The Student Yearbooks of a Japanese-American Detention Camp

Topaz operated like any other 1940s U.S. high school, except its teenagers were prisoners of the federal government.

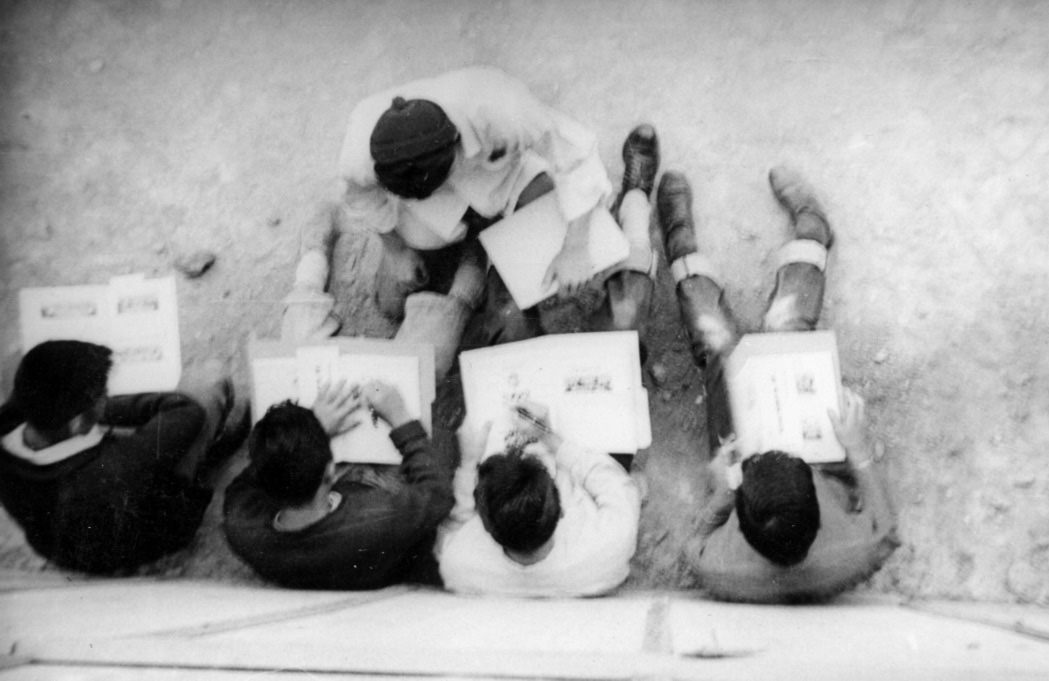

As a historical tool, high-school yearbooks provide a great deal of insight into youth in all its awkwardness and heightened emotions.

For the alumni of Topaz High School in Delta, Utah, those feelings are more than complicated.

On February 19, 1942, two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which created a “military exclusion area” on the west coast of the United States, forcing about 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry into incarceration camps for the rest of World War II.

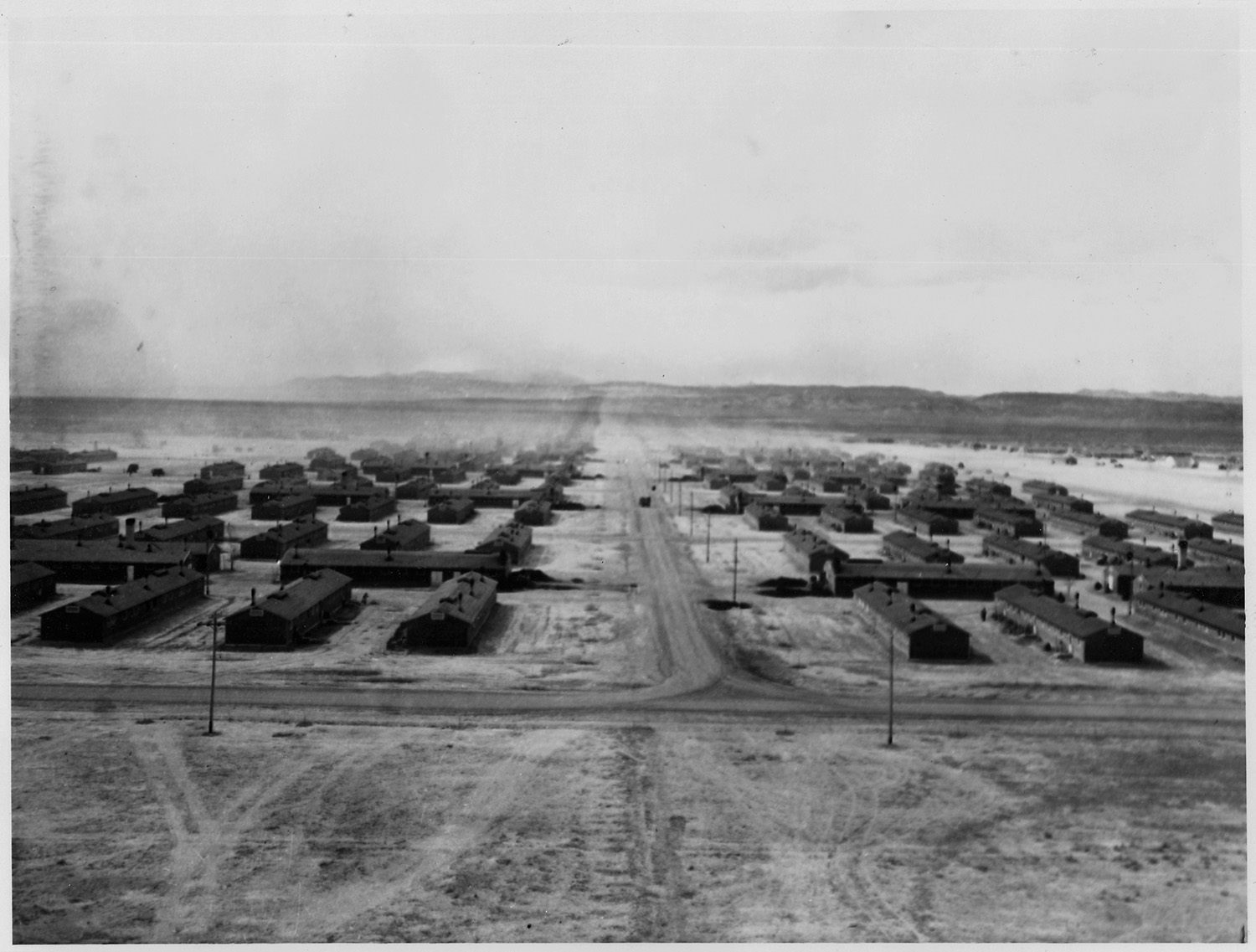

One of these sites was located in rural Delta, Utah. Opened in September 1942, it was called the Topaz Internment Camp, or Topaz for short.

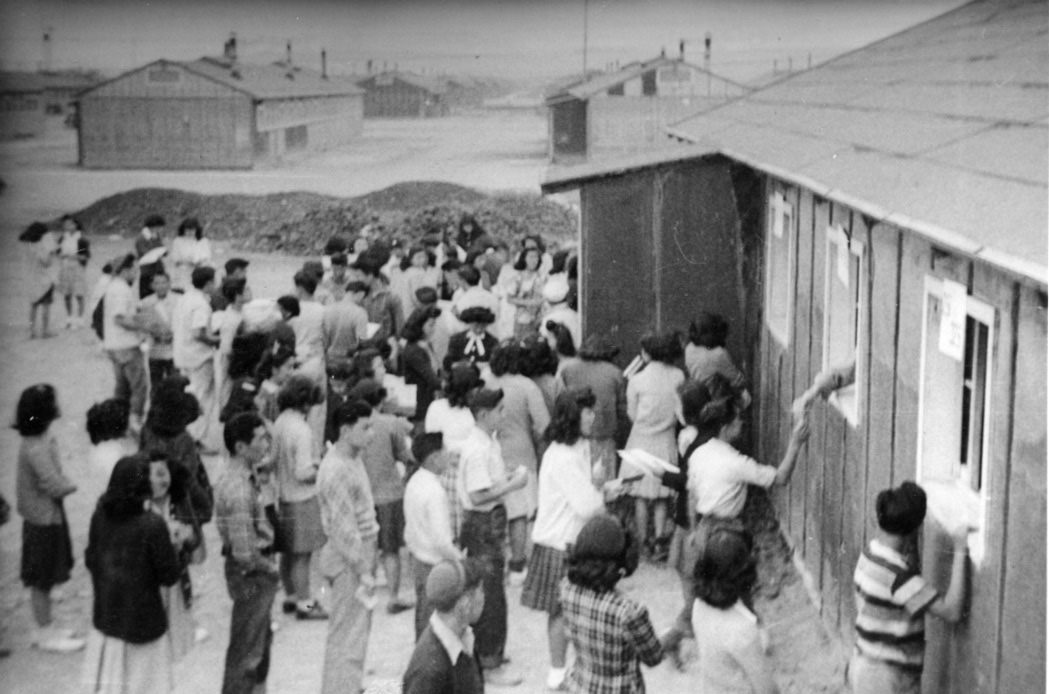

Topaz held so many prisoners that it became Utah’s fifth-largest city during World War II, nearly four times larger than the better-known Manazar camp in California. The population swelled so much (around 8,300 people at its height) that the Buddhist Churches of America, or the B.C.A., relocated their headquarters to Topaz. The camp boasted a sizable number of school-aged children. Two elementary schools, a junior high, and a high school all served as major parts of the community.

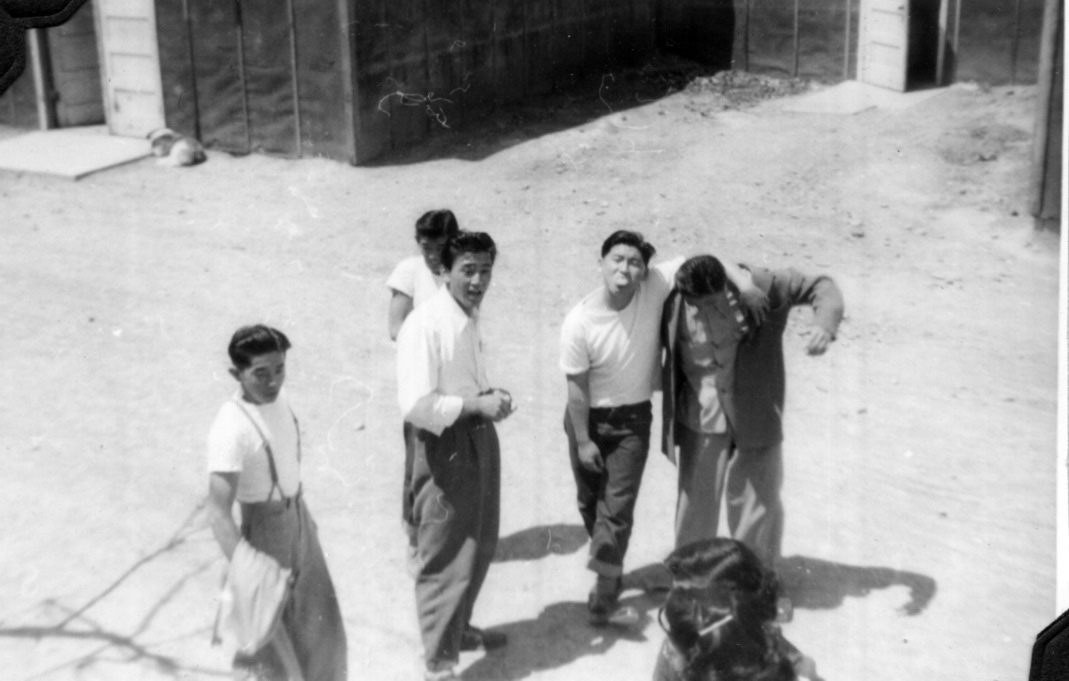

Between 1942 and 1945, several Japanese-American high-school students attended Topaz High School, an institution created specifically for them. Taken from their homes, imprisoned by the U.S. government, and placed in a completely unfamiliar environment, they recorded in their yearbooks a unique version of the typical American high-school experience.

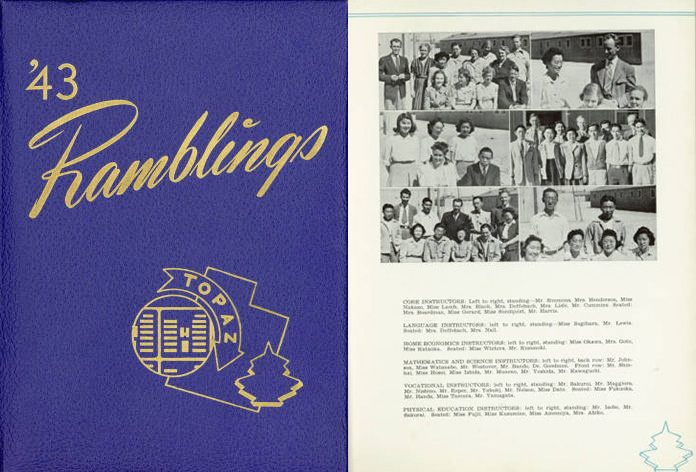

Utah State University has archived the 1943 and 1944 editions of the Topaz High School Ramblings yearbook. With a cursory browse, the Topaz High Rams look just like any other 1940s high school students. They played sports, printed alma mater lyrics that probably nobody knew by heart, and produced a slick-looking literary magazine. Topaz High was a prison camp school for unjustly incarcerated Americans, but the yearbooks provide the perception of normalcy.

In the 1943 Ramblings, the beginning dedication reads, “This year finds us vastly different from our naive selves of previous years.” Alongside photos of students, the old high schools they attended, mostly in California and Washington, are listed directly above their Topaz High School activities.

Modern educators and social service workers repeatedly say that kids are resilient when faced with difficult situations. The Ramblings attest to this sentiment. Most of the students in the yearbook photos look bright-eyed, ready to face their future. Others seem awkward and not wanting to be at school. Despite clothing rations of the time, the students look their best for Picture Day.

Some spreads in the Ramblings allude to intense patriotism. The senior superlative page (which includes the category “Brainiest of the Brainer Girls”) is entitled “So Proudly We Hail!” This is taken from a line in the Star Spangled Banner.

Throughout the Ramblings, references to the student body’s love of the United States abound. In fact, several detainees contributed to the Allied cause or served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II.

In Delta, Utah today, most of the incarceration camp buildings are long gone. Plain yet bold signs mark where the hospital, housing blocks, churches, and yes, schools used to stand.

The Topaz Museum, a few miles down the road from the old site, is the result of a multi-year school project carried out in the late 1980s and early 1990s, courtesy of former Delta High School journalism teacher Jane Beckwith. It contains various artifacts from the camp and showcases artwork by detainees.

Beckwith’s newspaper students through the years also played a significant role in helping found and execute planning for the museum, which was built in 2013.

During this multi-year project, community interest spread. Soon enough, the project grew from a local history project in a journalism classroom to the Topaz Museum. Beckwith says the museum was “mostly the students’ idea.”

It’s fitting that high-school students brought awareness and eventually a museum to commemorate the Topaz site. Like the Ramblings, the museum is full of life, its artwork and artifacts bringing insight into a dark past.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook