Ancient Egypt’s Ibis Mummies Were Probably Not Raised in Giant Sacred Ranches

Genetic research suggests a more local solution to meet demand.

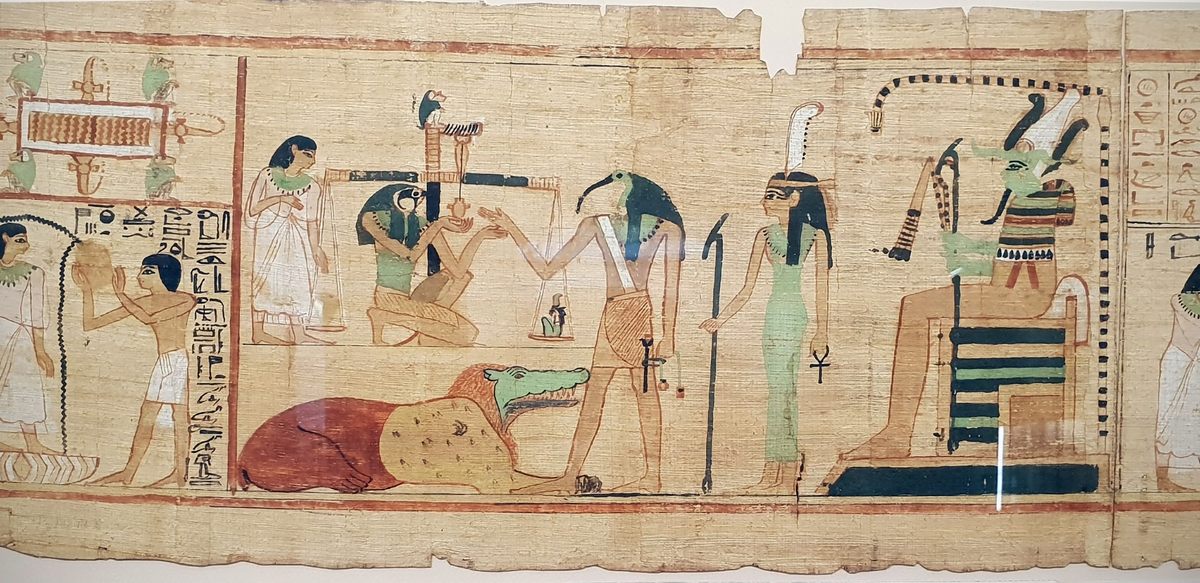

The ancient Egyptian pantheon abounds with animal-headed gods—Sekhmet (lion), Horus (hawk), Thoth (ibis), and others—and accordingly there are lion, hawk, and ibis mummies. These preserved animals have turned up everywhere from pharaoh’s tombs to city necropolises. Ibises in particular have been found by the millions, but archaeologists have not had concrete evidence of how the birds were acquired to be sacrificed by priests, who then mummified and sold them as devotional offerings. Were they domesticated and raised on an industrial scale or captured from the wild? Now, research published in the journal PLOS One suggests the latter was more likely.

“To investigate the possibility of domestication, we used ancient DNA stored in the ancient Egyptian ibis mummies to tell about how the priests ran their business,” says Sally Wasef, a paleogeneticist at Griffith University in Australia and lead author of the study. “We analyzed and compared the mitogenomic diversity among these mummies to that found among modern sacred ibis populations from throughout Africa.”

Mummies were in extremely high demand in ancient Egypt. At temples and necropolises, devotees could purchase a small animal mummy to ask for a god’s favor or pay respect to the dead. This meant there was big business in the animal mummy trade (and, in turn, for forgeries, made up of other animals). The ibis mummies, crammed (ceremoniously) into conical jars, folded beak over body, would mostly have been made in honor of Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom, writing, and magic. That array of symbolism made ibis mummies among the most popular offerings, hence the millions of dead birds strewn across Egypt.

There are five major ibis mummy–packed catacombs in Egypt: Abydos, Thebes, Kom Ombo, Saqqara, and Tuna el-Gebel, the last alone hosting some four million ibis mummies. While ibis farms did exist—a practice known as “ibiotropheia”—it is not known if they alone could account for all the mummies. Wasef’s international team of scientists took DNA samples from 14 ancient ibises and 26 modern birds. The ancient ibises turned out to have genetic diversity akin to that of today’s wild birds, indicating that they hadn’t been subject to domestication, which would have made them more genetically similar to one another over time.

“[The evidence] suggests a more likely scenario,” Wasef says, “namely that priests sustained short-term taming of the wild migratory sacred ibis at local lakes or wetlands for the ritual yearly demand, contrary to the suggestion of centralized industrial-scale farming of sacrificial birds.”

It appears that the great Egyptian religious ibis mummy industrial complex was a little more local and bespoke than once thought.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook