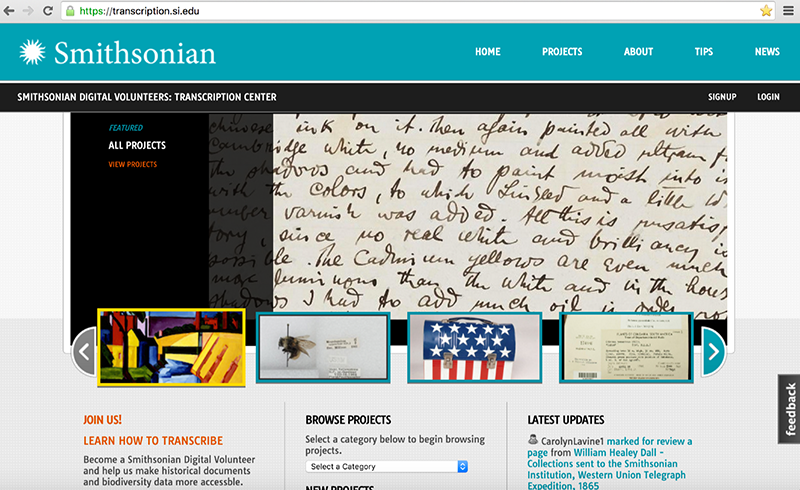

Launched in 2013, the project invites anyone with access to a computer to choose from a buffet of documents supplied by 14 of the Smithsonian’s libraries, archives and museums. Volunteers participate anonymously or create profiles, and each project comes with specific instructions. Participants read scanned pages and type their transcriptions into a field below. Many users work on multiple projects in small chunks, so that any given text is transcribed by a team. Transcriptions are reviewed by fellow volunteers and then signed off on by a Smithsonian staffer before being declared complete.

The Transcription Center homepage, showing Oscar Bluemner papers from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Research institutes have rushed in recent years to digitize their holdings, but without transcriptions, text-based assets can’t be searched. Turning hardcopies into searchable text opens up a new world of research possibilities and plenty of institutes are getting on board. Curious gourmands can take part in the New York Public Library’s effort to transcribe historic menus. (In 1901, a plate of calf’s liver and bacon in the Union Pacific dining car would set you back 40 cents.) The National Archives is crowdsourcing the transcription of photo captions from the National Forestry Service and works documenting Wounded Knee. You can dig into women’s diaries or the history of the transcontinental railroad via the University of Iowa Libraries or bivalve specimens through the Australia-based Atlas of Living.

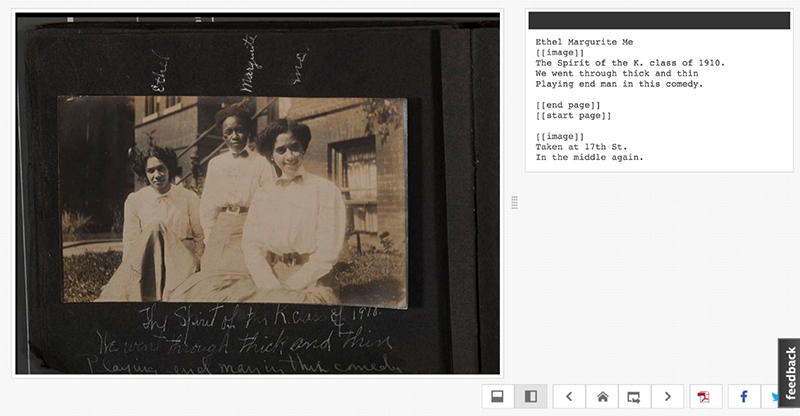

The scrapbook of soprano Lillian (Evans) Evanti, from the Anacostia Community Museum Archives, has been transcribed.

But beyond searchability, transcribing also unlocks obscured histories.

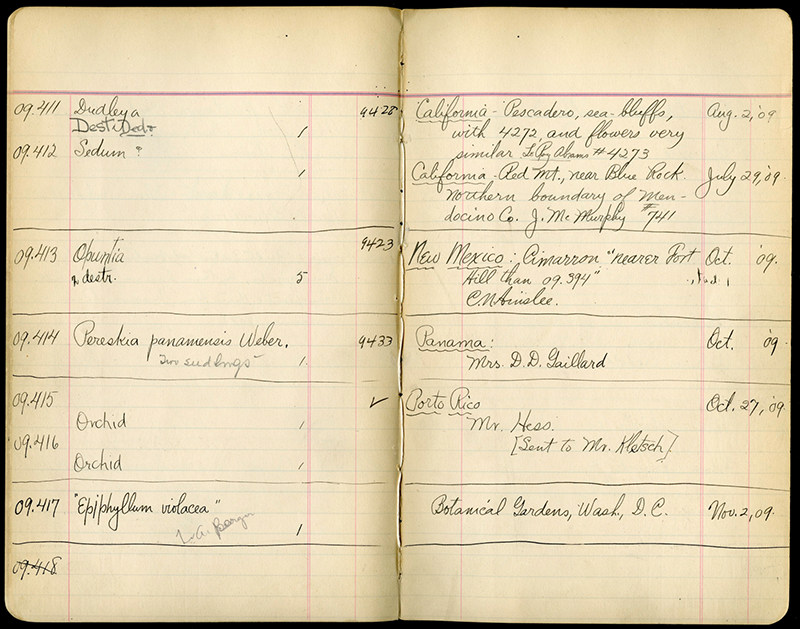

“The set of discoveries I like to point to—because it’s particularly powerful—were in field notes written by Joseph Nelson Rose,” says Ferriter. “Who has a perfect last name for a botanist.”

During the early 20th century, Rose was tasked with making inventories of samples submitted to the U.S. National Herbarium, a kind of library for plants that today is one of the largest in the world. As volunteers combed through records, they started to notice something: Women’s names. Both trained and amateur female botanists had been sending samples to the herbarium on a level previously unknown; some were hidden behind the names of their husbands or other male counterparts, as is common in historic records. Not only has this prompted the Smithsonian to revise their records to reflect such contributions, but moved volunteers to boost the visibility of several of the 27 women cataloged in Roses’ records. Now Ellen Quillin—a botanist and author who resourcefully opened a sensational reptile garden in order to keep her San Antonio museum afloat during the Great Depression—has her own Wikipedia page.

Joseph Nelson Rose’s field notes.

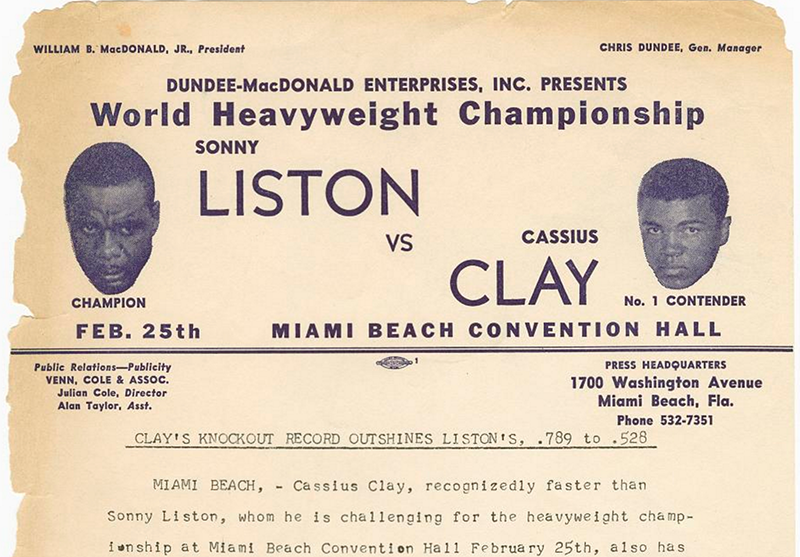

The Transcription Center has also made searchable for the first time a collection of letters from author James Baldwin and the promotional kit for Muhammad Ali’s legendary fight against Sonny Liston—his last fought under the name Cassius Clay.

There are, of course, some projects that attract more users than others. Apollo space mission inventories were “snapped up” and completed in two days; a medieval manuscript written in Latin and shorthand has been slower going.

Out of this effort, a kind of community has sprung up. Volunteers bond over their projects on a Facebook and Tumblr and in the comments on individual projects where they leave each other tips on, say, how to tell a writer’s “n” from their “s”. Ferriter rewards users—who she calls “volunpeers”—with behind-the-scenes chats with curators and collections managers.

Promotional material from Muhammad Ali’s fight against Sonny Liston, from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, has also been made searchable.

But even without such carrots, a quick dip into the archives reveals why someone might spend their free time transcribing yellowing documents, namely that the artifacts present a tantalizing connection to the past: Journals are dotted with curious drawings and small mysteries. Is that blotch the remainder of a long gone cup of coffee? A raindrop? A tear?

For Ferriter, the joy is in the details. She recalls a section from the diary of Mary Henry, socialite daughter of Joseph Henry, the Smithsonian’s first secretary. In one of her entries she describes a chance encounter with George Armstrong Custer, the Civil War cavalry commander who would die at the infamous Battle of Little Bighorn. Ten years from his demise, Henry describes him as “a fair haired blue eyed man with a fine broad forehead” who flew past her on his horse like the wind.

“It’s these smaller observations,” says Ferriter, “That are pretty interesting.”

Update, 2/10: An earlier version of this story referred to the Smithsonian Institution incorrectly as the Smithsonian Institute. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook