The Very Real Search for the Bible’s Mythical Manna

Scholars, soldiers, and scientists have long puzzled over the supernatural substance.

When the Israelites escape the pharaoh’s army in the Book of Exodus, they are left to wander the desert, half-starving. What is the point of leaving Egypt, they ask themselves, only to perish from hunger in the wilderness? Could dying in freedom really be preferable to living in chains? According to the text, God addresses Moses during this discord, telling him, “Behold, I will rain bread from heaven for you.” The next day, “upon the face of the wilderness there lay a small round thing, as small as the hoar frost on the ground.”

Manna, the heaven-sent food said to have sustained the Israelites for 40 years, has long captured the imagination of scholars, soldiers, and scientists alike. Many have mined biblical verses for clues about the Old Testament substance. Adding to the puzzle are the other descriptions of the food in the Bible: on hot days, manna melted in the sun. If not gathered quickly enough, it rotted and bred worms. In Exodus, it’s referred to as “like coriander seed, white,” with a taste “like wafers made with honey.” Numbers, on the other hand, likens the flavor to “fresh oil” and describes how the Israelites “ground it in mills, or beat it in a mortar, and baked it in pans, and made cakes of it.”

In addition to this list of traits and possible culinary applications, manna also had seemingly supernatural qualities as well. It spontaneously regenerated each morning, even in convenient double quantities on the day before the sabbath. According to the Jewish mystical treatise known as the Zohar, the consumption of manna imparted sacred knowledge of the divine. Another Jewish text, The Book of Wisdom, even claims that the flavor of manna magically changed according to the tastes of the person who ate it.

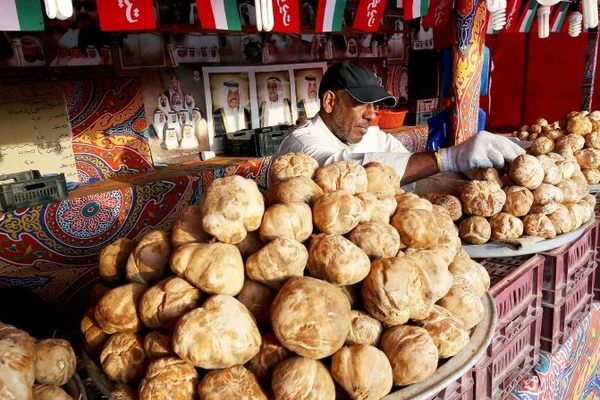

Commentary on manna is not exclusive to the Jewish tradition. In the New Testament, manna is mentioned in both the Gospel of John and the Book of Revelation. In a sermon delivered shortly after the Feeding of the Five Thousand, Jesus compares God’s gift of body-nourishing manna to his own ability to eternally nourish the soul: “I am the living bread which came down from heaven: if any man eat of this bread, he shall live for ever.” References to manna are also present in Islamic texts: one Hadith passage has the prophet Muhammad likening desert truffles to manna.

Moses and his followers were apparently befuddled by their strange foodstuff. Exodus relates that they “wist [knew] not what it was” that they were eating. As for what the Israelites said upon first beholding their heavenly sustenance, translators and scholars are deeply divided. The King James Bible renders the phrase “man hu” as “this is manna.” Others parse the Israelites’ words as “This is a gift.” Still others have the Israelites reacting with a quizzical “What is this?”—a confusion that would be shared by those who later endeavored to figure out what manna could be.

Over the years, a number of scientists have also attempted to pin down a real-world analogue for manna. For some, like Israeli entomologist Shimon Fritz Bodenheimer, such an activity was an opportunity to use ancient sources to glean information about little-studied natural phenomena. Biologist Roger S. Wotton, whose study “What Was Manna?” runs through the varied theories surrounding the supernatural substance, believed that the exercise could lead to a more skeptical reading of the Bible.

The ideas advanced by scholars over the years vary as widely as their motivations. In their book Plants of the Bible, botanists Harold and Alma Moldenke argue that there were several kinds of food collectively known as manna. One of these, they posit, is a swift-growing algae (from the genus Nostoc) known to carpet the desert floor in Sinai when enough dew on the ground allowed it to grow. The Moldenkes also make the case that a number of lichen species (Lecanora affinus, L. esculenta, and L. fruticulosa) native to the Middle East have been known to shrivel up and travel tumbleweed-like on the wind, or even “rain down” when dry. Nomadic pastoralists, they report, use the lichen to make a type of bread.

The lichen theory, the Moldenkes argue, would explain both how the Israelites prepared their manna and why they might have spoken of it as having fallen from heaven. A multi-decade diet exclusively of algae or lichen would certainly explain why the Israelites complain bitterly that the lack of normal food had left them feeling like their very souls had dried away. Cambridge historian R.A. Donkin also notes that L. esculenta was used in the Arab world as a medicine, an additive to honey wine, and a fermentation agent.

The idea of a desert-growing food also had a military application. According to Donkin, the troops of Alexander the Great might have staved off starvation by eating L. esculenta while on campaign. French forces stationed in Algeria in the 19th century experimented with lichen, their candidate for biblical manna. They hoped that a readily available desert foodstuff as a source of nutrition for soldiers and horses in arid areas could allow for the consolidation of colonial power.

Poking a hole in the lichen theory, however, is the fact that L. esculenta, one of the most commonly cited possibilities for a “manna lichen,” doesn’t grow in Sinai. Instead, the current frontrunner in the manna quest is not lichen or algae but a type of sticky secretion found on common desert plants. Insects that rest on the bark of certain shrubs leave behind a substance that can solidify into pearl-like, sweet-tasting globules. Often referred to as manna, this secretion has both culinary and medicinal uses. In Iranian traditional medicine, one variety is used as a treatment for neonatal jaundice. In his 1947 article “The Manna of Sinai,” Bodenheimer floats the theory that this substance may have been what the ancient Israelites ate as well. He also identifies the species of scale insects and plant lice whose larvae and females produce the so-called “honeydew.”

In recent times, some have gone past trying to pinpoint what manna might be and attempted to taste the biblical food for themselves. Last summer, the Washington Post reported on D.C. chef Todd Gray’s quest to make manna the next big trend in haute cuisine. The manna that Gray and other chefs such as Wylie Dufresne use is a sweet resin imported from Iran that sells for $35 an ounce. But stringent trade sanctions placed upon Iran in recent years have forced Gray to improvise his own ersatz versions (one substitute manna blended sumac, sesame seeds, and fennel pollen). Such legal hurdles add yet another layer of inaccessibility to a substance wondered over and quested after for millennia.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook