The Cosmic Fetus of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ Hasn’t Aged a Day

One of the most iconic props in film history is still circling the world.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the release of Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s iconic science-fiction movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey, as well as the birth of the iconic space baby that changed the face of the genre.

From the enigmatic monolith to HAL 9000 the rogue AI, 2001 introduced some of the most iconic concepts of the sci-fi genre. Maybe the most visually memorable was the Star Child, the uncanny infant that marked the cosmic evolution of the human race. Not only does the original Star Child prop survive today, it has continued to travel the world on a decade long baby’s day out.

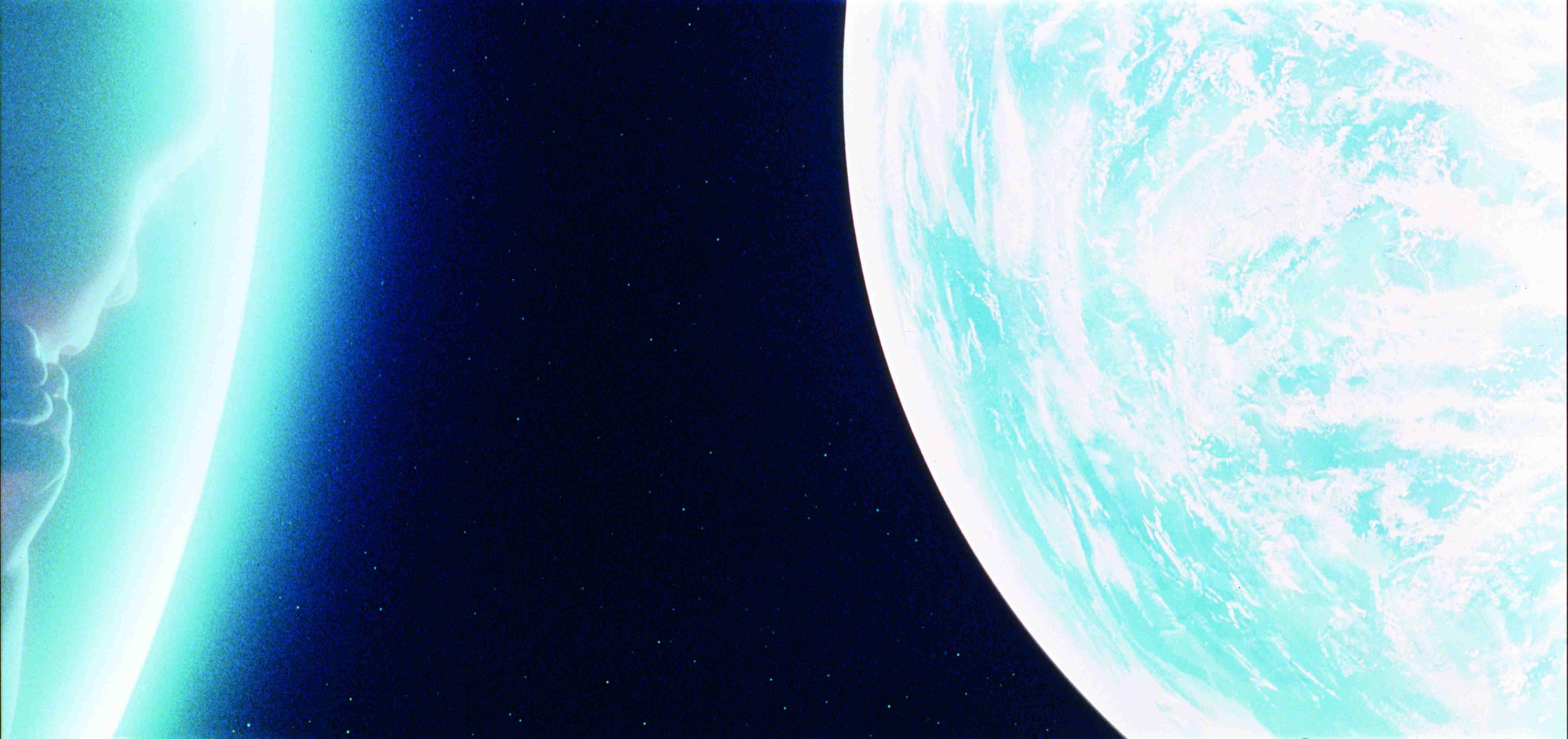

Released in 1968, (so, 50-year-old spoiler alert) the film chronicles the journey of astronaut Dave Bowman, the first human to travel through a stargate seemingly left behind by ancient aliens. After doing so, Bowman is transformed by a mysterious black monolith into a new form of life, a wide-eyed fetus held in a glowing orb. The meaning and exact details of this event are widely debated, but the Bowman/Star Child represents the birth of the human race into a new future as a universal species. Fight me.

The Star Child only appears for a brief instance at the very end, yet it has still become one of the most important icons in the history of film. And while in the movie it is left overlooking Earth from the stars, the real-life prop is on display in a traveling exhibition of Kubrick artifacts.

“The Star Child was built in autumn 1967 in the 2001 art department at the British MGM Studios,” says Tim Heptner, curator of the traveling Stanley Kubrick Exhibition, which features the original Star Child prop as one of the main attractions. “I started to look after the prop when it became part of the Stanley Kubrick exhibition in 2004 … so I have been traveling with this prop for quite a while.”

Sculptor Liz Moore created the Star Child after test shots of a living baby lying on a black velvet backdrop didn’t work out to Kubrick’s liking. According to a history of Moore, and the prop’s creation, on the fan blog 2001 Italia, Kubrick wanted the transformed Bowman to look more cosmic than an actual baby, and was inspired by then-ground-breaking in-utero photography. “Inspiration for the fetus-like (and a bit eerie) star baby sculpture which is traveling in space in an uterus-like bubble came from an illustration in Robert Ardrey’s book, African Genesis, and through the intra-uterine photographs by Lennart Nilsson which were published in 1965 in LIFE Magazine,” says Heptner.

Moore sculpted the two-and-a-half foot tall baby creature out of clay, incorporating the facial features of actor Keir Dullea, who played Bowman in the film. Then a final version was made from fiberglass and outfitted with mechanisms to make the eyes movable. The baby’s crown detached, allowing the insides of the bulbous head to be accessible.

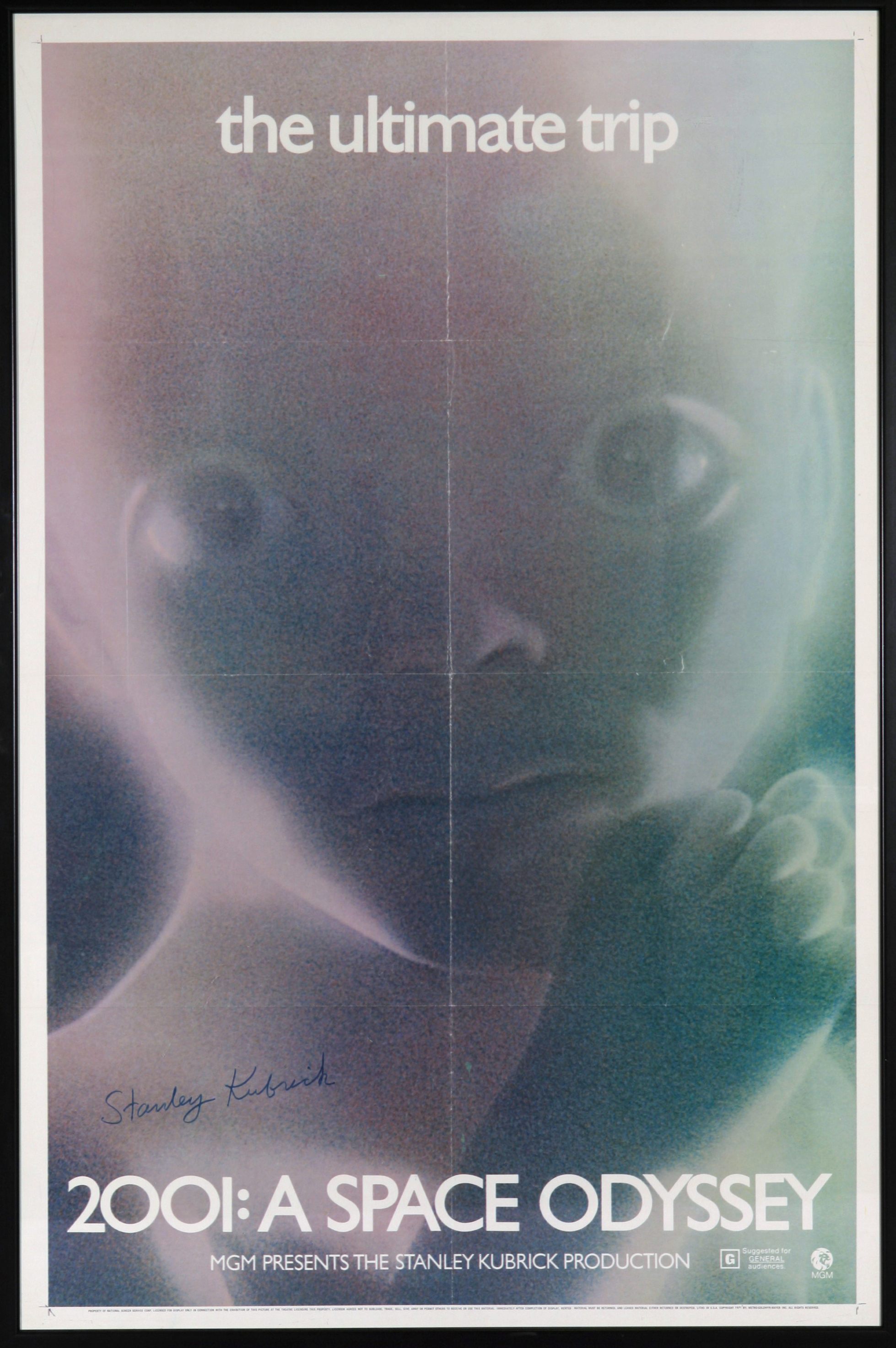

In addition to appearing in the film, the fiberglass fetus was used in promotional materials, including the “Ultimate Trip” poster shown below. Most shots of the Star Child have an ethereal, heavenly glow, and a placental halo, which Kubrick created using a handful of tricks including shooting the prop through a layer of pre-WWII women’s stockings. But at their heart was the same fiberglass baby.

After the film’s release, the Star Child prop dropped out of view, tucked away in Kubrick’s personal collection. “We don’t know what happened exactly with the prop between 1968 and 2003, but in [2003] the archivist of Deutsches Filmmuseum, my colleague Bernd Eichhorn, found it when he was sifting through the estate of the film director at his country manor in England,” says Heptner. Luckily, despite decades of earthly disregard, the prop was largely undamaged, with just a few tape marks to be removed. It remained as oddly serene as it had been in the 1960s. Not long after that, the Star Child was added to the traveling exhibition, where it is still cared for today.

Unlike a real baby, the Star Child doesn’t require a whole lot of maintenance. It’s dusted and cleaned like any other exhibited object and has been lucky enough to avoid any major damage over the years. When it’s moved it’s safely placed in a padded box that itself could be part of the exhibition’s display. “We store and transport it in a vintage trunk which the Kubrick family has used before, on their Atlantic passage, when they were relocating from the U.S.A. to England in the mid 1960s,” says Heptner.

Currently the Stanley Kubrick Exhibition is on display at the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt, and will continue to travel the globe, showing off the Star Child for the foreseeable future. With CGI increasingly replacing props and practical effects, such artifacts are becoming increasingly rare. “It is a striking and unique object, a strong and attractive ‘character’ in the narrative of the exhibition,” says Heptner. It’s a piece of cultural history that, like the evolved form of the astronaut Bowman, symbolizes a vision of the future.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook