Did Mooncakes Help the Chinese Overthrow the Mongols?

On the enduring power of myth and metaphor.

After 88 years under Mongol rule, the spirits of Han Chinese families were at an all-time low. Every aspect of their lives was at the mercy of their Mongol rulers who were, mostly, not terribly merciful. Due to fears about uprisings, the Han couldn’t meet in groups. Possessing weapons was out, too, even meat and vegetable cleavers, which were rationed—one for every ten families. Mongol guards were everywhere, keeping an eye on that potentially nefarious chopper. Spies were even stationed in each house, while famine and poverty scratched at the door.

And there were worse abuses, or so the stories say. Young sons were molested, daughters were violently “deflowered” before their weddings. A Mongol law demanded the thumbs of all Chinese boys to be mutilated at birth so they would be incapable of drawing a bow.

By 1368, the stories continue, the time was ripe for an uprising. Zhu Yuanzhang, the man who would one day be emperor of China’s Ming Dynasty, was then a young man born to a desperately poor Han Chinese peasant family. However, he had a brilliant friend, Liu Bowen, to aid his rise to prominence and power. Liu was a poet and philosopher—and a remarkable strategist. The Mid-Autumn Festival was approaching, the time when every family would traditionally exchange and eat pastries called mooncakes.

Liu sent men to every corner of the three prefectures under Mongol rule, where each visited pastry shops and filed orders for millions and millions of mooncakes. In each one, it is said, they slipped a piece of paper that said: “The spiritual illuminaries are hidden in the darkness, they are secretly helping people to defreeze the icy cold. Take action on the midnight hour, let us kill the housekeeping masters all together!” And so they did, on the night of the Moon Festival, and so the Chinese were liberated.

At least, that’s one version of the story. Another says that the message read, less poetically, ‘‘Kill the Tartars on New Year’s Eve!’ (The Mongols did not read Chinese, and so remained in the dark about the mooncake messages.) Or perhaps the message was written on the rice-paper placed under the cakes. Maybe the message had been coded, and assembled by combining multiple mooncakes. Was it definitely mooncakes? It might have been instructions on medicine sold door-to-door. No, wait, no message whatsoever—just the power of rumor, whispered from household to household.

All these stories, collated by the late scholar of Chinese history Hok-Lam Chan, are just stories. “It’s preposterous,” he writes, “to cast [Liu] as the instigator of the uprising and credit him with the plan to conceal the messages calling for rebellion in the filling of mooncakes.”

We do know that the Mongols ruled over the Han Chinese, and that, over multiple decades in the second half of the 14th century, there was an uprising that led to Zhu Yuanzhang seizing control and establishing the Ming Dynasty. But almost everything else in this amalgamation of stories, from the thumbs to the messages to the mooncakes, is entirely untrue. Still, the story is often repeated as fact, or as an unverified-but-probably-true story that somehow escapes the “orthodox” histories.

But what are mooncakes? Often described as a cultural equivalent to Western holiday fruitcake, mooncakes are a seasonal dessert bought by millions of Chinese families to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival. Round and golden like the harvest moon, the cakes consist of a filled pastry case molded into the shape of a chrysanthemum, about three or four inches in diameter. Not everyone likes them. They’re extremely dense—not because they’re made of moon, but because they enclose a thick, rich filling of red beans, dates, or lotus seed paste. There are regional varieties, too. Cantonese mooncakes, for example, conceal a whole salted duck egg yolk, as rich and round as the late September full moon, within their shell.

Eating them is a celebration of the moon and the harvest. It’s also an important cultural transaction: Businessmen spend the equivalent of hundreds of dollars on high-end versions. The especially luxurious ones come in boxes decorated with silk, paintings, and sometimes real gold. (Each contains either four or eight mooncakes, with more superfluous individual wrappings.) Every year, close to $375 million is spent on their packaging alone. These expensive gifts sometimes blur the line between business “gifting” and outright bribery.

In 2013, the Chinese government cracked down on what it perceived as out-of-control expenditures by government officials who used public money to gift mooncakes to business associates. (An official party circular from President Xi Jinping said, according to CNN, “Superior departments and officials should seize on the trend of these luxurious celebrations and be courageous enough to spot and rectify decadent behavior in a timely manner while setting an example themselves.”) Like fruitcakes, millions, too, get chucked out. In Hong Kong alone, an estimated 2.5 million mooncakes were thrown away after the 2013 Mid-Autumn Festival. That’s one for every three people living on the island.

There is plenty of Chinese mythos around the Moon and, by extension, around mooncakes—such as Old Man Under the Moon or the Lady of the Moon. But only the Mongol legend is repeated, at least occasionally, as being true. The reason, says Chan, may relate to historical Chinese nationalism. In the late Qing period, which ended around the beginning of World War I, written accounts of the story began to spread anew. In those stories, the Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic group in China, were being ruled by a different ethnic minority—the Manchus (who dominated the Qing Dynasty).

It’s likely, Chan says, that the stories were written and shared by members of anti-Manchu secret societies. By sharing the stories as fact, they remade the collective memory of the Han Chinese rebellion against the Mongols. This version of history put the uprising in the hands of the people, which stirred up nationalistic fervor. It wasn’t hard for Han readers at the time to link their experience under the Manchus to their ancestors’ trials under the Mongols. Liu Bowen, in turn, became a relatable, inspirational, contemporary hero.

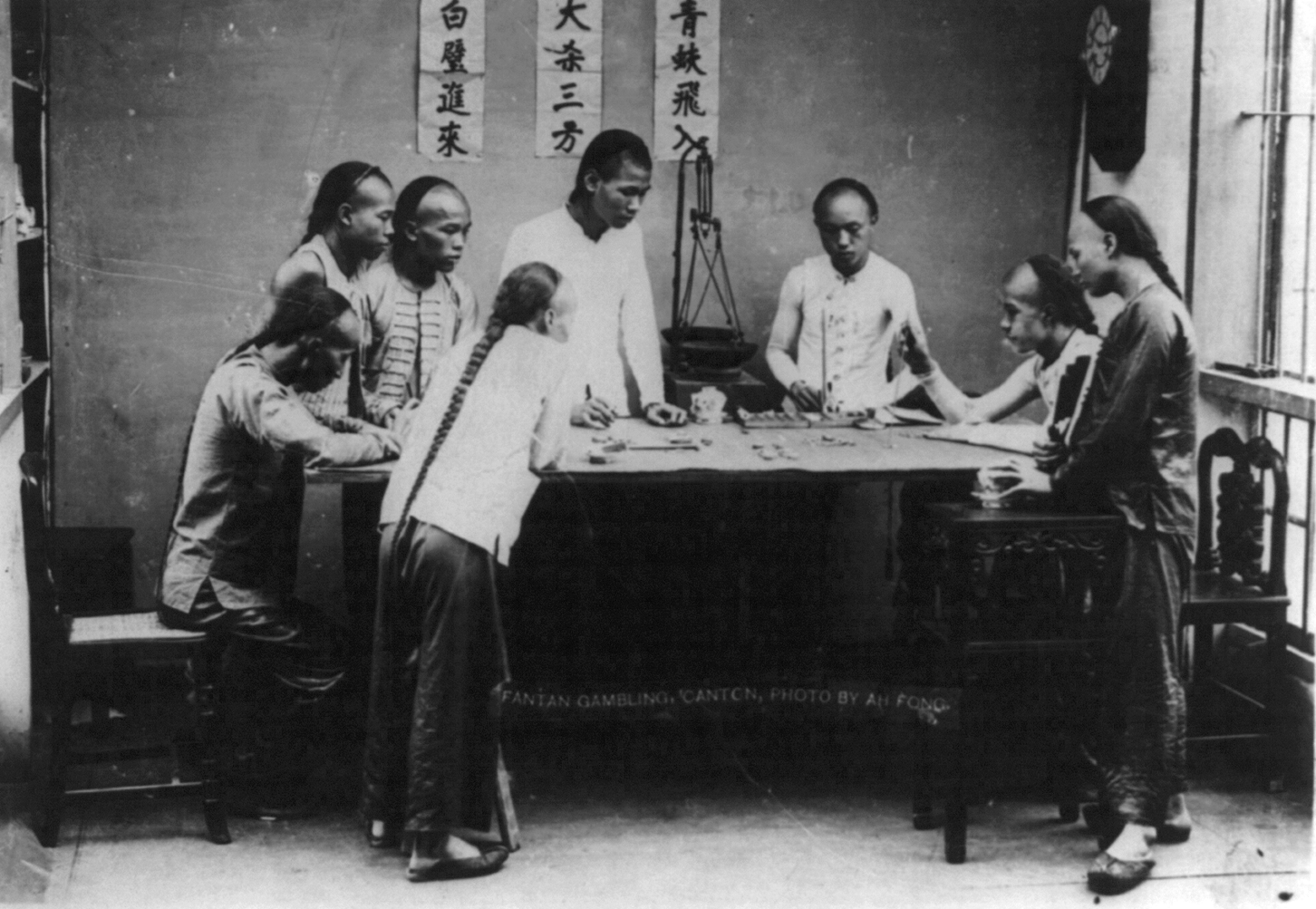

Chinese repression under the Manchus was less cartoonishly horrible than the fictional Mongol version, though it was still felt acutely. One particularly striking example, which makes it into many propaganda images from the time, was the Manchu hairstyle that Han Chinese men were obliged to don. Known as a “queue” or “cue,” it consists of a partially shaved head with a long braid cascading from the top of the crown. Traditionally, Han Chinese men and women did not cut their hair at all, and instead wound it into a topknot. But from 1644, when Beijing was sacked by the Qing, the queue was a compulsory sign of submission to Manchu rule.

The mooncakes’ message might not played a direct role in overthrowing the Mongols, but the idea of it did play a small part in propagating what Chan describes as the “‘expel the Tartars, restore Chinese rule’ manifesto of the Han nationalist revolution.” This same sentiment, in turn, led to the overthrow of the Manchus. The story may be fictional, but the impact of the propaganda is real, and was harnessed in a very elegant way by anti-Qing campaigners. Political opposition of this sort had simmered for centuries, in pockets of resistance and occasional uprisings. (Between 1850 and 1863, for example, the Taiping Rebellion led to tens of millions of people dying in clashes between rebels from southern China and the Manchu rulers—by some estimates, twice the death toll of World War I.)

One of the definitive events of this opposition, the Wuchang Uprising, took place in October 1911. The conflict began due to a kerfuffle over railway nationalization, but it snowballed into a coup. In time, this came to be known as the Xinhai Revolution, and led to the 1912 abdication of the six-year-old Manchu emperor, the end of the Qing Dynasty, and the start of the Republic of China. The mooncakes’ role in this (as instruments of propaganda and symbols of Han nationalism) may have been limited, but it was more real and tangible than its effect on the overthrow of the Mongols some 600 years earlier.

Contemporary Chinese diners tend not to think about the political implications of their mooncakes. Squabbles about fillings and crusts are far more common. (The hashtag #五仁滾出月餅界, which was trending in 2013, called for a ban on a filling known as “five nuts.”) Curiously, the Cantonese variety with duck egg yolk has become especially popular over the last century.

That’s not to say that mooncakes have had no contemporary political import whatsoever. Sometimes, they appear in overt, anti-China messages. In the 1950s, a bakery in Taipei, Taiwan (considered a rebel province of China) rechristened its festive offerings “anti-communism and fight Russia moon cake” and called on customers to “develop the righteous spirit of the ethnic group.” More recently, in 2014, Umbrella Revolution dissidents in Hong Kong baked political messages into the exterior of mooncakes. Still, it’s still far more common for them to be used by Chinese embassies, diplomats, and officials as tasty vessels for national pride (and red beans). Whatever the purpose, there’s more lurking underneath this crusty exterior than duck eggs, five nuts, or lotus seed paste.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook