The Harrowing Tale of American History’s Worst Cross-Country Road Trip

The 1919 journey convinced Eisenhower the government needed to improve the United States’ roads.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, contrary to popular belief, did not build the federal highway system for the sole purpose of evacuating cities in the event of an atomic war. But there was one key military endeavor that did influence Eisenhower’s support for giant, smoothly paved roads. In 1919, he traveled with the military in a motor convoy across the country, from D.C. to San Francisco, in “the largest aggregation of motor vehicles ever started on a trip of such length,” the New York Times reported.

This was one of the first major cross-country road trips, and it planted the idea in Eisenhower’s mind that the federal government could and should make improving U.S. highways a priority. Soon, driving from coast to coast would become mythologized as one of the key American experiences. But in 1919, it was a terrible, torturous endeavor.

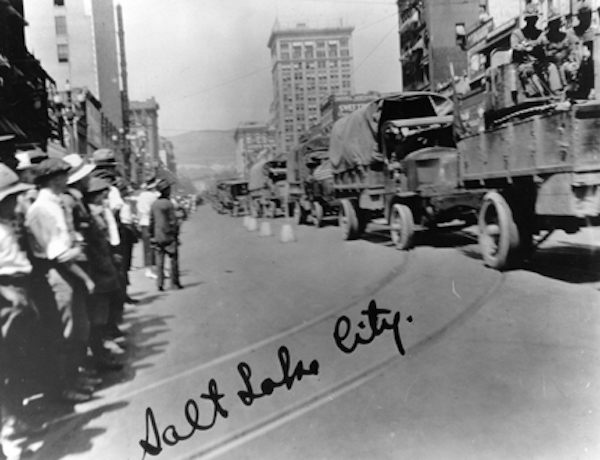

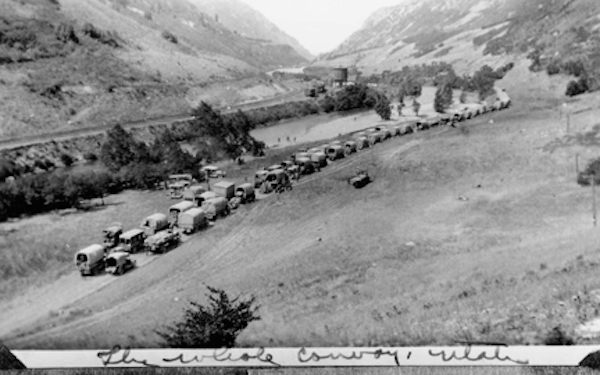

In 62 days, more than 80 trucks, cars and motorcycles made their way along the planned route of the Lincoln Highway, one of the first cross-country highways ever built. They crossed plains, mountains and deserts on roads that, up until Nebraska, were surprisingly well made. But once the convoy hit the West, the trucks started getting stuck in ditches, sand and mud, for hours at a time. By Utah, the conditions of the roads were so bad, it almost stopped the convoy altogether.

This was a pivotal point in the way Americans thought about the geography of their country. Traveling across the country was no longer a life-threatening ordeal–transcontinental railways had reached the Pacific in the mid-1800s, and in 1876, an express made it from New York to San Francisco in just 83 hours. But it wasn’t fun, either.

The idea of crossing the country on a lark was just taking hold: Eisenhower and a colleague joined the convoy at the last minute, basically because they thought it would be exciting. And the trip did immerse the military men in a cross-section of American life, at concerts, big city dances, chicken dinners, rodeos, barbecues, and ranch lunches. Most days, though, the reality of the road was less romantic: before the convoy reached California, its personnel would be forced to camp on twisty mountain roads, ration water and spend hours pushing their vehicles along otherwise impassable stretches. Like the oxen of western pioneers, the cars and trucks often died. But the mechanical beasts, at least, could be brought back to life.

In 1919, the military had just returned from the Great War in Europe, where War Department motor units had helped secure victory, and military leaders wanted to show their machines off. But any network of roads that these trucks might travel on was still, for the most part, imaginary. Since the late 19th century, the Good Roads Movement had been advocating for upgrades to the dirt and gravel tracks that connected cities to one another, and forming associations to finance and build them. One of the purposes of the 1919 convoy was to support this movement: a Zero Milestone marker would designate the spot from which it set off, in D.C.’s Lafayette Square, and in one early conception, that marker was to be decorated with a map of golden highways—the longed-for system of perfect American roads.

The route the convoy would take was mostly along the Lincoln Highway, the first major transcontinental motor route. The more than 80 vehicles carried 24 officers and 258 enlisted men, and they left D.C. at 1 p.m., on July 7, 1919. It took the convoy the rest of the day to reach Frederick, Maryland, where Eisenhower joined the group. In seven and a half hours, they had traveled 46 miles, a drive that today would take just about an hour.

From the very beginning of the drive, the convoy encountered problems. On that first afternoon, the convoy’s Trailmobile Kitchen broke a coupling, and an observation car broke a fan belt. The Militor wrecker winch, a towing vehicle, started work that first day. On the second day, the convoy was delayed for two hours, mostly due to wobbly bridges too dangerous to use or covered bridges that the trucks wouldn’t fit through. To avoid these, sometimes the convoy took a detour; sometimes it simply forded whatever body of water the bridge was meant to cross.

One truck was stuck in the mud. The roads, though, were excellent, according to the convoy’s daily log. They covered 62 miles, in 10 and half hours.

That pace—about 6 miles an hour—is what the convoy would average in its crawl across the country. No day was without difficulty, and though drivers had all claimed experience with trucks, Eisenhower’s impression was that they’d lied. “Most colored the air with expressions in starting and stopping that indicated a longer association with teams of horses than with internal combustion engines,” he later recalled.

For the first half of the trip, though, whatever car trouble the convoy had was “easily overcome,” young Lt. Col. Eisenhower would report. And while paved roads more or less disappeared between Indiana and California, the convoy stayed on schedule through Illinois and Iowa. It was in Nebraska that the trouble started.

Eisenhower’s report on this section of the trip is brief, but telling. “In Nebraska, the first real sand was encountered,” he wrote. “Two days were lost in western part of this state due to bad, sandy roads.” The convoy’s time in the state started out nicely enough: a number of vehicles were outfitted with new tires, the officers were allowed use of the “beautiful new Omaha Athletic Club,” and the Packard Motor Car Co. sponsored a dinner. The official observer even got to go up in a balloon.

But soon, as they pushed west, the roads started deteriorating. When it rained, the vehicles got stuck in soft spots on the roads, up to their hubs, and the men had to push them out. Outside of Lexington, the roads got so slippery that trucks started sliding into ditches by the side of the road. The Militor itself, up until this point the savior of all damaged and mired vehicles, skidded into a ditch, and it took two hours for the crew to extract it. On that day, 25 trucks in all skipped into the ditch. The next, all 12 engineers’ trucks needed to be towed at once. The Militor slid into a ditch again. The day after that, it took seven hours to pull all the trucks through 200 yards of quicksand.

This, though, was nothing compared to Utah. Out on the Salt Lake Deserts, the heavy trucks could barely pass through the tracks of sand and crystallized alkali. “From Orr’s Ranch, Utah, to Carson City, Nevada, the road is one succession of dust, ruts, pits and holes,” wrote Eisenhower. At points, the convoy was 20 miles from any source of water—and 90 miles from the nearest railroad. On August 21, the first day on the stretch that Eisenhower described, ten miles from their starting point, the convoy had to remove a sand drift: that took a whole hour. But that was the easy part of the day. Soon, the convoy had to leave its planned path, to detour around an impassable cut-off, and by 2 p.m., almost every vehicle they had was stuck in the sand. Getting them out “required almost superhuman efforts of entire personnel from 2 p.m. until after midnight,” the daily log reported. That day, the group went 15 miles—in seven and a half hours.

The next day, the convoy was running low on water. Each person got just one cup to last through supper and overnight. Fuel was running low, too, and so supper itself was cold baked beans and hard bread. Finally, a new supply of water showed up, having been brought from 12 miles away, by a team of horses. The entire team was exhausted, but because they were now behind schedule, their Sunday rest day was canceled. Finally, on Aug. 23, they made it through Utah and into Nevada, which wasn’t much better. It wasn’t until Sept. 3, after days more tedious progress, that they finally made it over the Sierra Nevada range and onto the “perfect roads” of California’s farmland, speeding through groves of peach, almond, orange and olive trees.

The convoy made it to San Francisco six days behind schedule. The trip, overall, was a triumph, and the governor of California threw a celebratory dinner featuring clam chowder, salmon, fried chicken, sweet potatoes, Turkish melon, and cigars. The commemorative program noted that it was impossible to think of the convoy without remembering the “hardship, privation, discouragement, and even death” that the Forty-Niners had gone through just a few decades before to accomplish the same goal. Traveling across the country was no longer such a crazy idea.

But by the end of the trip, the official observer reported later, “the officers of the Convoy were thoroughly convinced that all transcontinental highways should be constructed and maintained by the Federal Government.” As Eisenhower put it, “there was a great deal of sentiment for the improving of highways,” and on that point, “the trip was an undoubted success.”

At the time, the Townsend Highway Bill, which would create the first Federal Highway Commission, was under consideration in Congress, and the convoy’s experience would help convince legislators to pass it. It would be decades before America’s road system could actually ferry cars quickly across the country, and the real road trip era would begin. But this was a start.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook