The People Who Decide What the Inside of a Human Body Sounds Like

Our brains don’t really crackle and hiss, but on film and TV shows, they must.

Quick—what does a brain sound like?

Time’s up! The answer is, of course, “nothing.” If you said “lightning and sparks,” though, you’re forgiven. Odds are good that every “trip” you’ve taken inside the brain has featured a CGI image of squiggly gray matter, accompanied by the sizzling sound of electricity.

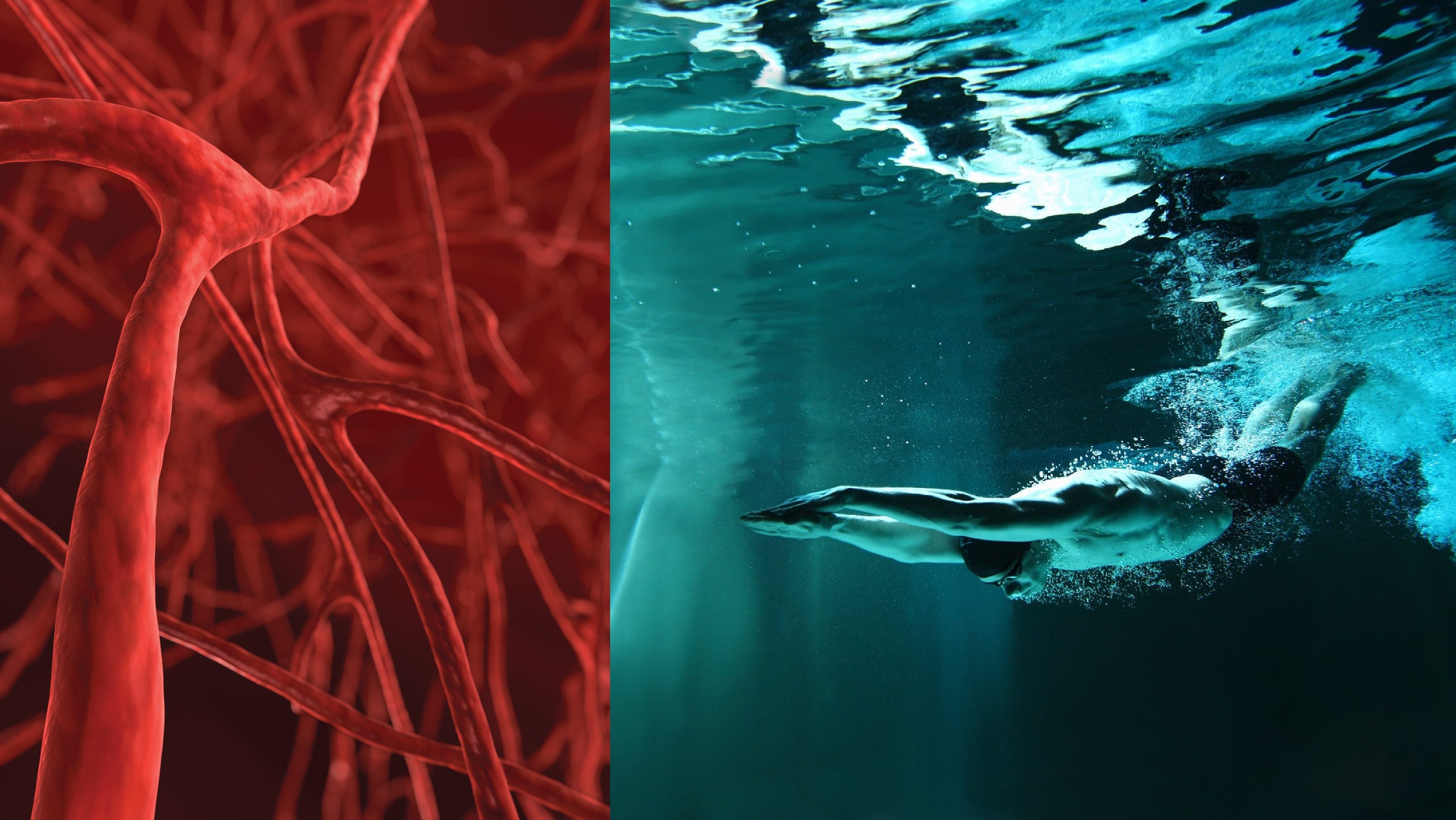

This and other sonic clichés—blood whooshing through veins, organs squishing and pulsing—are as much a part of a certain type of hour-long TV drama as a plot twist before a commercial break. They’re also a staple in documentaries, where such sounds accompany visuals depicting smaller dramas, like the journey of a blood cell, or the ravages of puberty.

The professionals who add sound to these environments have the difficult job of taking us inside the human body, a place both intimately familiar and almost impossible to access. So where do they get their auditory touchstones? And how do they keep them fresh—or, at least, fresher than the corpses they’re sometimes asked to soundtrack?

For many film and television sound designers, the first step involves diving right in—literally. “I start, sonically, underwater,” says Michael Babcock, who has taken viewers inside bodies for several TV shows, including Preacher and Limitless. He traces this approach back to his childhood, when a Walt Disney documentary taught him that the human body is mostly water. “I imagine what things sound like in a pool or an ocean, or even a bathtub under the water line,” he says. He then recreates those effects in his studio.

Chad J. Hughes, who was the assistant sound designer for over 100 episodes of CSI, concurs. “Any time you remove outside noise that involves air hitting the eardrum”—for instance, by dunking your head underwater—“it can give you the sensation of what it’s like inside of a body… those gurgling sounds,” he says. Hughes says he’s used an underwater microphone to record people swimming, and then used that to simulate the sound of blood flowing through a vein.

Other times, he records props on dry land and tweaks them with effects. “Anything that squishes, or makes an organic kind of noise—you can take a sound like that, pitch it way down, slow it down, and roll the high frequencies off,” he says. “It then gives you that sense of muted, fluid motion.” (Squishy objects, like raw chickens or hair gel, are especially helpful for digestion scenes: for the IMAX film The Human Body, Anthony Faust and Kenny Clark recorded themselves stirring around a mixture of wallpaper paste and spaghetti.)

A supercut of scenes depicting bodily processes—like hair growing or cells dying—gathered by Svein Hoier.

More familiar sounds, such as gurgling stomachs or gushing blood, are one thing. But what if the camera travels somewhere less accessible—inside the brain, for instance? Svein Hoier, an associate professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, recently analyzed hundreds of “inside the body” scenes from popular educational miniseries, crime shows, and medical dramas produced over the past two decades, and published his results in The New Soundtrack.

Every CGI brain he came across, in documentaries and fictional shows alike, made the same type of noise: a crackling, electric hiss. “Visuals that show the firing of neurons are combined with sound effects connected to the various sounds of electricity,” he writes. (Hoier traces this convention back to a particular episode of Body Stories, an educational anatomy show that aired on the Discovery Channel in the late 1990s.)

Hoier found that many more outwardly silent bodily activities had acquired standard sound effects, too. In films and TV shows, straining muscles squeak against each other, intestinal valves smack open and shut, and dying brain cells “pop” out of existence. When strands of hair grow, they sound like creaking sailboat ropes, or trees bending in a windstorm. Even though viewers know these sounds are invented, they generally don’t question them. “[There is an] understanding of such sounds being illustrative rather than documenting the inside of bodies,” says Hoier. The use of CGI, rather than live-action film, helps with this separation.

But how do sound designers come up with them in the first place—and why is there such unity across genres? According to Hughes and Babcock, those decisions are mostly based on the infrastructural makeup of the body, and the idea that, as the camera zooms through this environment, it’s encountering different materials. “If there’s a bone, we’re going to hear cracking,” says Hughes. “If it’s something like an organ, it’s going to be coddled, given some movement.”

Having baseline sounds that conform to viewer expectations also gives designers raw materials with which to craft drama and emotion. On the show Preacher, which follows a priest possessed by a devil and features scenes in which the camera travels from a ”demonic” heart up through the esophagus, “the challenge was to make the sound [go with] the violence of the visual,” says Babcock. What did this usually sound like? “Heartbeats topped with explosions,” he says.

A supercut of CGI “brain scenes,” compiled by Hoier.

The many creative deaths of the CSI franchise make for a series of auditory challenges. In one episode, Hughes says, the camera zooms in on its first victim, a very burned body. “When we’re close to the body, we’re hearing more practical elements like the crackling and the charring,” he says. “Very subtle, but we’re selling that this body has been overcooked.” If they had gone even further in, he might have replaced the standard underwater plunge with the sound of a volcano. “Maybe a low rumble, with charred embers simmering,” he imagines.

It may be gruesome, but to its practitioners, it’s an art. “We ask, ‘What is the story trying to tell at that moment?’” says Hughes. “Then we come in with our set of tools.” Those tools just happen to be underwater microphones, volcano recordings, and giant bags of paste and spaghetti—the craziest parts of the outside world, used to bring us inside ourselves.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook