How to Forage From the World’s Oldest Tree

These “living fossils” are everywhere; their nuts are delicious.

This article is adapted from the October 30, 2021, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

The other day, I was cooking galbijjim: stewed short ribs. According to Maangchi’s Big Book of Korean Cooking, by the supreme online cooking teacher Maangchi, this dish is often made for birthdays and holidays, and it is accordingly lush with jujubes, pine nuts, chestnuts, and ginkgo nuts.

Lacking that last ingredient, my mind wandered down the street, to where my neighbor’s four ginkgo trees were all dropping fruit.

I’ve always liked ginkgo trees. I have a set of gold hair clips shaped like their fan-like leaves, and every fall, I go on a walk to see their foliage turn from Kermit green to glorious gold.

I often regret those walks. Afterwards, sitting in a car or any enclosed space, it becomes obvious that I’ve stepped on a popped ginkgo fruit or ten. These tiny orbs look innocuous, but their smell—like vomit-laced poop—is so awful that I’m frowning just thinking about it.

It always makes me happy, though, to see people gathering the fallen fruits. Inside each orb, after all, is a dense, nutty, delicious kernel. Used across East Asian cuisines, they’re lauded for their texture as well as their purported health benefits.

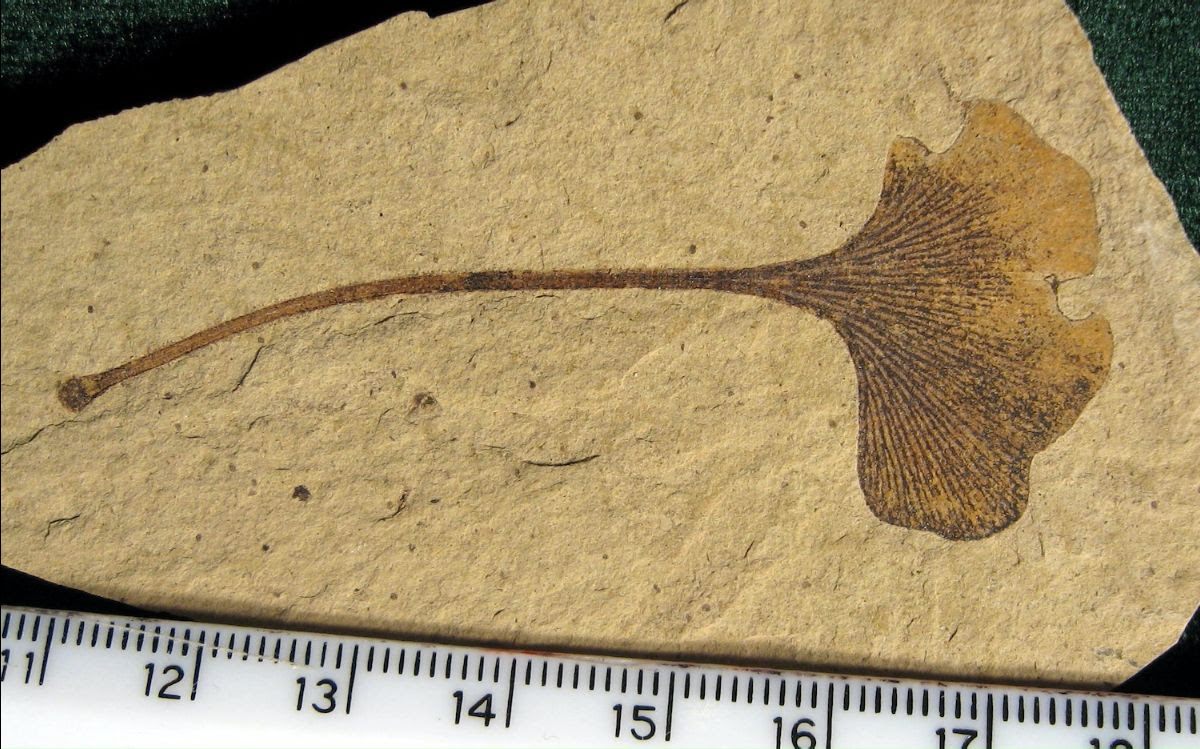

So this week, we consider the gingko, a tree of paradoxes. They drop infamously smelly fruit, yet line city streets; the seeds are delicious, yet underutilized; and it’s commonplace, but also the oldest living tree species on earth, an actual “living fossil” that people regularly walk by without a second thought.

Trees Before Time

Seeing a ginkgo biloba tree on a city street is the arboreal equivalent of seeing a T. Rex at Starbucks. In fact, the fossil record shows that ginkgo biloba trees existed in their current form as far as the Middle Jurassic Period, or 170 million years ago.

“If we could go back in a time machine, maybe we would find some differences,” Peter Crane, a botanist and author of a biography on gingko trees, once mused. “But I suspect not.”

While ginkgos grow from Peoria, Illinois, to Pretoria, South Africa, they didn’t get there naturally. Wild ginkgos only grow in China, where they survived millennia of climatic shifts after the region’s unique geography kept it a tad warmer than much of the rest of the world.

But humans happened across this tiny population of holdouts and propagated them for their foliage and fruits. According to Gifts From the Gardens of China, by historian Jane Kilpatrick, Chinese monks especially enjoyed ginkgos and planted them around their monasteries. In the 1700s, European botanists saw the trees for the first time—curiously, the very first of them wrote extensively about the edible nut but not at all about the smell—and went to great lengths to grow ginkgo from seed.

Ginkgo and the City

Now, they’re everywhere, especially in cities. Why? They’re a city planner’s dream. They root deeply and don’t need much pruning. Plus, nothing can kill them. Hard, dry, salty soil? They don’t care. Choking air pollution? They don’t care. Their leaves even have a toxin that repels insects and pests that would otherwise damage them.

Gingko trees are so strong, in fact, that when the U.S. devastated the Japanese city of Hiroshima with a nuclear bomb on August 6, 1945, six ginkgo trees near the heart of the blast survived. They lost their leaves, but several are still alive and growing today.

People planting urban trees in the 19th and 20th centuries made a bit of a devil’s bargain. Planting a ginkgo meant gaining a long-lived, generally low-maintenance street tree, but with the trade-off being that the female trees dump pounds of goopy fruit in the fall. Since there’s no way of telling if a ginkgo is male or female until they reach maturity, planting fruit-free trees often wasn’t an option.

Taste Test

Since these smooth-textured treats can be enjoyed in soups, braised dishes, or cooked and eaten on their own, the nuts are often available in grocery stores that sell Chinese and Korean products. But here’s how to gather them yourself, whether off the tree or off the curb. (Note: Ginkgo pulp contains urushiol, the same compound that makes poison ivy itchy. People who are highly sensitive to poison ivy shouldn’t touch ginkgo nuts.*)

1) Forage the Fruits

Find your local female ginkgo tree, which will likely start dropping fruits in late September and early October. Aim to find unbroken nuts. First things first: glove up before you touch.

2) Bathtime

Once you get home with your bounty, dump the seeds into a container of water and rub them with your still-gloved hands until the outer pulp sloughs off. (Leaving them to soak for a bit makes the process easier.) Carefully pour away the pulpy water, and rinse until the smell mostly disperses.

3) Into Hot Water

Then, start a pot of water on the stove, and when it boils, add in the seeds in their hard shells. Boil for 10 minutes, then fish them out with a slotted spoon and let them cool. Using pliers or a whack from the flat of a knife, remove the shells. Then, rub away the dark outer skin, revealing the shining kernel within.

4) Two Warnings

Bear with me here! Dishes usually come with only a few ginkgo seeds, since they contain trace amounts of a neurotoxin that can cause nausea and headaches. Don’t eat them raw, and people with certain health conditions should avoid them. Generally, it’s considered wise to limit yourself to 10 nuts a day, maximum.

5) Get Ready for Ginkgo

The kernels are good in soup and desserts, or toasted in a skillet and eaten on their own. Try Maangchi’s galbijjim recipe, or, for something sweeter, this dessert soup made with snow fungus, longan, rock sugar, and, of course, ginkgo.

Update 11/8/21: This article was edited to include more information on the potential adverse reactions that some people have to ginkgo nuts.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook