The Man Who Built 40 Castles Around a Little German Town

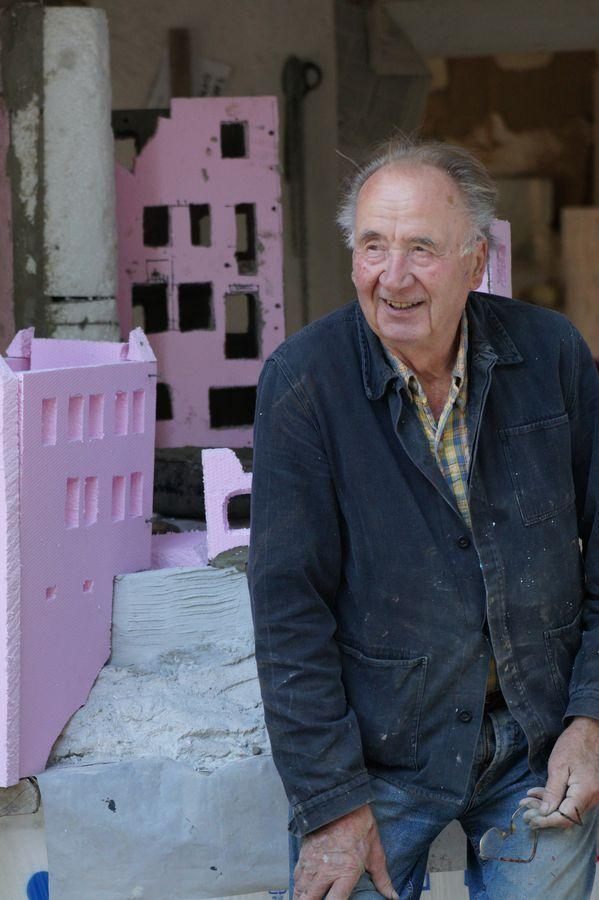

Günther Beinert’s regal miniatures appear all over Gerbstedt (population: 3,000).

You notice the castles the minute you arrive in Gerbstedt, a quiet little town in Germany’s Saxony-Anhalt state, an hour’s drive from Leipzig. Elaborately constructed miniature castles, replete with tiny windows, shrubs, and dwellers in historical attire, greet you at different spots around town—outside the supermarket, in front of the church, on people’s front lawns. It’s an open-air museum of sorts spanning the entire area.

“I built my first castle in 1949, after the war had ended,” says Günther Beinert, the 87-year-old creator of these miniature works. He describes breaking down a wall at his parents’ old house, reassembling the materials with a mixture of ash and sand, and building a small castle from imagination. “That was my first work.”

Born in Gerbstedt in 1933, Beinert is a professional bricklayer. He began constructing miniature castles in his spare time, he says, eventually amassing so many that he ran out of storage space in his workshop. A call to the municipality followed, to ask if there was room to install his creations outside. “And that’s how it all began,” he says. Today, 40 miniature castles adorn Gerbstedt. Along with them, Beinert has brought to life replicas of knights, and a series of trains that occupy the site of the now-defunct train station.

“It was a passion that I wanted to pursue professionally,” he says, referring to his miniatures. “And that’s why I became a bricklayer. Through this I got more involved in [my craft].” He visited a few castles over time but it was always the masonry that interested him, he says, noting the “laborious task of construction, how these handworkers painstakingly built [them].”

“I found a book about castles—it was one of these encyclopedias, a catalog of cigarette boxes,” he says. At the turn of the 20th century, German cigarette companies began issuing collectible picture cards with their products. In the 1930s, tobacco company Reemtsma introduced themed albums—on topics such as German history, the 1936 Olympics, and exotic animals—containing descriptive texts that buyers could paste the corresponding picture cards into. Affordably priced, these albums allowed people from all walks of life to create extensive home reference libraries. They would go on to be used as a tool for political propaganda, but it was the pictures from one of these books that Beinert initially relied on to build his castles.

At times, his creations provided a means of subsistence. For a good portion of Beinert’s life, until the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989-90, Gerbstedt was part of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). Today, he still lives with his wife in the home that he and two fellow bricklayers built, at the site of an old barn in 1962. He recounts the struggles of life in East Germany, and says that he began trading his castles for things they needed, such as a garage door or spare parts for the car. “The motto was—you make something, you get something,” he says.

Beinert’s fairly innocuous passion occasionally landed him in trouble with the authorities, as his miniatures predominantly depicted the castles of West Germany. “I was ratted out for placing black, red, and gold flags on these castles without the emblem,” he recalls, referring to the national emblem of East Germany, which distinguished it from the flag of West Germany (and Germany after reunification). “I was disciplined by the [Socialist Unity Party] and told I glorified feudalism, which was complete nonsense.”

“I was a nobody, I only gained joy from my craft,” Beinert says. “I recreated West German castles because we couldn’t visit them—that’s why I brought the West to Gerbstedt.”

Gerbstedt, with a population of approximately 3,000, boasts a surprisingly rich history stretching back over a thousand years, says Ulrich Elster, who regularly offers guided tours of the local museum. It’s a mere nine miles from Eisleben, the 1483 birthplace of Protestant Reformation instigator Martin Luther. In the early 12th century, the Battle of Welfesholz between the Holy Roman Empire and a rebellious Saxon army played out in the region. And for nearly 600 years, says Elster, the town was the site of a prominent Benedictine monastery.

In front of the Gerbstedt Castle stands the miniature Mansfeld Castle, an intricate replica of its historic counterpart in the neighboring town of Mansfeld. Weighing 44.1 US tons (40 metric tons), it is Beinert’s biggest work, and required 18 months and around 100,000 stones to complete.

Since retirement, Beinert has had more free time on his hands, he says. During his younger years, he juggled bricklaying and his creative pursuits. “I have to praise my wife, she had to finally accept that I was in the workshop all the time. [In those days] I came home, sat at the table, ate, and went straight to the workshop,” he recalls. “Now [my wife and I] are happy if we can just watch something together, for instance on the television. We have done all that was possible in our lives, and we are content.”

The idea of creating a Burgenwanderweg—or castle hiking trail—emerged in 2015, says Alexandra Preiss, a Gerbstedt City Council representative. Residents found that tourists were disembarking from tour buses to take photographs with the miniature castles, she says, and were curious about the location of their real-life counterparts. And so, two years later, with the help of EU funding, the Gerbstedt castle walk was inaugurated, connecting all 40 of Beinert’s extraordinary miniature castles and providing succinct information about each one’s history.

These days, Beinert continues to head to his workshop, and is in the midst of wrapping up another castle—a fictional one that a colleague discovered on the internet. He doesn’t know if the miniature will be installed anywhere, but merely looking at it brings him joy. “This will most likely be my last creation,” he says. “My fingers don’t work the way I intend them to anymore, although that’s a different story. But this castle has given me strength again.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook