Inside the Midwest’s State Fair Historical Recipe Contest

From biscuits to cherry pie, these award-winning dishes tell family stories dating back to the 1800s.

Beth Campbell remembers long days working on family farms as a child. Along with her parents and siblings, as well as her aunts, uncles, and cousins, she would go from one farm to the next to help with chores. Along with milking cows before and after school, she’d often find herself grinding green tomatoes in a large cement basement. But the work was not without reward: Her mother and grandmother would transform the fruits of her labor into mincemeat cake.

Decades later, Campbell’s family recipe for the cake, a rich, sweet-and-spiced confection coated in chopped walnuts and caramel icing, won first prize at the 2014 Wisconsin State Fair Heirloom Recipe Competition. The cake earned high marks for its flavor, but what really pushed Campbell to blue-ribbon glory was the story behind it. Campbell’s narrative, of a tough grandpa who had his grown children work to “pay for their childhood” and nostalgic descriptions of her family banding together to spin scraps into delicacies, was the judges’ favorite that year.

“I remember the smell of the mincemeat filling cooking down, ready to be put into jars for processing, and the whole house filled with the wonderful smells of the end of the growing season, with winter not being too far away,” she writes in her contest submission. Though mincemeat has largely disappeared from American tables, Campbell finds the time-consuming project worthwhile because it helps her connect with her now-deceased mother and grandmother.

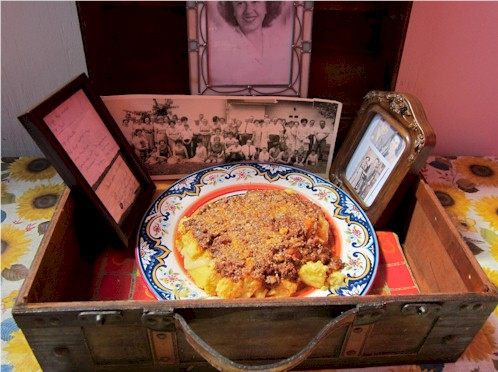

It’s this powerful connection to the past that spurred Catherine Lambrecht, president of the Greater Midwest Foodways Alliance, to start the Heirloom Recipe Competition in 2009. Run by the Alliance, the contest takes place at state fairs across the Midwest. All entries must be made-from-scratch family recipes, accompanied by personal narratives, that date back to before 1950. The story behind each dish makes up the bulk of one’s score (50 percent), while execution accounts for 40 percent and appearance for 10 percent. The latter includes any mementos that tell its story, such as photos, the worn original recipe card, or an aunt’s beloved rolling pin.

Lambrecht started the project to encourage people to preserve their family recipes before it was too late. For her, this is personal: When her grandmother died, she took her famous spaetzle-and-sauerkraut recipe to the grave. It took years of experimenting for Lambrecht to finally recapture the dish.

“I hear it all the time,” she says. “There was something their mother made or their grandmother made and they really enjoyed it. Then when that person disappears, they have no clue how it was made. It’s like this itch that can’t be satisfied.”

Over 11 years, the contest has collected recipes dating as far back as 1832 and covering nine states. Many entries highlight the bounty of the land, bursting with freshly foraged native greens, sweet seasonal fruit, milk from the family cow, and fish from the nearby river.

Shelby McCreedy admits she didn’t appreciate the value of local, fresh food as a child. “Every time I asked to go to town to eat,” she writes in the entry for her award-winning cherry pie, “my Grandma reminded me that if they didn’t raise it or grow it on the farm, I didn’t need to eat it. (I thought this was child abuse!)”

Other recipes tell stories of immigrant communities, such as the buns baked by the German Mennonites who turned Kansas into a wheat-producing powerhouse, or the cherry coffee cake that offers a glimpse into early Czech communities in Illinois. Some heirloom immigrant recipes preserve dishes that have since disappeared in their countries of origin. “Food is a time capsule like that,” Lambrecht says.

While the Heirloom Recipe Competition has been put on hold this year due to COVID-19, that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy some of its winning dishes. Each of the below recipes reveals how many rich stories lurk in America’s soil, in its tattered cookbooks, on its stained index cards, and on its tables. Even if you can’t travel this year, you can still wander across state lines and across history with these recipes and the stories behind them.

Grandma’s Mincemeat Cake With Caramel Icing

First Prize, 2014 Wisconsin State Fair

Beth Campbell, Belleville, Wisconsin

Campbell’s full story can be found on the Greater Midwest Foodways Alliance website. The whole cake should yield about 14 to 20 slices. It’s very rich, so she recommends slicing small.

For the mincemeat:

3 pounds green tomatoes

3 pounds apples

2 pounds raisins (plumped in hot water for 1/2 hour)

8 cups brown sugar

2 tablespoon salt

1 cup suet

1 cup vinegar

2 tablespoon cinnamon

2 teaspoon ground cloves

1 teaspoon nutmeg

For the batter:

2 cups sugar

1/2 cup cooking oil (I would suspect that my grandma used melted lard, but I used vegetable cooking oil)

4 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

2 cups buttermilk

1 pint (2 cups) mincemeat

1 cup chopped walnuts (of course my grandma would have used black walnuts from the walnut trees that we dried, shucked and picked)

1/4 cup sourmash (bourbon)

For the icing:

1 teaspoon vanilla

2 cups brown sugar

1 pinch of salt

1 stick of butter

5 tablespoons of cream

1/4 teaspoon baking powder

For the mincemeat: This recipe comes from the 1907 Ladies Aid Cookbook of our church that my grandma and grandpa’s families founded.

Grind the green tomatoes. Pour boiling water over them twice, draining each time. Grind the apples and suet. Mix all the rest of the ingredients and boil until thick. (It takes about an hour.) Seal everything in sterilized jars while it’s still hot and process it in a hot water bath for at least 30 minutes until the jars seal.

For the batter:

Combine the sugar and cooking oil; mix well. Sift together the flour, soda, and salt. Add the buttermilk to the sugar mixture. Add the dry ingredients alternately and beat well. Stir in the mincemeat, sourmash bourbon, and the nuts. Turn the batter into two greased 9-inch cake pans. Bake at 325 degrees for 1 hour or longer if necessary. Test with a toothpick stuck in the middle of the cake that comes out clean for doneness.

For the icing:

Combine all of the ingredients and boil in a saucepan. Let boil for 5–7 minutes. Beat in the baking powder with a spoon; add the vanilla. Let it cool slightly. Beat until it gets thick. Add the powdered sugar until you get a nice spreading consistency to spread on the cake. Frosting dries quickly so you need to work fast with it before it hardens. (Grandma wasn’t a fancy cake decorator but would put finely chopped walnuts around the cake and drizzle some of the frosting on the edges, so in keeping with tradition—I did the same!)

Peanut Brittle

Second Prize, 2011 Illinois State Fair

Amy Wertheim, Bloomington, Illinois

In 2004, Amy Wertheim saw her family’s candy store burn to the ground. Along with equipment and more than 500 pounds of treats, she lost something far more precious: her grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ handwritten recipes. “Of everything we lost, that was the most devastating,” she writes.

One way Wertheim filled the void was by collecting cookbooks. At an auction in 2010, she picked up a weathered collection of personal recipes written down for a new bride. “As I turned the pages, I started seeing names I recognized … and then I saw the name, Mother Hoblit.” It was her great-grandmother’s family nickname. She also noticed something stuck in the book’s folds. “My hands were shaking as I unfolded the crackling paper … there, in my Great-Grandmother’s handwriting, was our lost peanut brittle recipe.”

Wertheim’s presentation at the Illinois State Fair featured the book, along with the handwritten peanut brittle recipe and a plate of the sweet, crunchy treat, a fixture at family and church gatherings for generations. “I can only speculate why out of all the cookbooks I picked up that one … We still cannot believe that after all this time, the book and the recipe found its way home.”

1 1/2 cups sugar

2/3 cup glucose (Karo corn syrup for the home cook)

1 cup water

1/2 pound unroasted Spanish peanuts

1 teaspoon butter

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 teaspoon vanilla

1. Cook the sugar, glucose, and water until it makes a soft ball in a water bath (drop a few bits of syrup in water and if it balls, then it’s at a soft ball stage).

2. Add the peanuts and butter to the syrup and cook until golden brown. Add the soda and vanilla, stirring quickly, and pour onto a marble slab or buttered platter. Allow it to cool slightly, and then stretch until thin and brittle.

3. Break into pieces, and enjoy. Recipe makes enough for four people and can be doubled or tripled as desired.

Grandma’s Cherry Pie

First Prize, 2014 Iowa State Fair

Shelby McCreedy, Atlantic, Iowa

When it came to cooking, Shelby McCreedy’s grandmother taught her the beauty of well-executed simplicity. Hit hard by the Great Depression, her grandparents were adept at spinning minimal resources into deliciousness. Grandma’s cherry pie was a prime example, bursting with tart fruit plucked and pitted right before use and a crust rich with lard made from the family’s hogs.

“No need to be fancy and put more things in the pie than was necessary,” McCreedy writes. “‘Let the fruit do the work, and don’t mess it up!’ Grandma constantly reminded me the basics were good enough.”

Her grandmother’s handwritten recipe was equally no-frills, scribbled in the margins of a tattered 1930s church cookbook that lost its back cover. Along with pie, she’d added her recipes for fried chicken, dinner rolls, and cinnamon rolls. “It was like a maze to follow as Grandma had written in margins, up and down sides of pages, upside down, and not all of the directions were complete.”

McCreedy keeps her now-deceased grandmother’s memory alive with these recipes. She’s even planted a cherry tree on her property and taught her daughter the value of hours spent picking and pitting. “I wanted to make sure I could continue to make her cherry pie exactly the way I was taught.”

For the crust:

2 cups flour

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup good, quality lard

1 egg

4–5 tablespoons ice water

For the filling:

4 cups tart pie cherries

1/4 cup tapioca

1 1/3 cups sugar

1 teaspoon lemon juice

2 tablespoons butter

1. To make the crust, combine the flour and salt in a bowl. Cut in the lard until crumbles form. Add the egg and water and mix until a ball forms. Chill the dough. Remove and cut the dough in half, reserving one half for the top crust. Roll out the crust and place in bottom of a 9-inch pie plate. Trim the edges.

2. In a bowl, mix the cherries and lemon juice. In a separate bowl, combine the sugar and tapioca. Combine with the cherries, mixing gently to coat. [Pour the mixture into the pie crust.] Dot with butter.

3. Roll out the remaining crust and place over the top of the pie. Vent the top and crimp the edges. Brush the top of the crust with milk and sprinkle with sugar.

4. Bake in a moderate (350-degree) oven for one hour. Cool before serving.

Zwieback

First Prize, 2012 Kansas State Fair

Jane Fry, Elk Falls, Kansas

Jane Fry grew up eating zwieback, a double-stacked bun enjoyed by Mennonite communities in Kansas. She remembers her family tucking into the fluffy, snowman-shaped buns during vaspa, or Sunday lunch, and dunking them in coffee or a barley-based coffee substitute known as “prips.”

“The proper way to eat a zwieback was to pull off the top ball, whether you ate that first or saved it till last was a personal preference,” writes Fry. “Then with the ball removed, it left a rounded indention for jelly or honey or just plain butter. I remember as a child having guests for dinner when someone who had never eaten zwieback before took a knife and just cut it in half. There were several gasps, and the children quickly told the guest the proper way to enjoy the double bun.”

The route that Mennonites took to the Sunflower State was a circuitous one. In the 1760s, Catherine the Great offered tax and military exemptions to lure skilled Mennonite farmers from Germany to Russia, where she hoped they would work unfarmed land. After Alexander II revoked the military exemption a century later, the pacifist communities sought a new home. Many settled in North America, bringing with them kernels of Turkey Red Wheat and grain-farming expertise that helped create Kansas’s now-booming wheat industry, along with these delicious buns.

2 cups scalded milk

1 cup lukewarm water

2 teaspoons sugar

2 teaspoons salt

4 tablespoons sugar

1 cup lard (or shortening)

2 eggs

1 yeast cake (1 tablespoon dry yeast)

1 3/4 cups whole wheat flour

8 1/4 cups sifted bread flour

1. Scald the milk, and add the lard, salt, and 4 tablespoons of sugar.

2. Crumble the yeast in a small bowl, then add 2 teaspoons of sugar and 1 cup of lukewarm water. Set in a warm place until spongy. (I did this with 1 tablespoon yeast.) Add the yeast mixture and beaten eggs to the lukewarm milk in a mixing bowl. Mix well and stir in the flour gradually.

3. Knead the dough until very soft and smooth. Cover and let it rise in a warm place until it doubles in bulk (1 hour). Pinch off small balls of dough the size of a small egg (2 ounces). Place these 1 inch apart on a greased pan. Put a similar ball, but slightly smaller, on top of the bottom ball (1 ounce). Press down with your thumb. Let them rise until they double in bulk.

4. Bake at 350–375 degrees for 15–20 minutes. Recipe yields approximately three dozen buns.

Biscuits and Wild Blackberry Jam

First Prize, 2014 Indiana State Fair

Beverley Weaver Rossell, Morgantown, Indiana

Beverly Weaver Rossell remembers the sumptuous spreads her great-aunt Veryne laid out for her great-uncle and the hired hands who worked their 200-acre farm.

“There were rarely leftovers, and her melt-in-your-mouth baking powder biscuits were snatched up before the meat platters and deep bowls of potatoes and gravy fully made their way around the table,” she writes in her contest submission.

Most of the biscuits’ ingredients came from the farm: cream and freshly churned butter from the Jersey cows, lard, locally milled wheat, and jams and jellies made from fresh fruit. The latter included what Veryne dubbed “shadeberry spread,” because the largest wild blackberries grew in the shade.

“Growing up in our rural farming community in the ’50s was such a good thing—a time of innocence and simplicity,” Rossell writes. “At 10 years of age, I was fearlessly walking down the quarter-mile livestock lane that led to the common watering hole, picking dead-ripe blackberries growing intermittently on the sagging cattle fence for Aunt Veryne’s dumplings, jams, and fruit butter.”

Anyone who wishes to truly test themselves with Great-aunt Veryne’s made-from-scratch approach can also attempt her homemade lard, flour, and butter. Instructions for these are available on the Greater Midwest Foodways Alliance website.

Baking Powder Biscuits

2 cups unbleached all-purpose flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

2 tablespoons sugar

1/3 cup frozen lard cut into 1/2-inch pieces

1 1/2 cups cream

2 tablespoons melted butter for brushing biscuit tops

Combine the dry ingredients; cut in the lard to make pea-size granules. Add the cream; mix just to combine. Roll it out onto a floured hard surface; knead 8–10 times. Cut with a floured biscuit cutter or sharp knife. Brush with melted butter. Bake at 450 degrees for 15 minutes or until golden.

Old-Fashioned Wild Blackberry Jam

4 cups fresh blackberries

3 cups sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon lemon juice

Combine the ingredients in a large heavy saucepan; cook over medium heat until the berries are tender (15–20 minutes). Run the mixture through a fine sieve. Pour into sterilized jars. The jam will thicken as it sets.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook