How a Thirst for Portuguese Wine Fueled the American Revolution

Madeira taxes stoked tensions, then paid for the war.

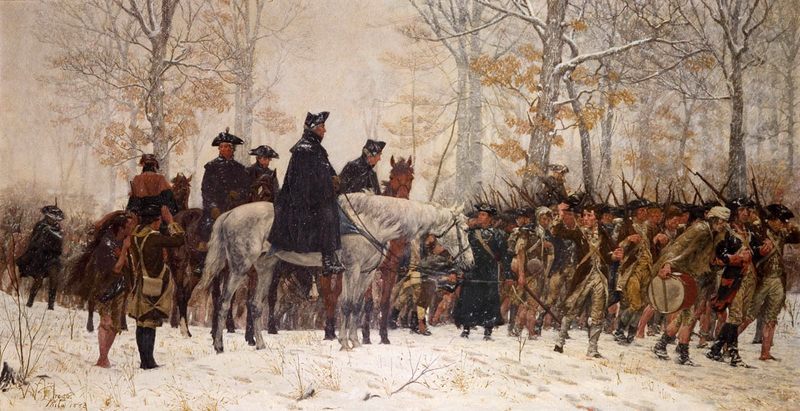

In the summer of 1775, as General George Washington outfitted his first mobile headquarters for the newly formed Continental Army, he seems to have intuited the importance of creature comforts. His personal expense accounts in 1775 and 1776 detail countless purchases that would allow a privileged man like himself to remain comfortable as he superintended an increasingly anxious volunteer army: trunks, table linen, curtains, bedding, and, perhaps most important of all, copious amounts of wine.

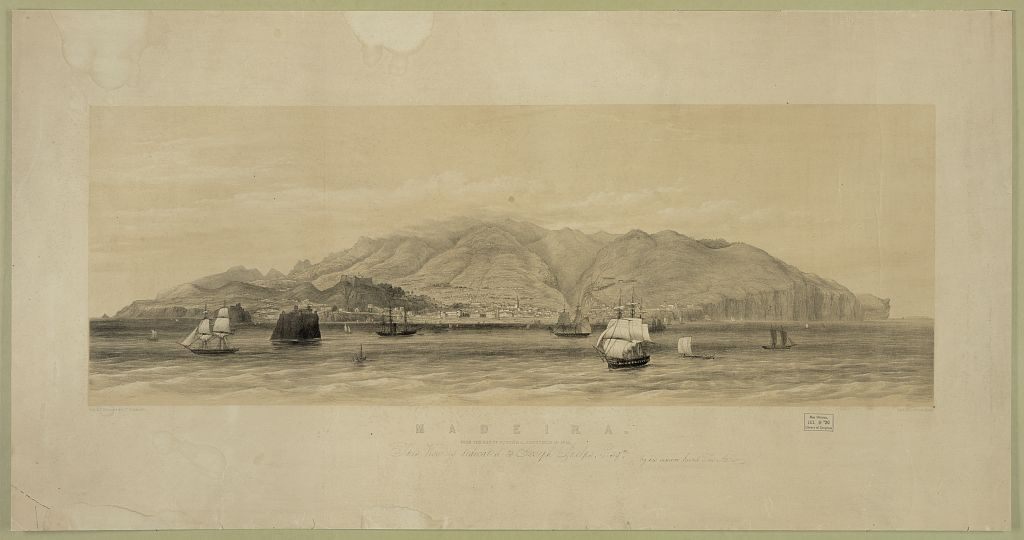

Life in an 18th-century war camp vacillated between extreme emotional duress and mind-numbing boredom. To help cope with this volatile existence, he and his officers required booze. To this end, Washington ordered a dizzying volume of what had long ago become colonial-America’s favorite adult beverage: madeira, a fortified wine produced on a small Portuguese island located 360 miles west of Morocco.

On August 8, 1775, two months after taking charge of his army, Washington procured a large cask of the wine, as well as empty bottles, corks, and other paraphernalia. Over the next six months, he purchased hundreds of additional bottles and, eventually, an entire “pipe” (a term derived from the Portuguese word for barrel, “pipa”). A pipe of madeira held enough wine to fill 700 bottles, and a cask roughly the same. Washington, then, in preparation for war, ordered at least 1,900 bottles worth of the wine to be shared among his closest aides and confidants.

That he chose madeira is not surprising. Colonists had indulged in Madeiran wine since the 1640s, and, by the mid-18th century, British North America accounted for a quarter of the island’s exports. For nearly a century, exclusivity and happenstance were the prime agents in this popularity. Because colonists preferred the taste of madeira that had aged and cooked in the belly of merchant ships, it was one of the few wines to benefit from the length and unpredictability of transatlantic travel. By Washington’s era, however, America’s thirst for madeira transcended convenience. According to David Hancock, a historian at the University of Michigan and author of Oceans of Wine: Madeira and the Emergence of American Trade and Taste, Americans favored the wine because its makers pioneered production techniques in direct response to consumer feedback.

“Through correspondence and contact, they learned there were many palates in the English-speaking world,” he says. “So, they altered the formula to suit different tastes, negotiating them with American and British distributors and consumers in response to the preferences of drinkers in particular regions.”

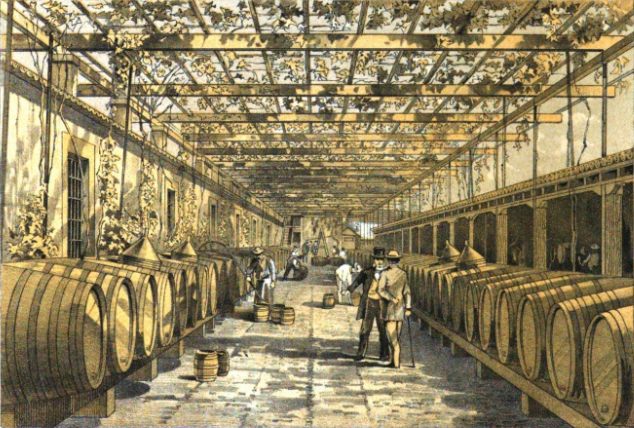

South Carolinians and Virginians, for instance, preferred heavily fortified wines, which were dry and “white as water.” Philadelphians liked sweet golden varieties, and New Yorkers favored sugary red sorts, which were comparably low in alcohol content. To meet these unique demands, Madeirans blended varietals and wines from different vineyards, adding coloring or sweetening agents for northern colonies, while reducing color and tartness for Southerners. Most importantly, in the second quarter of the 18th century, they began to fortify madeira with brandy.

“This became the principal means of alteration,” Hancock says. “Without treatment, new wine bore a reddish and sweetish taste. Adding brandy directly altered both traits, and these were traits on which consumers weighed in constantly.”

Throughout the American Revolution, these custom formulas proved immensely popular in British North America, making the wine ubiquitous through many of its hallmark events. In 1766, John Hancock celebrated the repeal of the Stamp Act by setting two pipes of madeira out in front of his house for public consumption. Two years later, he protested newly established import taxes by intentionally underreporting the number of pipes he’d imported. In response, custom officials seized Hancock’s ship, which soon encouraged a mob to gather around the port of Boston. The group, reportedly 3,000 strong, eventually destroyed a ship owned by Joseph Harrison, the port’s chief customs collector. Months later, British officials used the incident to justify an increased troop presence in the city—a decision that ultimately led to the Boston Massacre.

Hancock, of course, was not the only Revolutionary icon to conspicuously consume madeira. In 1774, John Adams reported to his wife, Abigail, that after tedious days of contentious debate, delegates to the First Continental Congress would sit for hours “drinking Madeira, Claret, and Burgundy.” One year later, Thomas Jefferson famously toasted the signing of the Declaration of Independence with madeira. And then there was Washington. As the war progressed, he used his long-standing relationships with madeira importers to maintain a steady stream into his headquarters, even after Portugal, an ally to Great Britain, closed its ports to American merchant vessels.

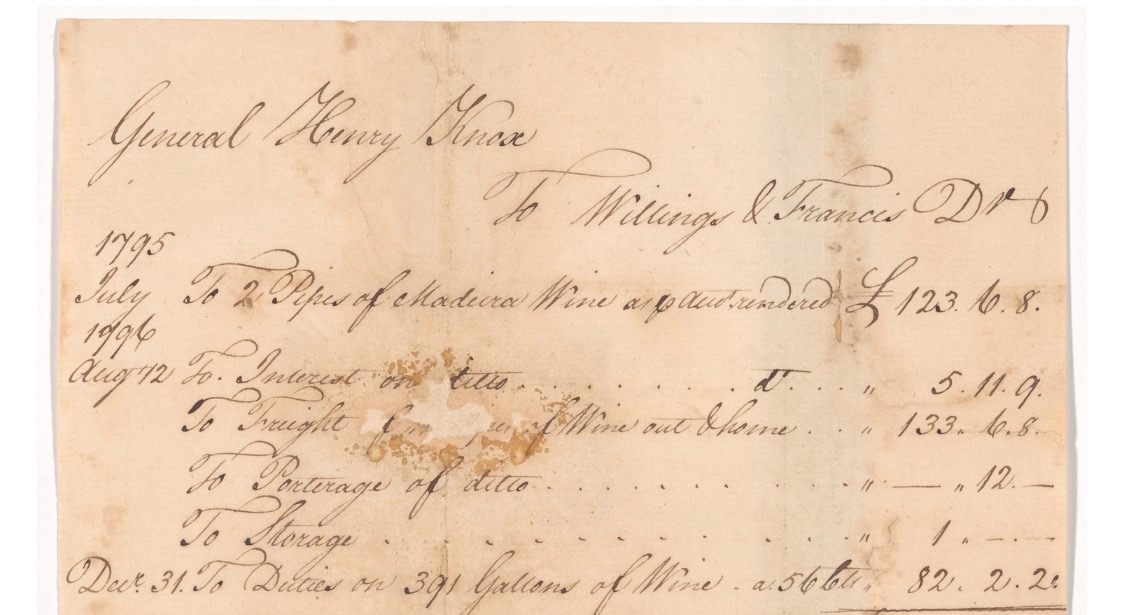

When the war ended in 1783, America’s relationship with madeira flipped on its head. The same men who had rioted over import taxes now found their revolutionary fervor tempered by pragmatism. During the conflict, the colonies accrued substantial debt. Throughout the 1780s, the nascent states weighed several options. Averse to property and poll taxes, and intent upon leaving domestic trade unburdened, several state governments began to levy tariffs on foreign goods—particularly wine and spirits. By 1790, the federal government had also adopted this process, which taxed British and Portuguese exports at much higher rates than those produced by allied nations. This assured that rum and madeira sales accounted for a disproportionate share of state and national revenue.

Unfortunately for Madeiran merchants, these taxes, combined with an increasingly competitive transatlantic market, eventually eroded their hold on America. Before the war, Spanish and French wines had suffered under suffocating regulations. But afterward, they became increasingly competitive in North America. Between 1787 and 1790, exports from these nations to the U.S. grew exponentially. By 1807, sherry and St. Lucar wines eclipsed madeira in popularity, and the Portuguese soon turned their attention toward India and other newly opened markets within the rapidly expanding British Empire.

Though Americans, particularly Southerners, continued to drink madeira into the 19th century, the drink eventually transitioned into a niche dessert wine. Still, by then, it had already secured its legacy, having attached itself not only to late-colonial lore, but also to the early history of intercolonial commerce.

“Madeira wine was extremely important to the economy of North and Caribbean America, and to a significant portion of the Atlantic market,” Hancock says. “It and a handful of other early-modern commodities like cod, ceramics, and hardware flowed to communities around the ocean and the world with little respect of borders, knitting together oceanic and global communities, and establishing a model for transnational, inter-imperial exchange where little like it had existed before.”

As for Washington, old habits died hard. Records exist from the third and fourth years of his presidency (1793 and 1794), which detail orders for six pipes of madeira intended for his house in Philadelphia. He enjoyed the beverage literally until he lay on his deathbed. On December 13, 1799, the day before he succumbed to a throat infection, someone in his household wrote an urgent letter to a Madeiran wine importer. “I lately received a letter from J.M Pintard, Esqr. in which he mentioned that he had some Madeira Wine of a very superior quality,” it read. “If you should think proper to send the General one pipe of the wine mentioned … your draft for the amount, at ninety days sight, will be duly honored.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook