The ‘Black Mozart’ Was So Much More

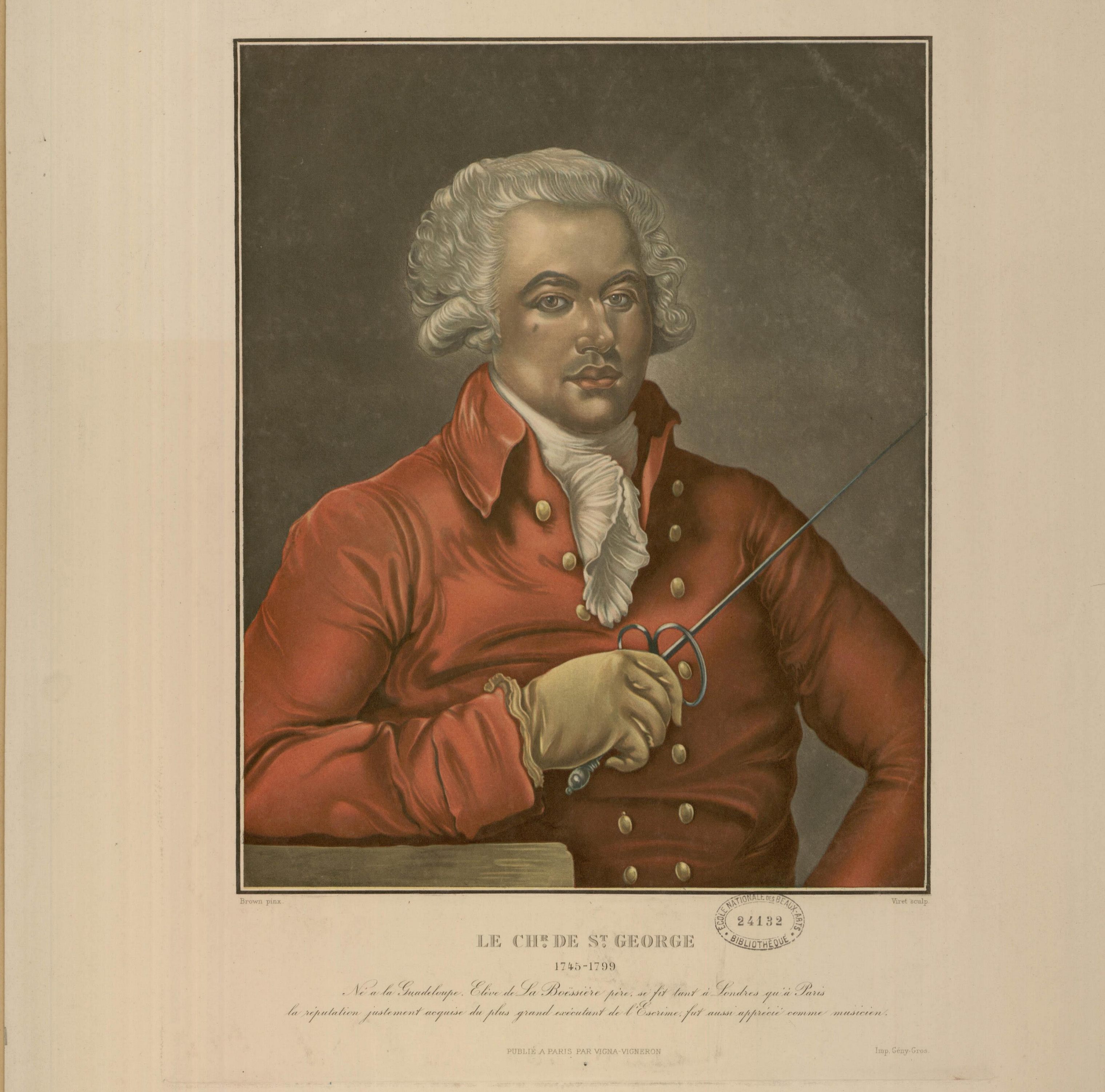

Between composing concertos, Joseph Bologne fenced and fought in the army.

The 40 years between the American Revolution and the defeat of Napoleon gifted the world some wonderful music. From Haydn’s string quartets, through Mozart’s symphonies, to Beethoven’s dazzling works for piano—a music lover could paddle around the period forever. But one great figure of the age is often ignored: Joseph Bologne, also known by his noble title the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. This is a pity. A person of Bologne’s talents—musical and military—is impressive whatever the era. That Bologne was black, and thrived in a racist society, is remarkable.

Bologne was born in Guadelupe, a French colony in the Caribbean, in 1745. His father was a wealthy plantation owner, his mother a black slave. As a mixed-race child, Bologne enjoyed considerable freedom and eventually went to study in France, where he quickly settled into the life of a rich enlightened Parisian. “Bologne had access to everything money could buy as a young man,” explains Chi-chi Nwanoku, founder of the Chineke! Orchestra, for ethnic minority musicians. It helped that his father was from an “aristocratic family,” adds Nwanoku.

But if Bologne’s youth was spent comfortably, bigotry was never far away. French racial laws meant he couldn’t inherit his father’s titles. Things got worse when he was 12, in 1762. New legislation forced black people living in Paris to register with the state. Still, some black citizens were able to scrabble up France’s social system. One freed slave had entered the Parisian middle classes, and opened a fencing hall. For his part, Bologne was an excellent fencer. “Due to his successes at fencing, he obtained much respect from his peers,” says Nwanoku.

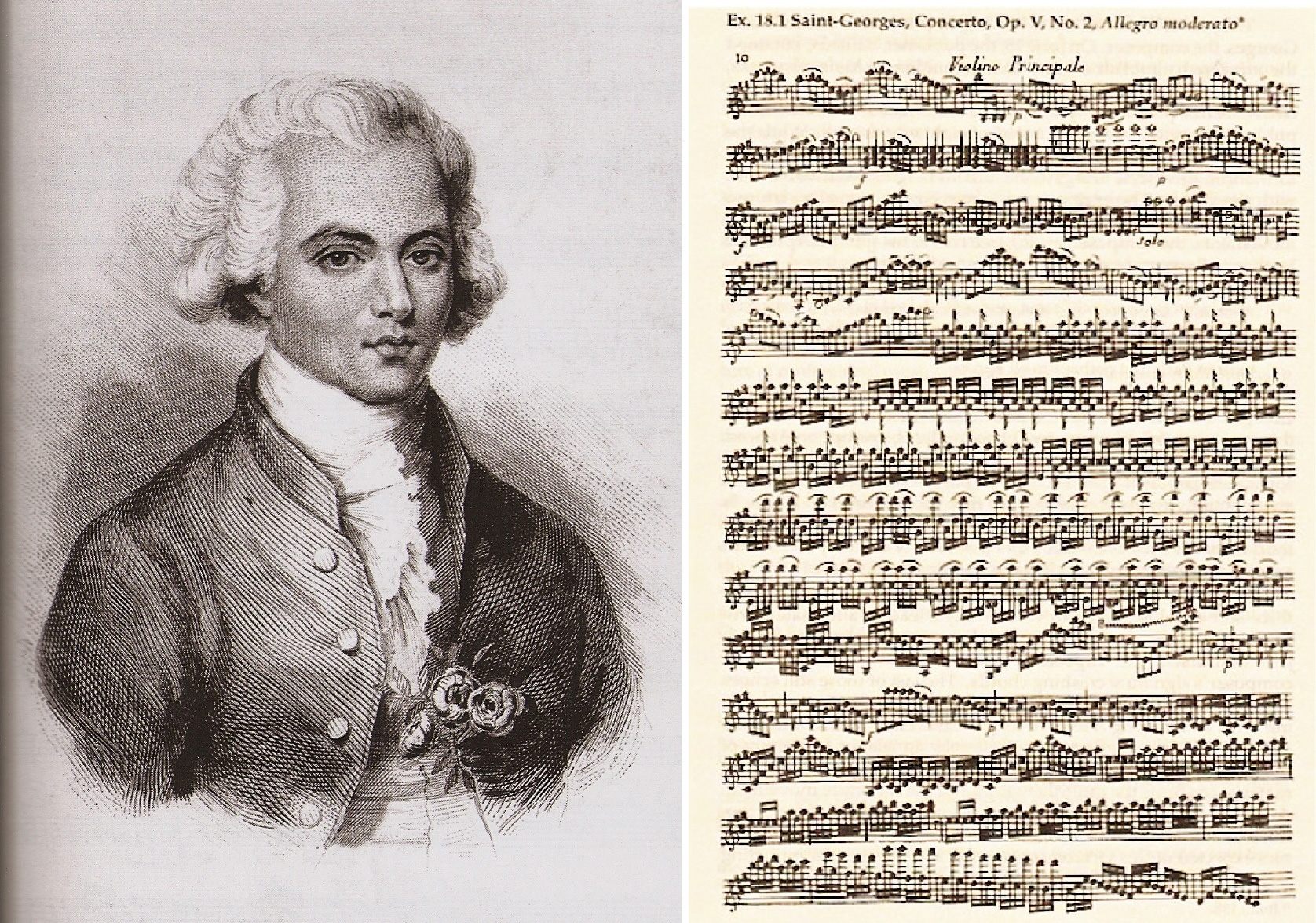

But if Bologne’s talents with a sword impressed contemporaries, it was his skill with a bow that astonished them. Bologne was a superb violinist. He also composed for the instrument. “It is no accident—and tells us a lot—that Mozart copied note-for-note from a Bologne violin concerto into one of his own [pieces],” says Nwanoku. “I believe Bologne’s violin concertos are technically more demanding than Mozart’s,” she continues. After all, some of Bologne’s pieces “extend to an octave higher.” Bologne’s operas and chamber pieces are also first-rate. For William Zick, founder of a website on black classical musicians, Bologne was “a full-fledged member of the world of classical composition in the 18th century.” This opinion was held at the time. One newspaper reported that Bologne’s work “received the greatest applause.”

Given all this, it is unsurprising that Bologne became known as the “Black Mozart.” He didn’t stop there. He led a prestigious Parisian orchestra, and often performed for Queen Marie-Antoinette. On a personal level, then, pre-revolutionary France could be strikingly tolerant towards race. But to quote one biography, society was always “ambivalent” about Bologne’s success. For instance, he was unable to take charge of the Paris Opera because colleagues refused to take orders from a “mulatto.” Elsewhere, Voltaire claimed that “mulattos … have refused this impulse of feeling and genius which alone produces new ideas.” Overall, says Zick, racism limited “the artistic value of [Bologne’s] music.”

These attitudes led Bologne into politics. Visiting London, he met abolitionists like William Wilberforce. He did similar work back in France. The revolutionary chaos that swamped France after 1789 also provided new opportunities. Despite his personal attachment to the queen, Bologne joined the revolutionary National Guard in 1789. The following year, he was made colonel of the “Legion of Saint George,” the first all-black regiment to ever fight in Europe. There was a lot to do: revolutionary France was at war with all its neighbors. Bologne fought well, protecting Lille from an Austrian attack. He also stopped the town from falling to the enemy after another officer defected.

In other words: Bologne not only pioneered black music in Europe, he also pioneered black political life. But as in the cultural sphere, prejudice limited his options. Following pressure from other soldiers, his all-black regiment was disbanded. Wider political changes hardly helped. As the revolution continued, it became more paranoid and authoritarian. By mid-1793, radical Jacobins led by Maximillian Robespierre had taken power in France. The mere suspicion of counter-revolutionary sympathies could mean death. Bologne himself was imprisoned for almost a year. Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, a slave rebellion in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti) had warped into a vicious race war. France abolished slavery in 1794, but the violence in Saint-Domingue made even white liberals nervous. Bologne’s anti-slavery stance was marginalized.

Indeed, when Bologne died in 1799, the newspapers carefully ignored his radical politics. They instead focused on his musical legacy. But even that was forgotten in the 19th century. Romantic composers like Beethoven and Schubert were more popular. Racism undoubtedly played a part too. As Claude Ribbe, a prominent historian of Bologne has written: “history texts have little to say about [Bologne], or of the million slaves deported to the French West Indies,” but “Voltaire is honored as the most brilliant humanist and Napoleon as the most glorious man of state.”

This attitude is changing, though. “In France today there are classical musicians and fans who regard the music of [Bologne] as comparable to that of Mozart,” explains William Zick. Several recordings of his music are now available, and he’s often played in concert. A 1997 documentary on his life has just been re-released for DVD. A street in Paris now even carries Bologne’s name. About time: Joseph Bologne deserves to be remembered, and not just as a “Black Mozart.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook