Mapping the Hidden Structures of New York City’s Internet Networks

The internet is woven everywhere in city design; you just have to look closely.

A construction worker sprays a cryptic telecommunication marking. [Photo: Z22/CC-BY-SA-4.0]

Some of the most underappreciated, complicated architecture lies hidden beneath the city’s surface. Buried below asphalt and concrete is an intricate labyrinth of lanes carrying beams of information—the flowing data of the internet. Our emails, cat gifs, work files, Facebook messages, and most private secrets are funneled through miles of copper, coaxial, and fiber optic cable built just beneath our feet.

While hidden, a lot can be discovered about a city’s underground network from spray painted cryptic codes and special language left behind from construction.

“When I first got interested in finding the spray paint markings, I kind of couldn’t stop seeing them,” says 29-year-old, Brooklyn artist and writer Ingrid Burrington. “I have folders and folders of photographs on my computer of just spray paint on the ground.”

Burrington diligently deciphers the tiny marks scattered around city streets, discovering what kind of cables serve which buildings and what company oversees them. For the better part of the past three years, she wandered the streets of Manhattan identifying paint on asphalt, designs of manhole covers, historical data centers, cell phone towers, and inconspicuous WiFi nodes in subway stations. In her new book Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure released August 30, Burrington maps the complex world of telecommunications in New York City, revealing hidden pieces of the internet embedded throughout the city’s fabric.

Can you spot the faded telecommunications markings on this street? [Photo: Public Domain]

Burrington became interested in the strange way we interpret and represent the internet in 2013, when the news was filled with stories about Edward Snowden and network security. Stock images of strings of code on a laptop or blue-tinted stills of white men looking at screens are commonly attached to news articles about the internet or technology. The abstract visualizations feed into a misrepresentation, making networks appear as a nebulous, magical entity. “It can scare and alienate people, that sort of black screen, matrix syn-art,” Burrington says.

With this mindset, she decided to use elements of cartography in order to clearly define real aspects of the internet. “Maps are really interesting historical instruments for inventing reality and for deciding the makeup of a state or a place,” she says. “I think with telecommunications and the dominant technology companies, I like to map out and understand the power dynamics in those spaces and how they got to be that way.”

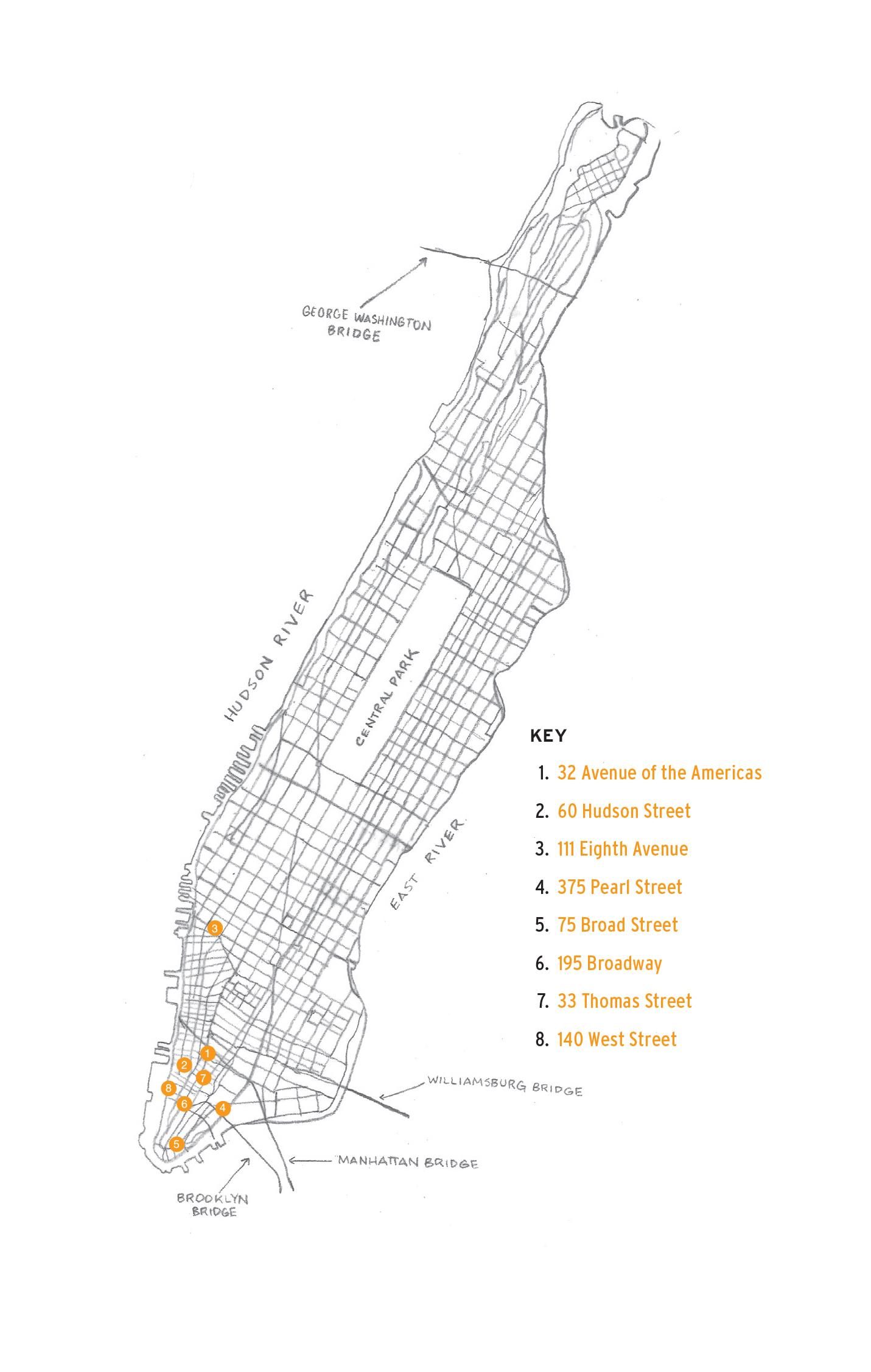

This map illustrated by Burrington shows locations of major carrier hotels and data center buildings in Downtown and Lower Manhattan. [Photo: © 2016 Ingrid Burrington]

New York City, which is over 300 years old, has a rich and messy telecommunications history. In most cities, technology and telecommunication networks must follow the groundwork that has already been established in the design plan. The glass tubules of fiber optic cables follow the coaxial cable television lines, which follow the copper telephone and telegraph lines laid down in the 1880s, which followed the railroad tracks. Now, the 2012 LinkNYC challenge to install 7,500 free Wi-Fi kiosks throughout the five boroughs are replacing old payphone booths. This will require some new fiber lines, but it’s mostly patchwork, Burrington explains.

“[The network] gets built up in this strata,” she says. “You use what’s already built out.”

In South Bend, Indiana, for example, a developer is trying to build a large data center hub in an old central train station because of the fiber that runs adjacent to the railways. In fact, a lot of data centers and “legacy fiber” runs along the Iowa and Nebraska border, which is the location of the initial transcontinental railroad tracks.

New York Stock Exchange in the Financial District. [Photo: MarshalN20/CC BY-SA 3.0]

If you want to see a lot of neon arrows, lines and network markings, Burrington suggests you visit the Financial District in lower Manhattan. There are countless construction zones taped off between the tall gleaming buildings, completely riddled with the orange spray—a national standard color code for communications, alarm, signal lines, cables, and conduit. The area is known for its abundance of telecommunications buildings and structures because the stock market on Wall Street demands super speedy internet service (less lag equals faster trades).

Burrington stared at the ground and noted signs such as the “f” and “o” bisected by a two-tipped arrow that signifies ‘fiber optic’ cables and the diamond pattern that denotes duct width, which she writes looks a lot like TIE fighters in Star Wars. However, she found that the signs would differ significantly from site to site.

“Depending on the particular stylistic decisions being made by the utility locator, they’re going to vary a lot,” she says. Since they didn’t look uniform, she opted out of using her photographs and instead draw each of the symbols and all the illustrations throughout her book by hand. The guide is meant to be used around the city, so she “didn’t want people to be looking for a photograph image,” she says.

An illustration of the Time Warner Cable manhole cover. The logo is supposed to be an eye merging with an ear. [Photo: © 2016 Ingrid Burrington]

Manholes—entry points to the city’s underground cables, power grid, and gas system—also get worn down from traffic. New York’s manhole covers are emblazoned with the insignia of the company that owns the lines underground. However, there are some mystery manhole covers. Burrington found that many companies do not replace covers of the new manholes they acquire, the cost being a lot higher than having recognition. Some manhole covers don’t reflect the company that owns the line. During the dot-com era, there was a boon of companies that merged and broke off and then re-merged, resulting in a twisted mess of cables. Now, there are more generic designs that indicate a water or communication line.

An illustration of a generic communication manhole cover. [Photo: © 2016 Ingrid Burrington]

The information Burrington collected has already proven valuable in addressing inequities in internet access in New York City. A previous, self-published edition of Networks of New York was used in a lawsuit regarding lack of internet access and digital divides in the Bronx. The attorney presented the book to try and obtain maps of cable ducts in the area.

“[The company] refused to give it to her on the grounds of national security and business secrets, but one piece of evidence introduced was this book,” Burrington says, the attorney arguing that someone had already made a “tour guide” for finding the cables. “It’s nice when the book encourages a broader interest or expands into issues that are related to access and equity.”

Burrington hopes others will be inspired to create other guides or crowdsourced maps of network infrastructure. [Photo: Jonathan Minard]

For those who do not live in New York City, you can still use Burrington’s guide. The spray paint markings are nationally used, and the manhole patterns are commonly found across the United States. Currently, a man in Phoenix, Arizona is working on a guide, and Burrington assisted a colleague in making a miniature infrastructure guide to London. Burrington hopes that the book inspires people to not only make network guides for other cities, but to pay attention to discreet facets of urban design that allows a city to function.

“One of the things that you’re not supposed to do as a New Yorker is look down and look up,” Burrington says. “But doing that has made me a lot more cognizant of the volume of stuff and history and labor that goes into it being possible for me to check my email while standing on a street corner.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook