A Database of 5,000 Historical Cookbooks Is Now Online, and You Can Help Improve It

It took Barbara Ketcham Wheaton more than 50 years to compile The Sifter.

In the early 1960s, Julia Child and her husband handed Barbara Ketcham Wheaton the keys to their home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The famous couple was going to California for the summer, but they wanted their young neighbor to be able to continue one of her favorite activities: perusing Child’s collection of historical cookbooks.

Now an honorary curator of Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library Culinary Collection, Wheaton was then in her early 30s, with young children at home. She had left an art history PhD program a few years before to marry historian Bob Wheaton, but she still had a passion for the past. When she discovered her love of cooking, and her neighbor’s trove of unique books, Wheaton wondered: What if she turned the same methodology she had learned in art-history classes to a more humble text—the cookbook?

During long afternoons, Wheaton buried herself in the Schlesinger Library’s historical-cookbook collection. And she ventured to her neighbor Julia’s house, to pore over the famous chef’s cookbook collection. Wheaton didn’t know it at the time, but her curiosity about the books’ stiff pages, full of strange stains and descriptions of vintage sauces, would soon turn her into one of the best-known scholars of culinary history. “I started looking at old cookbooks and one thing led to another,” says Wheaton.

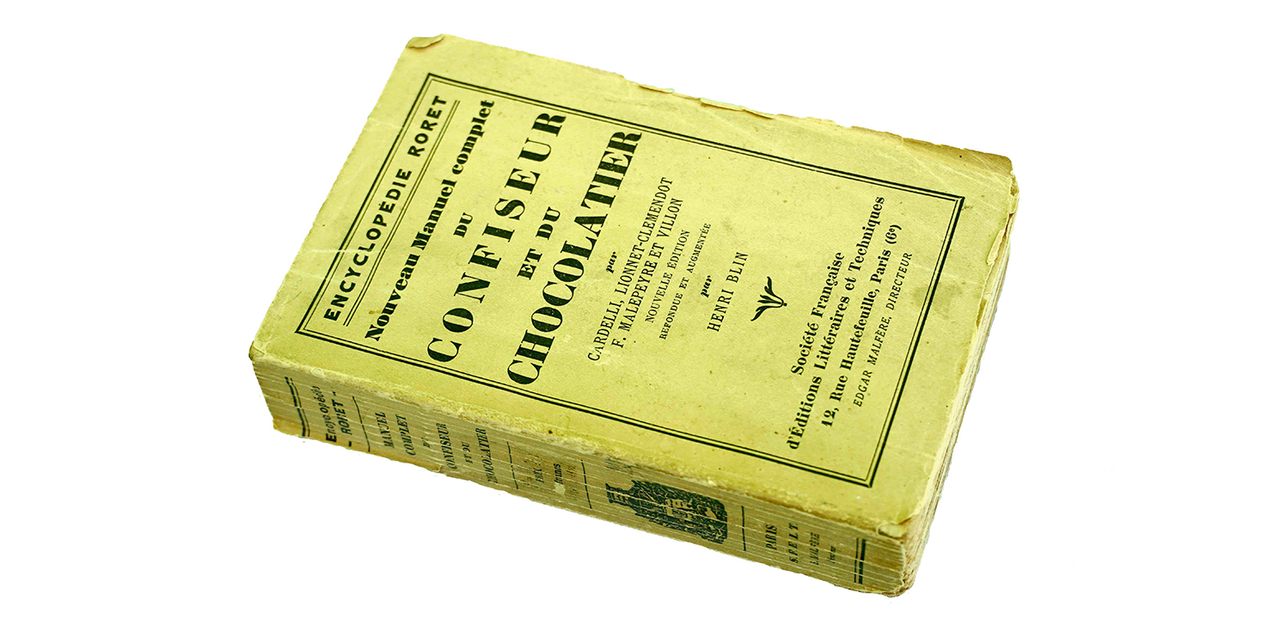

Now, the public can enjoy the fruits of Wheaton’s 50 years of labor. In July 2020, Wheaton and a team of scholars, including two of her children, Joe Wheaton and Catherine Wheaton Saines, launched The Sifter. Part Wikipedia-style crowd-sourced database and part meticulous bibliography, The Sifter is a catalogue of more than a thousand years of European and U.S. cookbooks, from the medieval Latin De Re Culinaria, published in 800, to The Romance of Candy, a 1938 treatise on British sweets.

The Sifter isn’t a collection of recipes, or a repository of entire texts. Instead, it’s a multilingual database, currently 130,000-items strong, of the ingredients, techniques, authors, and section titles included in more than 5,000 European and U.S. cookbooks. It provides a bird’s-eye view of long-term trends in European and American cuisines, from shifting trade routes and dining habits to culinary fads. Search “cupcakes,” for example, and you’ll find the term may have first popped up in Mrs. Putnam’s Receipt Book And Young Housekeeper’s Assistant, a guide for ladies running middle-class households in the 1850s. Search “peacock” and you’ll find the bird’s meat was sometimes eaten from the 1400s to the 1700s in courtly England.

Wheaton hopes the website will be useful more complex projects. She suggests, for example, using the site to track the relationship between cookbook authors’ gender and the value of the ingredients included in their recipes, as a way of measuring gendered economic and cultural capital over time.

The story of The Sifter’s genesis similarly reveals the connection between gender, labor, and prestige. When Wheaton got started as a culinary historian, as a young mother 60 years ago, “I couldn’t have a PhD, because there wasn’t a PhD in the field until we invented it,” she says. At the time, there was a split in the academy around the study of domestic labor, such as cooking. On one side, traditional historians—predominantly male—considered the history of food to be unimportant, even vulgar. “Food history has been a bit of an embarrassment to a lot of academics, because it involves women in the kitchen,” says Joe Wheaton, a professional sculptor and member of The Sifter’s advisory board.

Western scholars had a bias against studying sensual experience, the relic of an Enlightenment-era hierarchy that considered taste, touch, and flavor taboo topics for sober academic inquiry. “It’s the baser sense,” says Cathy Kaufman, a professor of food studies at the New School, and a member of The Sifter’s advisory board, of culinary pleasure. “It’s bestial. It’s animal.”

At the same time, newly minted feminist historians were engaging in a contentious debate about the role of food and domestic labor in women’s oppression. While some feminists advocated for reclaiming cooking as a way of recognizing women’s historically undervalued creativity and labor, others felt this simply rehashed the sexist notion that women’s proper place was in the kitchen. Some scholars, says Wheaton, accused her of “celebrating the oppression of women.”

But Wheaton took a more pragmatic approach. Though options for income and independence were limited for most women throughout European history—and though male cookbook authors were, and continue to be, celebrated and compensated above female authors—Wheaton says that, for many women, skill in the kitchen was a ticket to relative economic stability. “If you were a good cook working in a reasonable family, you had a life that wasn’t that bad.”

Thanks to passionate scholars, the status of food studies began to change in the 1980s. In 1981, a group of researchers held the first Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery. Wheaton joined the Symposium two years later, after her first book, Savoring The Past, a history of French cuisine from 1300 to 1789, splashed onto the scene. “It was magisterial,” says Kaufman, of the book’s scope and ambition. “No other book had tried it.”

Wheaton’s big innovation was in developing what she dubbed a structured approach to studying historical cookbooks. She methodically analyzed each element of a cookbook, including its ingredients, the kitchen layout and technologies that its recipes assume cooks have access to, the author’s suggestions for menus and meal planning, the book as an object, and the role of the cookbook in the broader society. That sweep of ambition made Savoring the Past a success. “I was astonished,” Wheaton says.

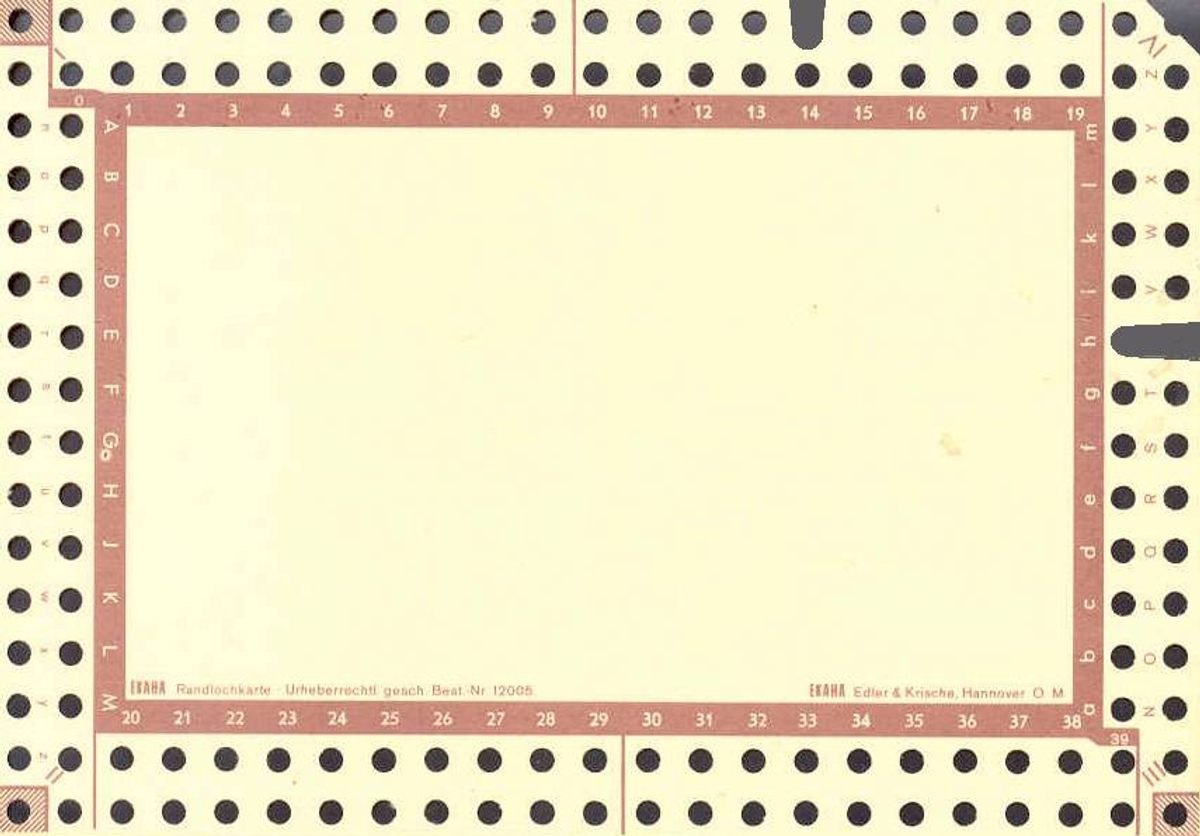

But Wheaton had a problem: The scope of her ambition outstripped the technology at hand. She envisioned a sweeping catalogue of cookbooks, like a landscape seen from a satellite, that would allow her to map the contours of culinary history—the shifting trade routes, the fickle food fads, the new technologies. Researching her book in the late 1970s, Wheaton used a system of stacked cards with punched holes around the edges, each precise formation of holes representing particular categories. When she wanted to see all the works in a particular category—say, books that mentioned peaches—she slipped a knitting needle through that series of holes. “Which is useless for more than eight pieces of information,” Kaufman says.

In the late 1970s, when Wheaton was working on her book, the cutting edge in computing was the Boston Computer Society, which had been founded by a 13 year old. By the time Savoring the Past was published, IBM had finally come out with a computer that could record information with French accent marks. Wheaton began logging her notes digitally. It took almost 30 more years—until just this July—for Wheaton’s database to launch.

Today, The Sifter’s lengthy spreadsheets and clunky search functions may admittedly seem less than flashy to younger people, who never had to use a knitting needle to perform a data search. But once you get the hang of it, the website’s 130,000 references—each one painstakingly entered from Wheaton’s notes—are little bursts of light shone on the past.

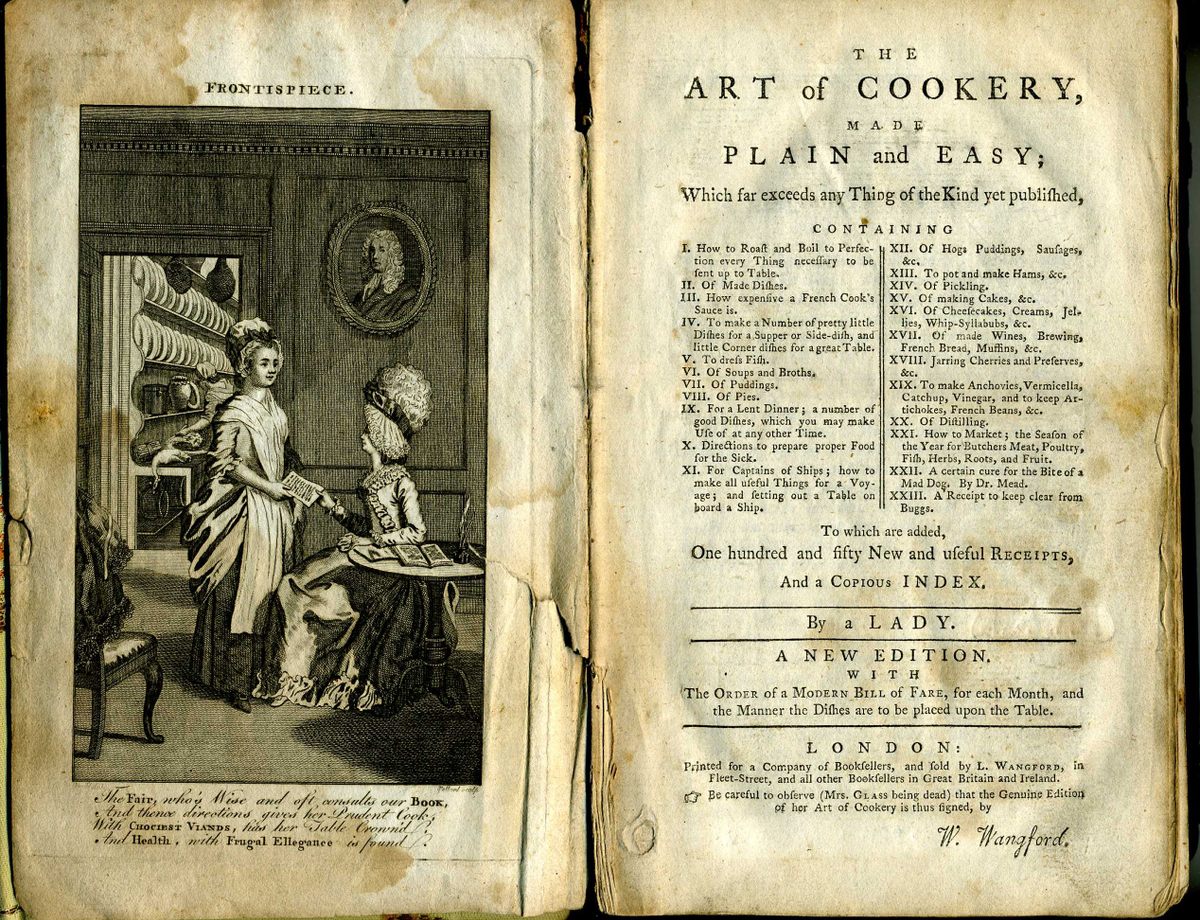

A search for “cheesecake,” for example, will result in 189 references, including Robert Abbot’s 1790 recipe for almond cheesecake, Hannah Glasse’s 1805 recipe for lemon cheesecakes, and E. Smith’s 1742 recipe for potato or lemon cheesecake. If this research on the evolution of cheesecake makes you want to learn more about Robert Abbot himself, you’ll find that his 1790 Housekeeper’s Valuable Present or Lady’s Closet Companion also included instructions for how “to make very good wigs.” Another quick search will yield that in the late 1700s, “wigs” were a kind of bun or scone, rather than a style statement—but that, as in Hannah Glasse’s work, cookery books of the era often did contain recipes for both wigs (buns) and to “preserve hair and make it grow thick.”*

You can explore The Sifter’s search functions at home. Try tracing the history of your favorite dish, the evolution of cinnamon use in France or Germany, or the popularity of very good wig (or very good hair-care) recipes. The Sifter is also a work in progress, and it’s relying on the community to expand what Wheaton started. You can register for an account to contribute translation expertise or input cookbook information, from any pre-1940 cookbooks you might have on hand, or from an internet archive.

If you do contribute to The Sifter, you’ll be in good company. Wheaton, now 89 years old, is celebrating the launch of her life’s work through virtual chats with her children and collaborators, and by doing what she loves best: reading cookbooks. “I live in a retirement community where I don’t have to work on anything practical,” she tells me over Zoom, framed by the bookshelf behind her. “The thing I longed for when the kids were small and growing up was to be able to work on the stuff all the time. And now I can.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this article confused “wigs,” the 18th-century bun, with wigs, the hair piece.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook