The Forgotten Kenyans Who Excavated Ancient Monuments

A new exhibition celebrates the African archaeologists and excavators omitted from historical records.

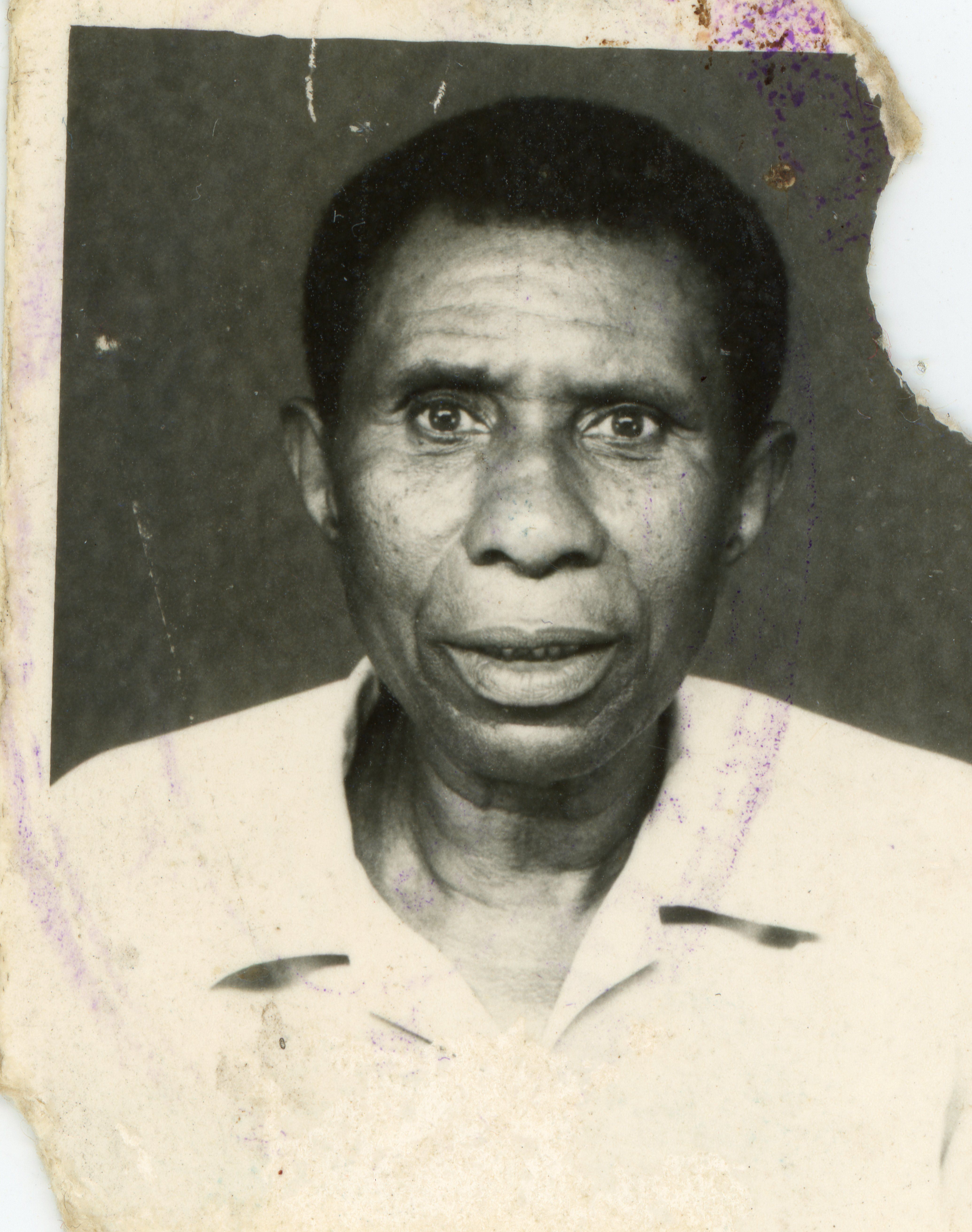

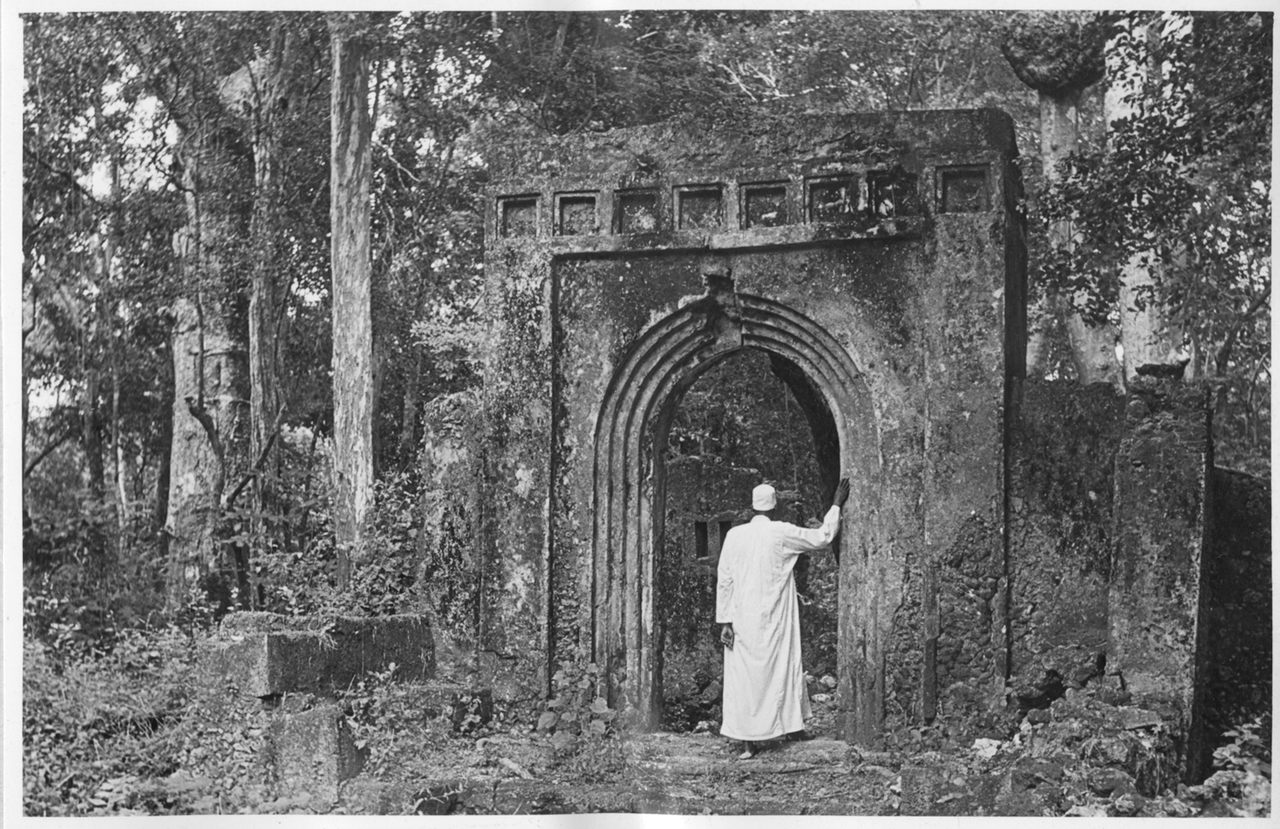

For more than 20 years through the 1950s and 1960s, Karisa Ndurya worked as a foreman at some of the first excavations of ancient monuments in East Africa. Under the management of Scottish archaeologist James Kirkman, Ndurya supervised teams of Kenyans who excavated the ruins of Gedi, one of the first medieval Swahili settlements on what is now the Kenyan coast, and Fort Jesus on Mombasa Island, the only fort maintained by the Portuguese. But if you were to read through Kirkman’s records on the excavations, you would not encounter Ndurya’s name or those of the Kenyans who labored alongside him.

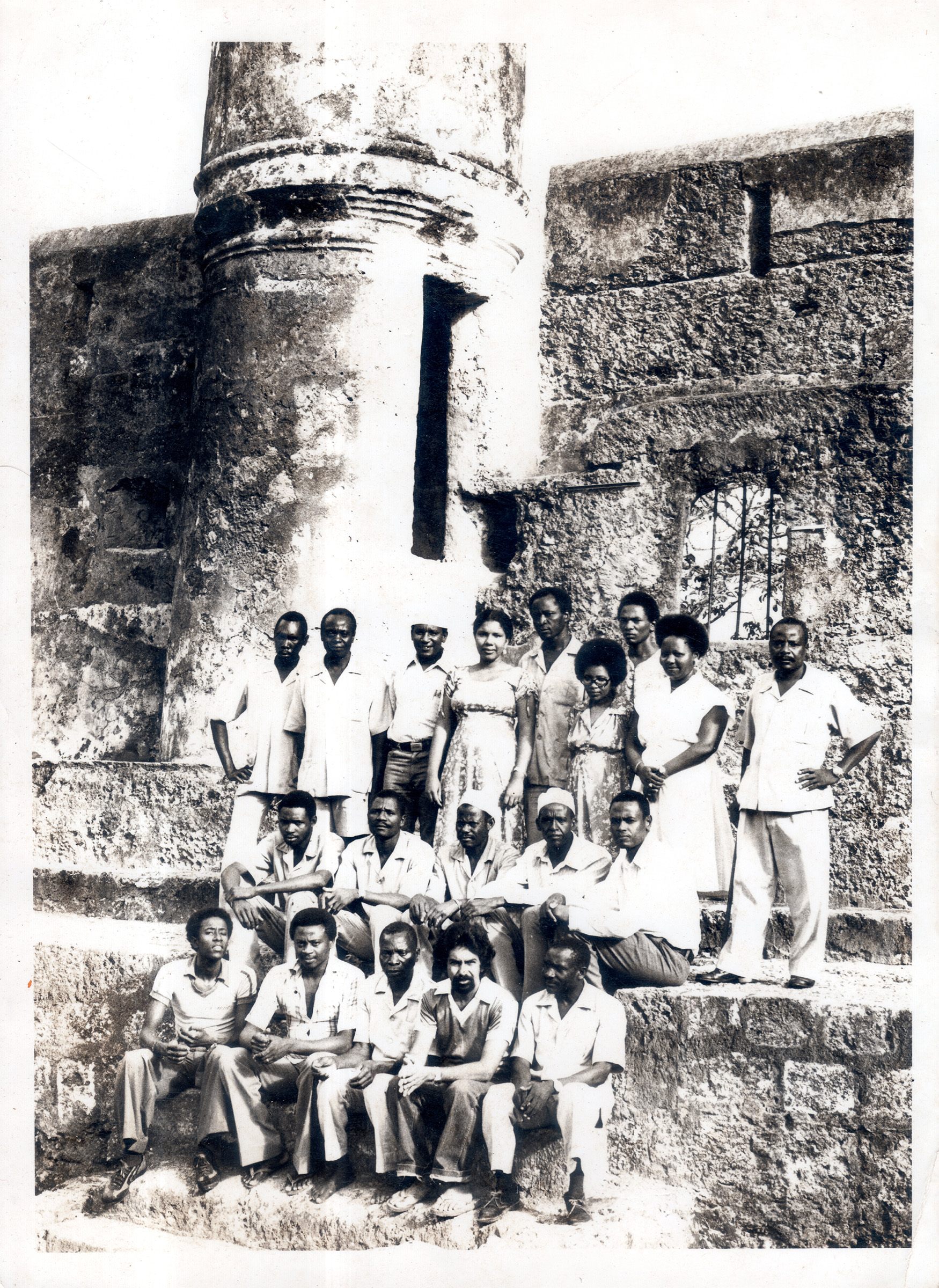

Fifty years later, a new exhibition aims to set those records straight. Currently on display at the Horniman Museum in London, “Ode to the Ancestors: Kenyan Archeology” is an exhibition of 28 previously unseen archival photographs commemorating the Kenyan archaeologists and excavators omitted from archaeological archives. The exhibit also features contemporary work by young people of African and/or Caribbean heritage, exploring what reclaiming African history means to them. A sister exhibition, where the same photographs are featured, is being held at the National Museums of Kenya at Fort Jesus. Both exhibitions were curated by Sherry Davis, a musician, filmmaker, and granddaughter of Ndurya.

Born and raised in South London to a Jamaican father and Kenyan mother, Davis never knew much about her grandfather, who died in 1988 at the age of 80. When her mother told her about Ndurya’s work as a foreman, Davis was surprised and went searching for more information. Despite learning lots about Kirkman, Ndurya’s boss, she couldn’t find anything about Ndurya. “I felt a strong sense of loss,” Davis says. “My family didn’t know much about his work because he died so long ago and didn’t leave any records.”

Before the 1970s, when African professionals began studying archaeology as a subject, almost all European archaeologists relied on the knowledge and labor of the locals, but their names and stories were rarely known. According to George Abungu, a Kenyan archaeologist and former director of the National Museums of Kenya, archaeology arrived in Africa at the same time as the colonialists. “The reason for colonialism was not only to dominate and subjugate, but also to extract knowledge, labor, and resources,” Abungu explains. “Archaeology was not an exemption, although I don’t think the archaeologists of that time saw themselves as extractors.”

In search of her grandfather’s story, Davis traveled to Gedi and to Fort Jesus in 2018 where she met with professional excavators who mostly worked in the 1980s and five heritage professionals who knew Ndurya but whose memories were too faded because “it was a very long time ago and they’re very old now,” she says. At Fort Jesus, during a tour with the National Museums of Kenya, Davis noticed that the walls of the fort were marked with Kirkman’s name and no one else’s. “I didn’t want my granddad to just be in the memories of people that weren’t going to be with us for much longer,” Davis says.

Davis found the same story at the Horniman Museum: its Kenyan archaeological collections had white Kenyan-British archaeologist and paleontologist Louis Leakey’s name attached to it. This was true at other museums in the United Kingdom, too. Frustrated with what she was discovering, Davis dedicated herself to searching for the names of those who had been left out of history and approached the Horniman Museum and the National Museums of Kenya about creating an exhibit telling a fuller story.

With the museums on board, Davis started working with Abungu and photo archivist Okoko Ashikoye to gather photos of the forgotten Kenyan archaeologists and excavators. The search for archival photographs, however, proved to be somewhat challenging. Ashikoye searched for photos at different institutes in Kenya, but the photographs were either not digitized or cataloged due to the lack of resources or they were taken in the 1970s and 1980s, after the colonial period. There were also instances where some photographs deteriorated or disappeared due to unfavorable archival conditions. Another problem was that not many photographs were taken of the locals at the sites in general. “You have hundreds of photographs of excavations of trenches that are empty,” Abungu explains. “But very few with the human beings doing the work.”

The deadline to print photos was looming, but a breakthrough came when, at the Fort Jesus archives, Ashikoye stumbled upon a box of roughly 500 images taken in the 1940s and 1950s of excavation expeditions at Fort Jesus and the ruins of Gedi. Three of those photos were of Davis’ grandfather overseeing excavations in 1959. As word of the development of the exhibition in Fort Jesus spread, people from the community started coming forward with their own stories. “One of the retired heritage professionals’ daughter came forward and gave information about her dad and it just had a snowball effect,” explains Davis.

“Ode to the Ancestors” shows the pivotal role Africans had in the pioneering stages of archaeology on the continent. According to Davis, the exhibition further emphasizes the importance of archaeology as a tool for Africans to tell their own stories. “Archaeology as a field is of the utmost importance,” she says. “And I hope projects like this that bring it to life in the context of telling African stories reignites more interest.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook