How Ireland Embraced Seaweed Pudding

Irish moss has a long culinary history.

This article is republished from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

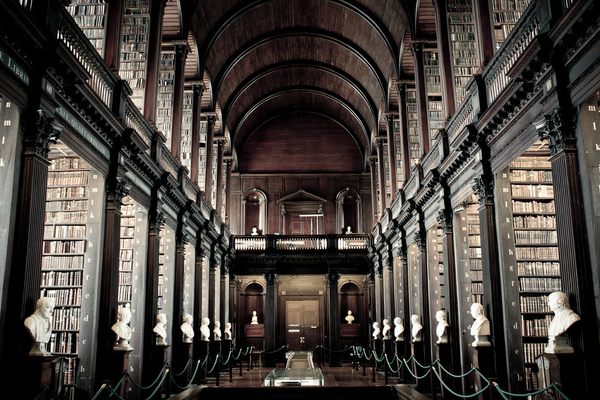

I’d like to tell you that I found out about Irish seaweed pudding while leafing through chronicles in a university library. Or by hearing about it in an old pub late one night. But it’s just something that popped up on Twitter. “Carrageen moss pudding,” someone tweeted while discussing traditional fare. I blinked. Then looked it up. A form of blancmange made with carrageen, a common seaweed on Ireland’s coast.

Despite growing up in Northern Ireland, I had never heard of this dessert. I asked a few friends but they, too, were oblivious.

Regardless, I was fascinated by the thought of combining dairy and seaweed. It seemed so bizarre. What on Earth did it taste like? I had to make it. And so I ended up in my kitchen one evening with my wife, pouring warm water into a bowl over a small clump of dried carrageen, or Chondrus crispus to give it its Latin name.

Commonly called Irish moss, carrageen grows all over the Irish coast, in rocky places and estuaries. But it is distributed around the world, growing in similar habitats in much of Europe, Canada, the United States, and parts of Asia. A branching alga, carrageen is easy to identify in the sea by its vibrant red, undulating fronds.

The carrageen in my bowl is brown and crusty. But the seaweed unfurls instantly when touched by water, taking on its customary glossy red color and silky texture. It has a whiff of the sea at this stage, slightly astringent and with some ocean griminess to boot.

To the touch, carrageen feels like a piece of tough, ultra-smooth and wet leather. But the odd thing about it is the immediate slipperiness of its rehydrated surface. This is the first awakening of the jelly that has begun to seep out of it. When I taste the seaweed at this stage, it is not salty. Rather, it has a hint of iodine, more medicinal than marine.

Having revived the carrageen with warm water, I lift it out and place it in milk for boiling. Various recipes that I discover online suggest boiling it in the milk for 20 minutes, which I do. This process forces a surprising amount of jelly out of the seaweed, causing the milk to become very gloopy. The milk also takes on a gentle purple hue—and a heady tang of the beach. At this point, I lift out the carrageen and discard it. Tough and chewy, the seaweed itself is inedible.

Then, I whisk an egg yolk, some sugar, and a drop of vanilla essence into the milk. To produce a slightly foamy texture—picture an embryonic meringue—I fold in a separated, whisked egg white. Once light enough, I pour the mixture into a small serving bowl and leave it to set in the fridge for a few hours. As it chills, I wonder how it will turn out. I’m expecting something light, a melt-in-the-mouth blancmange but with a unique character in terms of either flavor or texture.

My research suggests that the pudding spread to lots of places in Ireland—in part, perhaps, thanks to its blandness, many viewed it as suitable fare for the ill and infirm. The late 19th-century Handbook of Invalid Cooking by Mary Boland contains a simple recipe for the dish. It has “an agreeable taste,” writes Boland, “resembling the odor of the sea, which many like.”

Boland claims it’s the mineral content that has medicinal value, but she doesn’t say which minerals or why they would be good for you. Still, carrageen has long been viewed as a curative, says Prannie Rhatigan, a doctor and food writer based in County Sligo in the Republic of Ireland.

“It’s absolutely steeped in Irish folklore,” she explains. “Every granny would have a recipe not just for the pudding but a remedy for a very bad chest.”

That meant anyone with bronchitis might be offered a kind of gelatinous hot toddy. Seaweed-touting grannies of the past would simmer the carrageen in water and then add lemon or maybe a bit of whiskey, Rhatigan says. Lucky them. For a moment, I am thankful my own grandmother had no such recipe.

Intriguingly, carrageen has been the subject of various medical studies and clinical trials. These tend to involve not clumps of seaweed but the concentrated extract carrageenan, which is added to pharmaceutical nasal sprays.

Researchers have long investigated the cold-busting properties of this medicine, with some tentative but intriguing results—for example, as a treatment for the common cold. Lately, its efficacy against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has become the focus of scientific investigation. One study published last year by a team in Argentina found that carrageenan stunted the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in a lab-based experiment. However, some controversy surrounds the extract: A review published in 2021 noted that long-term consumption of food-grade carrageenan might be associated with intestinal inflammation.

Still, many people in Ireland prize the medicinal potential of traditional foodstuffs. Prior to making the pudding myself, I met Michelle Wilson, who runs a local business that makes food and cosmetic products from seaweed. As a former healthcare worker, she told me she was fascinated by the potential health benefits of these algae. Wilson must be fortified by something: It was 7:30 a.m., quite chilly, and she stepped straight into a rock pool, allowing the cold water of the Irish Sea to seep into her light shoes.

“It’s just something you need to get used to,” she remarked, nonchalantly picking her way over the pebbles as I balanced above the waterline nearby. But there, just next to us, we found fresh fronds of carrageen swaying in the tidal shallows.

Locals in Ireland can harvest small amounts freely, and some small businesses also forage for it, but carrageen has been cultivated on a larger commercial scale—for example, in Canada. Carrageen farmers are generally after the extract carrageenan that is a thickening and stabilizing agent in a myriad of products besides nasal sprays, from toothpaste to baby formula.

No one is sure whether the current extent of carrageen harvesting is harming the distribution of the seaweed in Ireland or not. And while it seems to be plentiful, the Republic of Ireland’s Marine Institute has funded drone surveys to study the country’s seaweed situation and is considering how to map carrageen stocks.

“On a personal level, I feel that, down the road, if we want to use seaweeds, we are going to have to start looking at the cultivation of them as opposed to targeting wild stocks all the time,” says Liam Morrison, a marine scientist at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

While the interest in industrial and pharmaceutical uses for carrageen seems robust, I am less sure what the future holds for the old pudding—it seems a labor-intensive, hardly foolproof, and potentially rather dull dish.

As I lift my first attempt out of the fridge, my heart sinks. It is obviously a disaster. It has not set, forming instead an unpleasant sort of milk soup with a froth of whisked egg white floating egregiously on top. With the weight of Irish heritage pressing strongly on me now, I redouble my efforts—and triple the amount of carrageen at the simmering stage—on my second attempt. The quantity of jelly exuded this time seems at first excessive, the mixture positively wibbles before even having had time to set. After not very long in the fridge, it reaches an acceptable level of rigidity. I take it out, sprinkle some icing sugar and a pinch of chopped mint on it, and dive in.

The flavor is difficult to describe. Certainly, an earthiness touched with that signature of iodine is detectable, but overall the result was disappointingly bland, just as Mary Boland promised. If I were an invalid, I’m not sure I would appreciate it any more deeply.

I later read that many people add punchy flavors to enhance the pudding. Pear and ginger. Or rum and raisin, even. The chef named Ireland’s young chef of the year in 2019 made a carrageen pudding drizzled with local honey.

These were thunderbolts of inspiration. Plus, when I foraged on the beach with Wilson, she told me there was once a fashion for adding brandy to the dish. She also said she planned to make a version with coconut milk and poitín, a traditional Irish spirit that is occasionally flavored with various essences, such as, in Wilson’s case, hazelnuts. “It was amazing,” she told me later, via email.

Perhaps this is how best to elevate the pudding from the invalid’s bedside. Treat the mixture’s blandness as a blank canvas or a mere vehicle for flavor. Marry its delicate texture with sweet, zingy flavors—as well as a little bit of drink—and this traditional fare could clearly delight for centuries yet.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine, and is republished here with permission.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook