Scottish Jews Have Their Own Official Tartan

It’s kosher!

From lochs to legendary castles, haggis to historical firsts, Scotland’s undeniable Gaelic charm is seducing tourists in record numbers. Visitors tend to be eager for all things Highlands, in particular a desire to purchase garments in that most definitive of Scottish patterns: tartan.

Each Scottish clan has its own tartan, a tradition popularized in the Jacobite era in which the novel and currently popular TV show Outlander takes place. Today, many communities compose their own unique tartans that represent a blending of heritages.

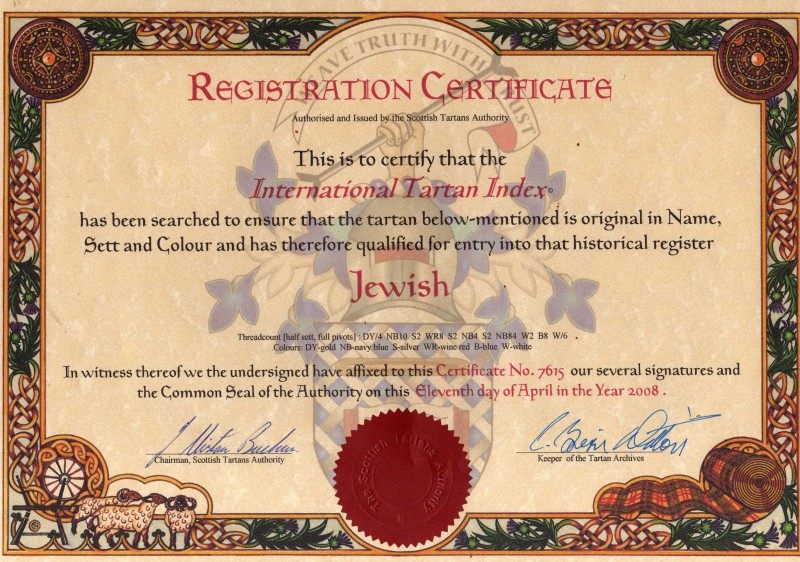

Scottish Jews, whose presence in the country was first recorded in the late 17th century, have designed two plaids, one deemed “official.” In 2008, Scottish editor Paul Harris and dentist Clive Schmulian teamed up to create the “Shalom Tartan,” but it wasn’t until later that they chose to register it with the Scottish Tartan Authority. By then, Mendel Jacobs—a Glaswegian Orthodox rabbi—had much the same idea. He’d long noted the increasing popularity of individual tartans for diverse communities of people, including religious and ethnic groups, and organizations like sporting clubs.

Harvey Kaplan, director of the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre, disputes the existence of a single “official” Jewish tartan. He estimates there are about 7,000 Jews in Scotland, lower than Jacobs’ estimate of 10,000. “Other than in Glasgow or Edinburgh, the Jewish population is spread thinly around the country,” says Kaplan. “It’s likely that most Scots never knowingly encounter Jews and many may never have met Jews.”

Jacobs chose to build and register a design, later dubbed the “Kosher Tartan,” with the Scottish Tartan Authority. He says, “This was an idea that people could both wear with pride of [being] Jewish and their Scottish heritage combined together.” Various aspects of this design harken to Jewish faith. It contains three vertical lines and seven horizontal ones; both numbers are sacred, three representing unity and seven, arguably the holiest number in Jewish numerology, symbolizing completion.

The central colors are blue and white, both of which decorate the Israeli and Scottish flags; they are complemented by lines of gold (representative of the Ark of the Covenant), red (Kiddush wine), and silver (the ornamentation on the scrolls of the Torah). In accordance with Jewish Law, Jacobs has ensured that all cloth products do not contain mixtures of wool and linen (a prohibited practice called shatnez). “It means a lot because [it’s] obviously part of my heritage,” says Jacobs. “It enhances a person’s ability to strengthen their own Jewish identity.”

According to writer J. David Simons in the Jewish Quarterly, “it is in Scotland’s cultural symbols rather than in its geographical presence that she [Jewishness] makes herself felt.” Jacobs’s Chabad runs a kosher restaurant, called L’Chaim’s, which provides faith-friendly fare for cultural celebrations. For example, they supply kosher haggis and whisky for Burns suppers, which are annual dinners conducted on January 25 celebrating the life of poet Robert Burns. For younger generations, there’s the Jewish Lads and Girls Brigade and Brownies and Guides* troops. Congregations sing Jewish prayers like “Adon Olam” to traditional Scottish melodies, while ceilidh dancing appears at synagogues and wedding ceremonies.

Jacobs sells Judaica bearing the tartan pattern in stores across the United Kingdom, and in the United States. His most popular products are small, portable accent pieces, like kippot, ties, scarves, shawls, flat caps, and sashes. But some also commission larger, customized items to measure, like skirts and kilts, for formal celebrations, such as bar and bat mitzvahs and weddings. “I have worn the kilt and the dress on occasion,” says Jacobs.

Interestingly, the people buying his products are more often tourists than native Jewish Scots. “It’s just something tourists want to do, expats want to do … have a piece of their heritage, a piece of that culture” back at home, Jacobs says. One of the “Kosher Tartan” kilts is now part of the collection at the Jewish Museum of New York, in whose gift shop visitors can also buy tartan goodies. Plaid can remind tourists of their trip and commemorate their rich heritage. “People buy tartan kippot, ties, kilts—but only a small minority, I would think,” says Kaplan. “It’s not a big thing here—more for the tourists!”

*Correction: The story originally referred to scout troops.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook