Cool, There’s Water on Mars. But Does It Make Good Pickles?

What would happen if briny Martian liquid met an Earthling cucumber?

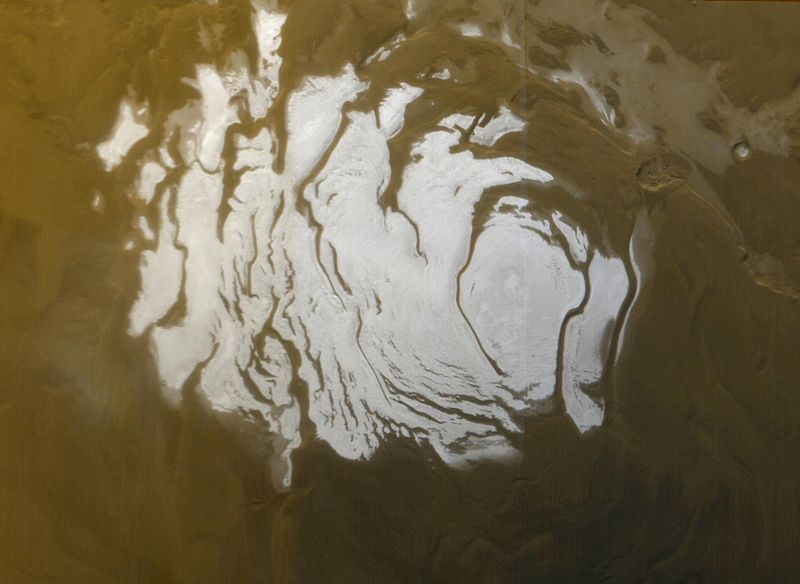

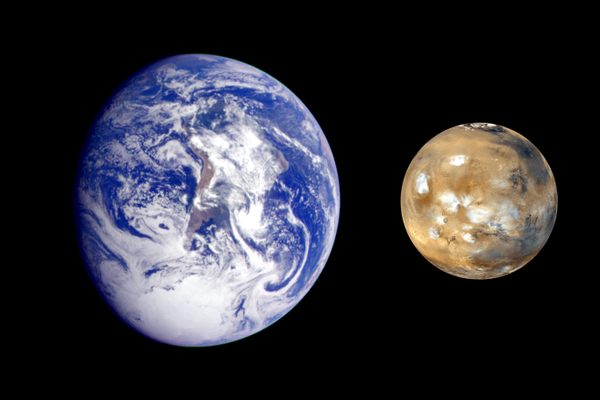

Deep under the ice cap of Mars’s southern pole, there could be a store of water, the first stable body of liquid water ever found on the planet. After the paper announcing this discovery came out, reporters described a “lake of liquid water,” about 12 miles in diameter. Hearing that phrase, it’s easy, perhaps even natural, to imagine a bubble of crystal-clear water, hidden under the cap of frozen water and carbon dioxide, pure and sweet and waiting.

But the reality would be less appealing. The pressure of a mile-thick layer of ice changes the conditions under which water can be liquid, by decreasing its freezing point. Even so, to stay liquid at around -90°F, the “lake” would have to be a briny layer of water, rather than a pool of pure (or even drinkable) water.

Briny water has its uses, though. For instance, what if Martian water was used to make pickles?

On Earth, going back centuries, brines made with salt (the NaCl kind) and other chemical compounds, such as calcium chloride, have been used to preserve food. Sugar is an energy source for microbes, and if the wrong ones start feasting on a vegetable, it becomes unfit for human consumption. But salt can cultivate an environment that only certain desirable bacteria can survive. The salt also helps leach sugars from the cells of the vegetable, and the bacteria consume the sugar and excrete lactic acid. Many microbes also have a problem tolerating acidity, so the acid also keeps at bay microbes that are undesirable (for the purposes of human consumption, at least).

Ultimately, pickling is meant to deal with the microbes that were already living in and on the vegetables and that, given a chance, would create rot or mold or otherwise make the vegetable inedible. “The purpose is to eliminate the indigenous microbiota, essentially,” says Ilenys Perez-Diaz, an associate professor of food science at NC State University.

Too much salt, though, can stop advantageous bacteria from working. It can still keep the food from rotting away—ham, for instance, is preserved simply by adding a ton of salt—by stopping all microbial growth. If the goal is preservation through fermentation, though, too much salt can slow the process down to a crawl. Also, there’s a limit to how much salt a person can take, and an overly salty brine can make pickles inedible.

The Mars water would definitely be too salty to survive for the lactic acid bacteria that are key to Earthling pickling processes. Measured in “practical salinity units,” ocean water has a salinity of around 35 PSU; the Dead Sea has a salinity of around 40 PSU. Pickling brine falls somewhere in between. But there are lakes in Antarctica where the salinity hits 200 PSU or more, and it’s possible that the Mars water could have similarly high salinity.

So, if you were to immerse a cucumber in Mars water, it probably wouldn’t rot away. But it wouldn’t be transformed by those hard-working lactic-acid producing bacteria into a delicious, sour treat.

What about other bacteria, though? One of the exciting things about liquid water on Mars is that it could be a habitat for microbes—the first alien lifeforms we’re likely to encounter. If those microbes stumbled upon a cucumber, would they be at all interested in it as a potential source of food?

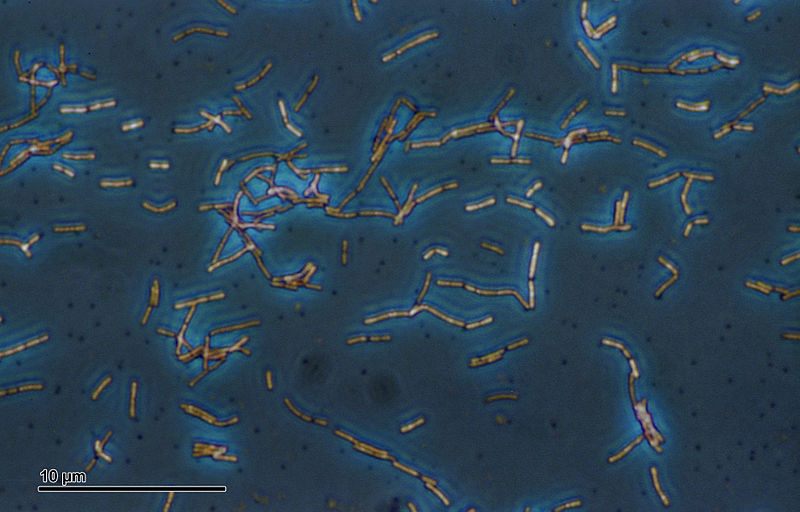

We obviously don’t know much about microbes on Mars, because we’ve yet to discover them (assuming they exist at all). One of the closest analogues on Earth, though, are extremophile microbes that live in subglacial lakes, not unlike the Mars lake.

While most microbes we know about on Earth, like most life on Earth, get their energy from a food chain that starts with the sun and photosynthesis, microbes in subglacial Antarctic lakes don’t have access to the sun. Instead, they use inorganic compounds as their source of energy. As the ice sitting over these lakes moves (albeit slowly), it puts pressure on the bedrock below, grinding the rock down and releasing compounds such as iron and sulfides into the water. The lake-dwelling microbes can oxidize those minerals the way other living things fix carbon, creating energy and keeping themselves alive.

Ultimately, though, we know very little about these microbes. “We’ve sampled one of these lakes in Antarctica,” says Brent Christner, a microbiologist at the University of Florida, who studies subglacial lakes. “There are 400.” The microbes they’ve found so far resemble microbes that live in other, somewhat more accessible places where sunlight and organic materials are impossible to come by. Christner and his colleagues are planning on sampling another subglacial Antarctic lake soon, and the microbes living in that next lake could look similar—or be totally different. We just don’t know.

Given this limited information, though, it’s safe to say that the glucose and fructose of a cucumber would be totally foreign as a potential food stuff for subglacial lake microbes. Cucumbers do contain small amounts of iron, but even that likely wouldn’t be of much interest to these microbes—although it would depend on how bioavailable the iron was, Christner allows.

To the extent that any subglacial Mars microbes (that may or may not exist) might resemble extremophile microbes on Earth, they probably wouldn’t have much interest in the cucumber, either.

There’s one more reason, though, that trying to make pickles with Mars brine wouldn’t work out. Assuming that the salts that have made their way into the brine are similar to the salts that have been found on the planet’s surface, they’re likely to be perchlorate, a type of chemical compound containing an ion made up of chlorine and oxygen. Perchlorates exist on Earth, too, and they’re commonly used in “rocket propellants, munitions, fireworks, airbag initiators for vehicles, matches, signal flares” and fertilizers, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. These compounds are not what you want to be putting into your body: Prolonged exposure to sodium perchlorate, through swallowing, for instance, can cause organ damage.

Pickling in Martian water, then, is not likely to be a success. If we ever do figure out how to grow food on the Red Planet and we want to preserve it, we’ll need some good old Earth-style water and microbes to do the trick. Cultivated in the right fashion, though, who knows what wonders Martian microbes might work on our food? Perhaps they’ll work some chemical magic that will result in a new type of delicacy never encountered on Earth. (Assuming, of course, that they don’t kill us first.)

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook