A Centuries-Old Frieze, Newly Deciphered, Tells the Story of the End of the Bronze Age

A great prince, an almost-forgotten ancient script, and whisperings of a forgery.

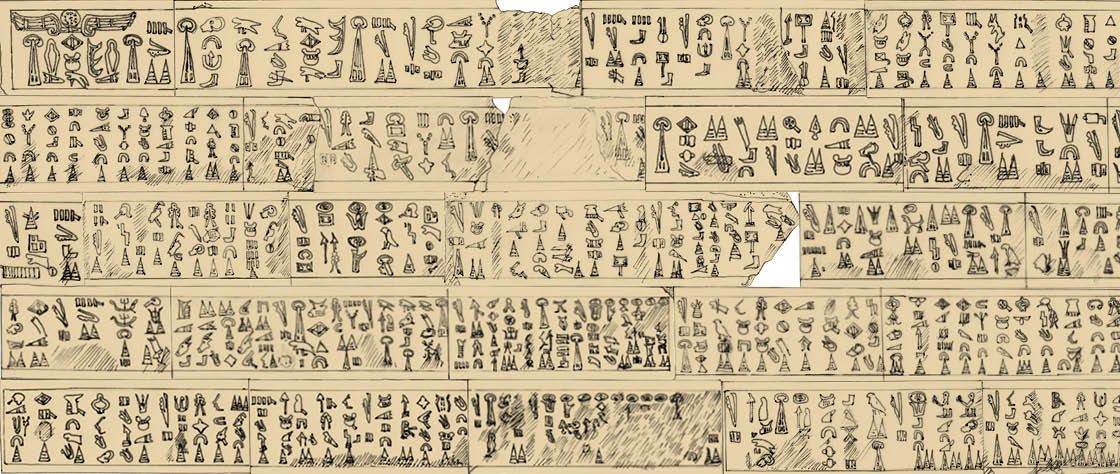

A limestone slab, 31 yards long, may have related the story of the end of the Bronze Age. An interdisciplinary team of Swiss and Dutch archaeologists have now deciphered the symbols thought to have adorned the frieze, almost 150 years after it was discovered and summarily destroyed. In 1878, villagers in Beyköy, a tiny hamlet in western Turkey, found the large, mysterious artifact in pieces in the ground, and saw that it was engraved with seemingly illegible pictograms and scribbles. It would be 70 years before that language, now known to be millennia-old Luwian, could be read by scholars.

According to Eberhard Zangger, the president of a nonprofit foundation called Luwian Studies, the symbols tell stories of wars, invasions, and battles waged by a great prince, Muksus. Muksus hailed from the kingdom of Mira, which controlled Troy 3,200 years ago. The inscription describes his military advance all the way through the Levant to the borders of Egypt, and how his armies invaded cities and built fortresses as they went. Such invasions from the east are thought to be among the causes of the collapse of the Late Bronze Age.

But these tales were very nearly consigned to oblivion. After the slabs were found in the 19th century, French archaeologist Georges Perrot painstakingly copied out every symbol—before the stone was used to build the local mosque. Accompanying bronze tablets, similarly inscribed, were found soon after by Turkish authorities, and have not been seen since. Later, Turkish scholar Bahadır Alkım found and copied Perrot’s reproduction. That version, too, seems to have been lost, until yet another copy of it was found in the estate of James Mellaart, a famous archaeologist who died in 2012. His notes explain how the frieze had been discovered and the copies made, and the work he had done on it. Mellaart’s son passed the documents on to Zangger.

Barely two dozen people in the world can read Luwian. Fred Woudhuizen, an independent scholar near Amsterdam, is one of them. Working with Zangger, he deciphered the inscription, and the team has now assembled a transcription, a translation, a detailed commentary, and the remarkable research history of the find. Their work will be published in December in TALANTA – Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. Zangger has also recently published a book about the frieze in German, Die Luwier und der Trojanische Krieg – Eine Forschungsgeschichte (roughly translated as The Luwians and the Trojan War – A Research History)

Luwian, closely related to Hittite, has around 520 symbols—a mixture of pictograms representing individual words such as bird, cow, and hand, and phonetic syllabograms that represent sounds. Beginning in the 1950s, a team of Turkish and American experts worked on translations of Luwian writings, but the publication of their findings kept being delayed and delayed until, by 30 years later, nearly everyone involved had died. Only Mellaart was left—and he could not read Luwian.

The work has sparked concerns from scholars not involved in the research, who suggest that the frieze and, in turn, stories it is thought to have contained, could be a forgery, reports Live Science. Until records of the inscription are found outside of Mellaart’s notes, some say, it will be hard to confirm the age and authenticity of its contents. That said, an inscription that length (31 yards!) would be near-impossible to forge, say Zangger and Woudhuizen, especially given that Mellaart could neither read nor write the ancient script. In the meantime, this poorly understood corner of ancient history is finally getting a moment in the sun.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook