Toward a Better Understanding of South Asia’s ‘Living Bridges’

Human and plant, working together.

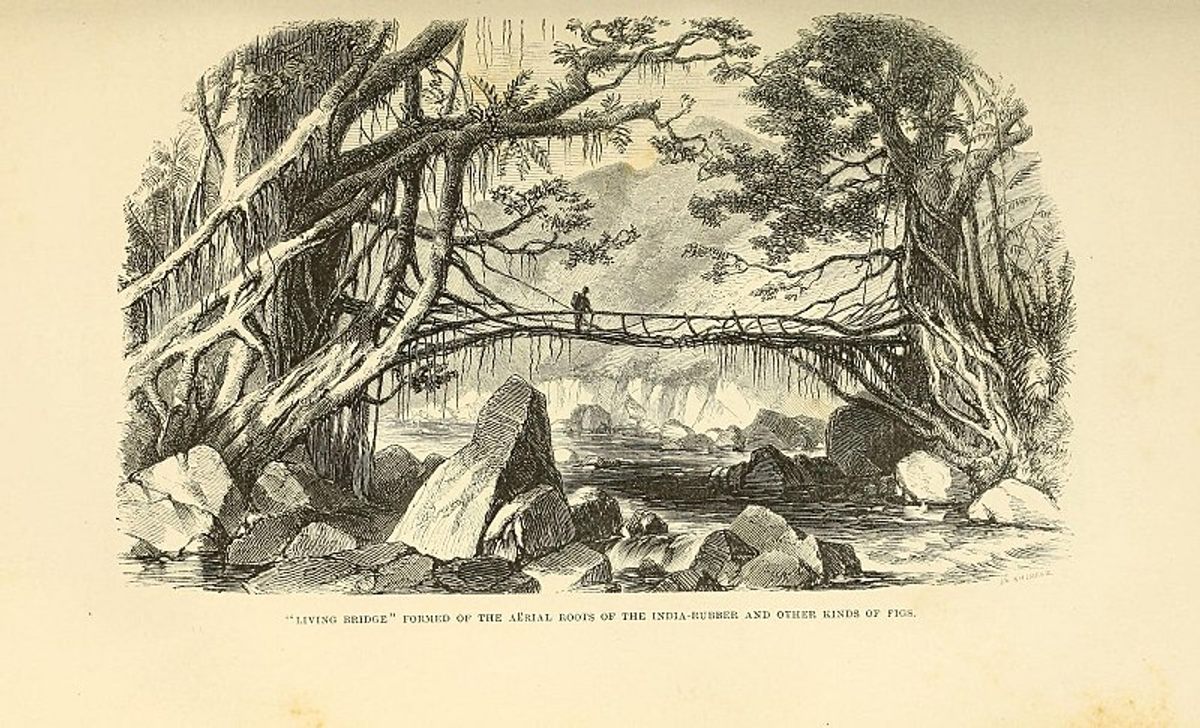

On the border of India and Bangladesh, bridges can build themselves. Under the dripping green overgrowth, root systems—guided by human hands, historically the indigenous Khasi and Jaintia people—twist and tether together gradually, forming structurally sound “living bridges” across ravines and rivers. Earlier this year, a team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) analyzed the famous, remote bridges to see how they take shape over centuries.

India’s Meghalaya State is one of the wettest places on Earth, with nearly 500 inches of rainfall in the average year. Bridges are more than helpful, they’re downright critical in monsoon season, when the rain can turn meandering rivulets into torrents in the region’s varying topography. That topography makes traditional construction challenging, as well, so living bridges have grown to fill a critical need. And the people who make and maintain them know the ins and outs of the process.

“Construction techniques make use of the specific adaptations of growth of aerial roots of Ficus elastica,” says Wilfrid Middleton, an architect at TUM. “This is important—all living architecture techniques must reflect the trees from which they are grown.”

F. elastica is, as its name suggests, is a rubber tree native to Southeast Asia. The new research, published in the journal Nature, examined and mapped 74 different living bridges in the area, all made from the roots of the rubber tree. The tree’s aerial roots—spindly, vine-like feelers that latch on to anything nearby for support—are directed by people over rivers by bamboo or palm stems, which form a sort of scaffolding for the plant to follow. Once a guided root grows across to the opposite bank, the root walkway and railings begin to thicken. This is not an overnight process; nurturing seedlings into towering trees and guiding their growth can take generations.

An additional useful feature of the rubber tree, Middleton says, is how their roots graft together, so that multiple trees, on opposite sides of a chasm, can grow to become one sturdy construct. “Combining these,” he says, “construction techniques are developed, like tying a network of knots that create a stable deck and handrails.” The most robust bridge structures can hold dozens of people at once.

But the bridges don’t stay so sturdy on their own. Locals maintain and guide them daily, Middleton says, by either tying the roots into the existing structure or pruning them back where necessary.

The result is a remarkable display of teamwork between the plant and animal kingdoms. Not only do humans benefit, but the plants on either side inosculate—a fancy term for two a merger of root systems that allows plants to share water and nutrients.

“From a structural perspective, the inosculations provide two functions,” Middleton says. “A network of roots distributes forces between roots across the whole structures, possibly preventing damage. The complex network also provides redundancy—if any root is damaged, many other roots can take up their slack as load paths or water transport routes.”

The living bridges of Meghalaya are difficult to get to, but it’s worth the trip to see a wonder that is both man-made and natural at the same time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook