Is This the First Time Anyone Printed, ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’?

Ironically, the early computing phrase’s history is rife with bad information.

An IBM punch card reader. (Photo: Joi Ito/desaturated from original/CC BY 2.0)

In March of 1963, a young AP reporter named Raymond J. Crowley visited an IRS processing facility in Martinsburg, West Virginia. There, as recorded in his dispatch of April 1st, Crowley met a computer (“a robot without any feelings”), hit on a young woman (“a secretary, a looker”), and heard a catchy phrase: “Garbage in, garbage out.”

Or GIGO, for short. Crowley’s report is thought to be the first time the phrase had made it into print, but for years prior computer operators had invoked the truism whenever applicable. Did you mispunch a hole while writing your first FORTRAN program? Got yourself a case of GIGO. Did you mistranscribe a crucial bit of math, turning the 1962 Mariner I satellite into an $18 million piece of exploded space junk? GIGO. Was your 1963 tax refund incorrect due to a data entry error at the processing facility in Martinsburg, WV? GIGO.

But Crowley’s citation might not be the first official record of the now-famous phrase, one of early computing’s first breakout moments. The answer itself is a lesson in separating the good information from the bad.

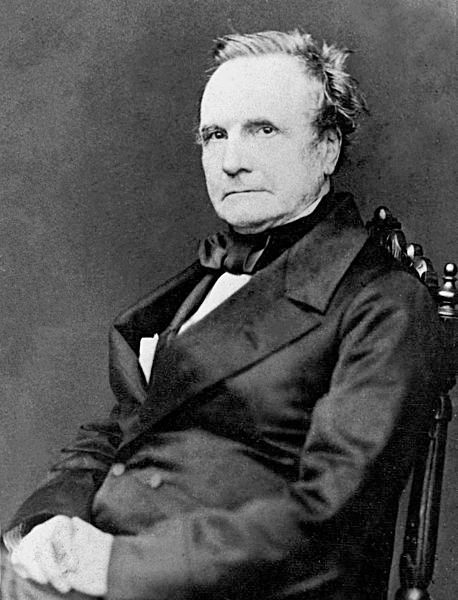

Charles Babbage, 1860. (Photo: Public Domain)

The idea behind GIGO actually dates to the very dawn of computation, the early 19th century, when Charles Babbage presented the design for his “difference engine” to England’s Parliament. Recounting an early encounter with some members of that body, he wrote: “On two occasions I have been asked,— ‘Pray, Mr. Babbage, if you put into the machine wrong figures, will the right answers come out?’ I am not able rightly to apprehend the kind of confusion of ideas that could provoke such a question.” No doubt he could’ve used some terse expression to convey his frustration.

When GIGO was coined, a century later, computers were still quite physical. Three years after Crowley’s visit, a film crew came to Martinsburg to record the futuristic tax processing done there. Their footage—which resulted in a 10-minute short titled Right on the Button—documented the operation in vivid color.

Computers the size of washing machines blink and buzz; gigantic tape machines spin at odd intervals; a room full of women pound on number keys to make punch cards; men in skinny ties pile those cards into card readers. And unlike the corrupted files we drag to a trash can icon today, “garbage” in the computing world of 1966 was the real deal: trash cans full of punch cards, piles of corrupted magnetic tape.

Soon the novel phrase, compact and generic, escaped computation and entered the general lexicon, where it became mildly pejorative. Teens became a particular focus of GIGO-isms, since they were always consuming junk food, reading junk magazines, listening to junk music, obsessed with junk hobbies.

The ultimate example, though, might be the phrase’s Wikipedia article. On August 2, 2007, a Connecticut IP address made an anonymous contribution to the page’s opening paragraph:

“The expression Garbagein/Garbageout was initiated as a teaching mantra by George Fuechsel, IBM 305 RAMAC techician/Instructor, later to evolve into the aphorism GIGO. [sic]”

Within a week someone had come by and fixed a few typos. Within a month, someone had annotated the claim as “Citation needed.” Three years later a print book appeared, in its second edition, confirming that Fuechsel had indeed coined the term, and that he was an IBM 305 RAMAC instructor. In 2011 that book was added as a footnote to the Wikipedia page. Citation no longer needed. And now, nine years after the original edit, at least five books tell a similar story, often at great length, and with minor embellishments.

But even that fact has grey areas. In 2004, George Fuechsel posted a comment on a blog entry that discussed the history of GIGO. He wrote that sometime in 1958 or 1959 he had come up with the phrase while teaching a course on the 305 RAMAC for IBM customers in New York.

IBM 711 card reader on an IBM 704 computer at NASA, 1957. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

But Fuechsel did not comment in order to stake a claim. “Since that time,” he wrote, “I have believed, and asked friends and family to believe, that I coined the phrase. Did I?”

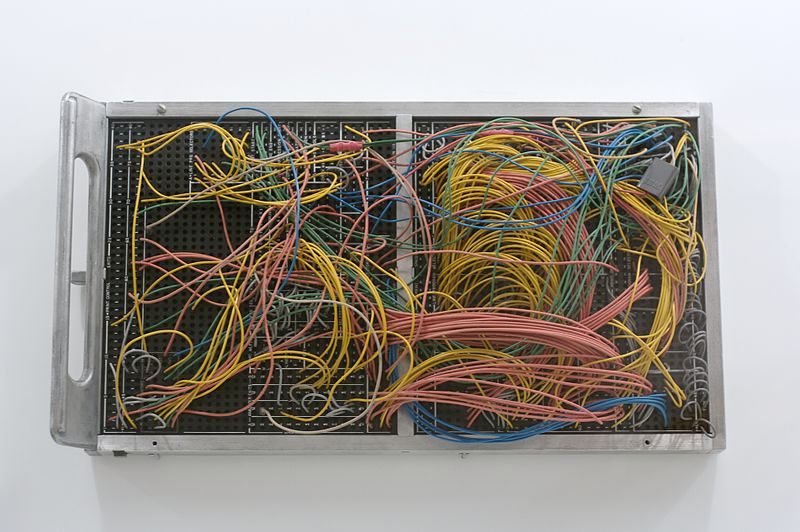

Though much about the IBM 305 RAMAC was beautiful—one part was a tall cylinder full of huge spinning ochre discs—it spoke a crude machine dialect, nothing like higher-level programming languages of today, or even ones available a few years later. In his time as an instructor, Fuechsel must have seen those trainees feed the 305 a lot of garbage. No doubt the trainees expected, like the confused Lords who heard Babbage explain his difference engine, that some non-garbage might come out.

In our modern era of computing, GIGO has lost its frequency in programmers’ vernacular. Autocorrect has reduced the garbage load, for instance, although this technology often inverts the problem, opting for overcorrection rather than under. As more facts fill computers and algorithms improve, that class of mistakes will start to disappear.

An IBM 305 RAMAC. (Photo: Public Domain)

One major source of good-facts-in, good-facts-out: optical character recognition (OCR) technology, which is advancing all the time, turning long dead newspapers into readable, searchable knowledge. Which might explain why Wikipedia thinks Raymond Crowley’s 1963 report on an IRS robot was the first to record, in print, “Garbage in, garbage out.”

But had you sat down with the Times Daily of Hammond, Indiana on November 10, 1957 (and persevered all the way to page 65), you would know otherwise. There, on the page’s upper-right, you would have found an article that opened with a bang: “BIZMAC UNIVAC, GARBAGE IN-GARBAGE OUT — all new terms in the Army… These colorful expressions are part of the working vocabulary of the military mathematicians who man the Army’s electronic computors [sic].”

The control panel for a 1950 IBM 305 RAMAC, (Photo: Marcin Wichary/CC BY 2.0)

I found this by searching the term in newspaper databases; as far as I know, this correction to the official record hasn’t been published before.

This story shows that six years prior to Crowley’s failed seduction, and one year prior to Fuechsel’s IBM 305 training courses, an army computer specialist William D. Mellin and his work with “mechanical brains” had been using the phrase.

“Did the results meet the original requirements or should the problem be rerun with corrections?,” the article asks, paraphrasing Specialist Mellin. “That’s where ‘Garbage in, Garbage out’ (GIGO) enters the vocabulary.”

But Mellin did not claim to invent the term, either, and my searches of military databases yielded no hits. So it’s a return to anonymity for GIGO, a linguistic powerhouse forever searching for the correct input.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook