Are These the Last Days of India’s Touring Tent Cinemas?

Once a major part of rural life, these traveling pictures shows were struggling even before the pandemic.

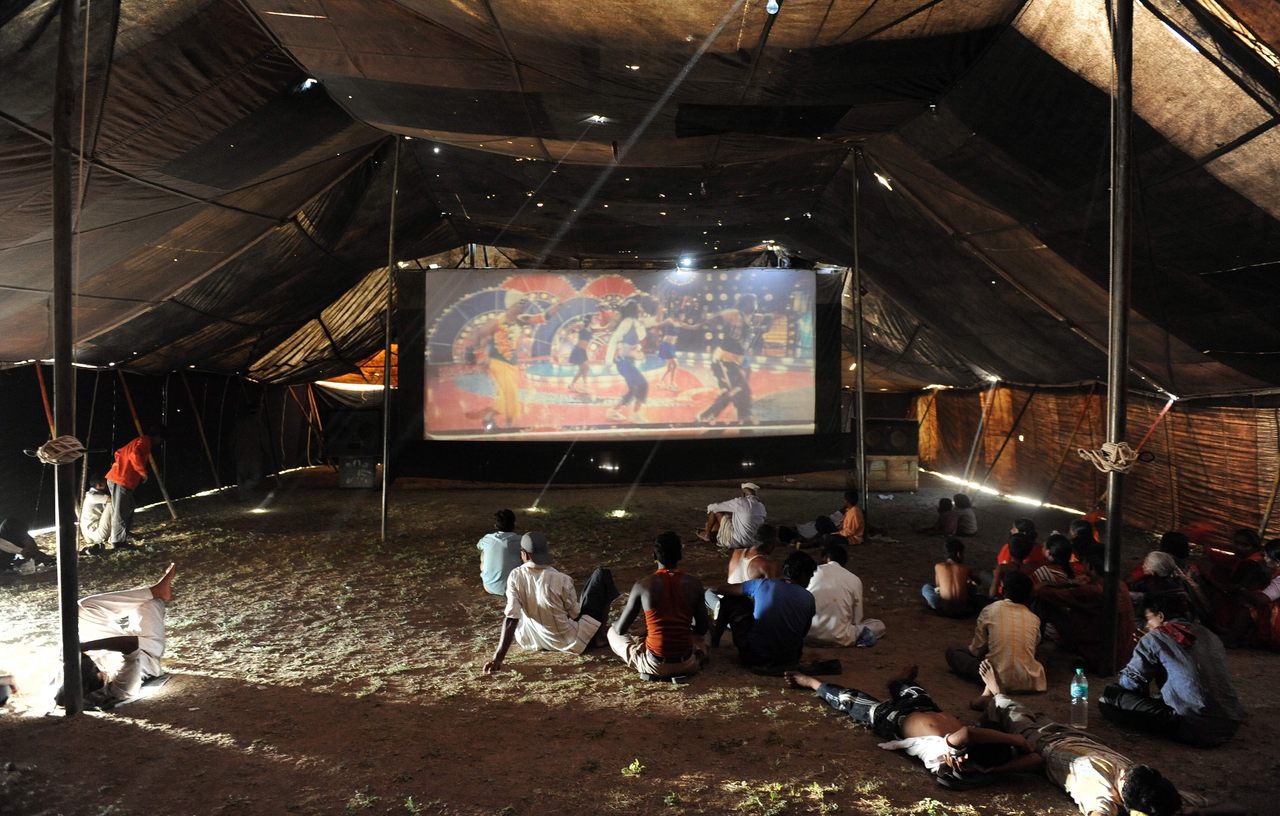

By the time the film reels arrive, the sky has darkened and the carnival is bathed in fairy lights. They’re late and everyone is waiting. Carrying them in a jute sack over his shoulder, a harried assistant weaves his way through the crowded fairgrounds and rushes into the largest attraction around: a roomy tent where hundreds have gathered to their dose of cinema for the day.

Jutting out of one end of the tent is a vintage green Ashok Leyland truck, its back converted into a projection room. The crowd had grown restless and angsty, with people loudly threatening to leave and demanding refund of the Rs. 30 ($0.40) tickets. The arrival of the reels brings a wave of relief to the anxious crew and the owner of Sumedh Talkies, the zesty and pragmatic Muhammed Navrangi, who’ll go to great lengths to keep his business afloat—including playing a sleazier flick or two to reel in the bucks.

The spools are carefully loaded on a clunky 35mm projector that creaks with a half-century of age. One wrong move and the entire system could collapse into another of its frequent breakdowns. A quick ritual for luck and appreciation: a coconut is broken on the ground and incense waved in the air. For the Sumedh Talkies, cinema is sacred. It feeds and clothes the crew.

The screen springs to life with the 2013 Hindi action flick Himmatwala. The audience, crouched on the pebbled ground is shushed into silence, eyes glued to the screen. There’s song, dance, drama. This comes from a scene in the 2016 Cannes award-winning documentary The Cinema Travellers, which elegantly captures the spirit of India’s long-standing but disappearing traveling cinema culture.

The digital revolution, as it filtered into the countryside, gradually made the business of taking film on the road unsustainable. From more than 1,000 traveling talkies in the western Indian state of Maharashtra alone, where much of the tradition was concentrated, numbers have fallen to just 50 today. The pandemic has dealt a fresh blow, with lockdowns bringing fairs and touring cinemas to a complete halt. The talkie owners who haven’t yet fully closed down are caught between a deep sense of nostalgia, a lack of opportunities to move on to other businesses, and restlessly holding out hope for a revival.

The long and colorful tradition of traveling movie theaters in India dates back to the 1950s. Over the years, these operations made the rounds of the annual festival of village carnivals known as jatra, meaning “journey.”

During the eight months of jatra, dozens of touring talkies traveled from village to village, trucks loaded with equipment, including tents and screens to play films in Hindi and Marathi, the local language. Each tent took two to three days to set up for a crew of 10 to 20 men of varying ages and skill, who then slept off the long days’ work in the tents. After a few weeks in one location, the crew would pack up and head to the next village, at least until the monsoons ended the festival season and sent everyone home.

This tradition brought motion pictures to regions without permanent cinemas, and were a fixture on the cultural map of small-town India. The traveling talkies were originally conceived by men who had left their villages for the cities and wanted to bring the cinema magic they found there back home, says Shirley Abraham, codirector of The Cinema Travellers. “They brought back the rejects of the city, the older projectors and prints, to annual religious fairs, where there was a ready audience, mostly male at the time,” she says. “They started to embed themselves into this religious tradition. Over time, the traveling cinemas became the mainstay of the fairs.”

Anup Jagdale, 38, owner of Anup Talkies, practically grew up in his father’s cinema tents. “They were the golden years of the touring cinemas. All my memories are tied to the movies of the 1980s and 90s that played in our tents, featuring stars like Amitabh Bacchhan and Mithun Chakraborty. My father set up the business in the 50s and I inherited it when he was paralyzed in an accident when I was 22,” says Jagdale, who lives in Satara district in the state.

“It was a different time and a different ambience. There would be thousands in the audience. In the colder months of December and January, people would bring blankets and camp in the tents, watching movies all night. They were the original multiplex, you know, about 10 tents on each carnival ground showing different films,” he says.

But those days are over, he adds. If there’s anything left, it’s a truncated version. Before the pandemic began, Jagdale’s days still had a somewhat predictable rhythm: eight months on the road, through the gentle, rolling hills and golden-hued dusty plains of rural Kolhapur, Sangli, and Sholapur. Any profit was gone, but he was able to survive. A couple of sponsorships from tech companies helped, which offered him logistical support to hold digital screenings. His business even became the subject of a 2017 documentary, A Tent, a Truck & Talkies, by Sujit K. Jha, that traced its decline.

“From the days when carnivals would have a dozen cinema tents, we are down to one or two. I think this is the climax for tent cinema. I am tired and heavily in debt,” Jagdale says. “The last time I went on tour before the pandemic hit, we had to cut the tour short to three months. It’s been hard to find prints after 2011 when the production labs shut down. The days of the 85-year-old projector that my father had bought are over. I can’t afford a digital setup, which costs nearly half a million rupees [$7,000].”

As mobile entertainment and cheap internet have flooded rural homes, and the cost of equipment and films has risen, talkie owners such as Jagdale and the Nashik-based Sanjay Dhadwe, 43, have few options. Dhadwe, who is also a part-time actor and gets by on occasional television and film roles, was still on the road with his Pushpanjali and Abhayraj Talkies before the pandemic brought things to a standstill. “In the last two decades, I have taken my talkies to 130 remote corners of Western Maharashtra, covering 15 to 16 villages in each season,” he says. “I have moved from analog to digital. But that hasn’t particularly helped, as now there are so many ways to watch a film even in the villages. New films are released on television within months. That’s caused a serious blow to us.”

“As we followed the touring cinemas over five to six years, we saw the audiences thinning out,” says Amit Madheshiya, codirector of The Cinema Travellers. “Earlier, there would be people on both sides of the screen, due to lack of space. That gradually changed.”

Even though they know the future is unlikely to bring significant change, some owners hold out hope for a revival. Muhammed Navrangi in Buldhana, for example, was an early adopter of a digital projection system. He is putting all his energy into sprucing up his business through loans, swapping the old for new in the hope that higher-quality screenings will bring people back to tent cinema. “The audience will realize that though they have entertainment on the television, it’s not the same as watching as a community,” he says.

Though he can’t afford a digital system, Jagdale is looking at new, inflatable, waterproof tents that can be set up in just a few hours, have modern amenities such as air conditioning and better sound systems, a red carpet, and a “new age multiplex” feel. He has also spent the past year writing a memoir about traveling talkies culture: “I don’t know what will happen in the future, but I have to hold on to the memories and the stories I have heard from my father.”

In recent months, a half-dozen talkie owners, including Jagdale, Navrangi, and Dhadwe decided to band together to revive the Maharashtra Touring Talkies Union, and sought a meeting with the Maharashtra Cultural Affairs Minister, Amit V. Deshmukh in Mumbai. Niraj Kamble, 51, the Buldhana-based owner of Anand Touring Talkies and president of the union, says they were promised support to preserve the tradition as living heritage, including grants to promote the arts, subsidized electricity, interest-free loans, pension schemes, and more. “Things are so dire that I started selling vegetables to make ends meet in the past year. I was midway through a tour when the lockdown happened and I had to pack up and move back home. The audience had anyway dwindled to 20 to 50 per show,” says Kamble. “We live on the energy of the public. If we manage to get the state aid that has been promised, I would like to do a complete makeover and see if we can revive the tradition.”

At the moment, touring talkies are issued licenses to operate in communities with less than 100,000 inhabitants. Director of Cultural Affairs Ravi Bibhishan Chavare says there are efforts to revise this policy to expand their reach to locations with bigger audiences. “Even though the audience has shrunk, they still serve a purpose as many regions still do not have permanent cinemas,” he says.

As the showmen wait for better days, and another wave of Covid-19 begins to ebb, they have begun to plan for the jatra season. Though he has had to sell equipment and lay off half his crew, Dhadwe says he still has passion for bringing cinema to the villages. “This world is all I have. How can I give it up?” he says. “There is great joy in bringing happiness to the audience through a film. Despite the problems, tent cinema remains the pride and centerpiece of the fairs.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook