A Time-Twisting Visit to the Museum of Capitalism

How artists and curators are attempting to defamiliarize America’s current economic era.

In the back corner of the gallery, three chunks of amber glow under a spotlight. I squint at one and make out a couple of dark shapes. I’m expecting stuck bugs or plant matter, relics of some prehistoric age. Instead, I see an iPod Nano and a scrap of a fun-sized Butterfinger wrapper: relics very much of this century.

“They remind me of Jurassic Park,” says curator Abigail Satinsky, looking at the art (Amber Pieces, by Evan Yee) over my shoulder. She and I are the only ones there. I have a series of visions in which future scientists carefully remove the preserved gadget, splice its material into a chicken egg, and step back to wait for their creation to hatch, not realizing the havoc they could wreak.

Such is the time-warping effect of the Museum of Capitalism, an art project that seeks to provide a new view on America’s current economic era by pretending it’s over. A collection of both “artworks and artifacts”—as well as works, like Amber Pieces, that blur the line between the two—function together to create the necessary distance. As the exhibit’s entrance text puts it, “We should not have to wait until things have ended in order to examine them … from the very beginning[,] we should look at them the way we’re taught to look at things in museums.”

The Museum of Capitalism is the creation of Timothy Furstnau and Andrea Steves, designers and curators who work together under the name FICTILIS. The first version of the museum opened in Oakland in 2015, in an abandoned warehouse. This past week, it became a franchise: The incarnation I visited is in Boston, at the Grossman Gallery, part of the School for the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University.

While it shares an ethos (and some exhibits) with the Oakland version, Satinsky says it is its own beast, tuned to the particular rhythms of its new location. (For instance, a machine by Blake Fall-Conroy dispenses exactly $11 every hour in pennies—Boston’s minimum wage—as long as you keep turning a crank.) Another exhibition is coming to New York later this year or next.

The conceit of each of them is the same: Once you enter the gallery, capitalism has ended. There is no hint of what might have replaced it—all you know is that you are in the future, trying to learn about how things used to be. In the same way other museums might present a representative slice of the Renaissance or the Pharaonic Period, the exhibits carefully lay out what the curators consider to be the era’s most telling creations.

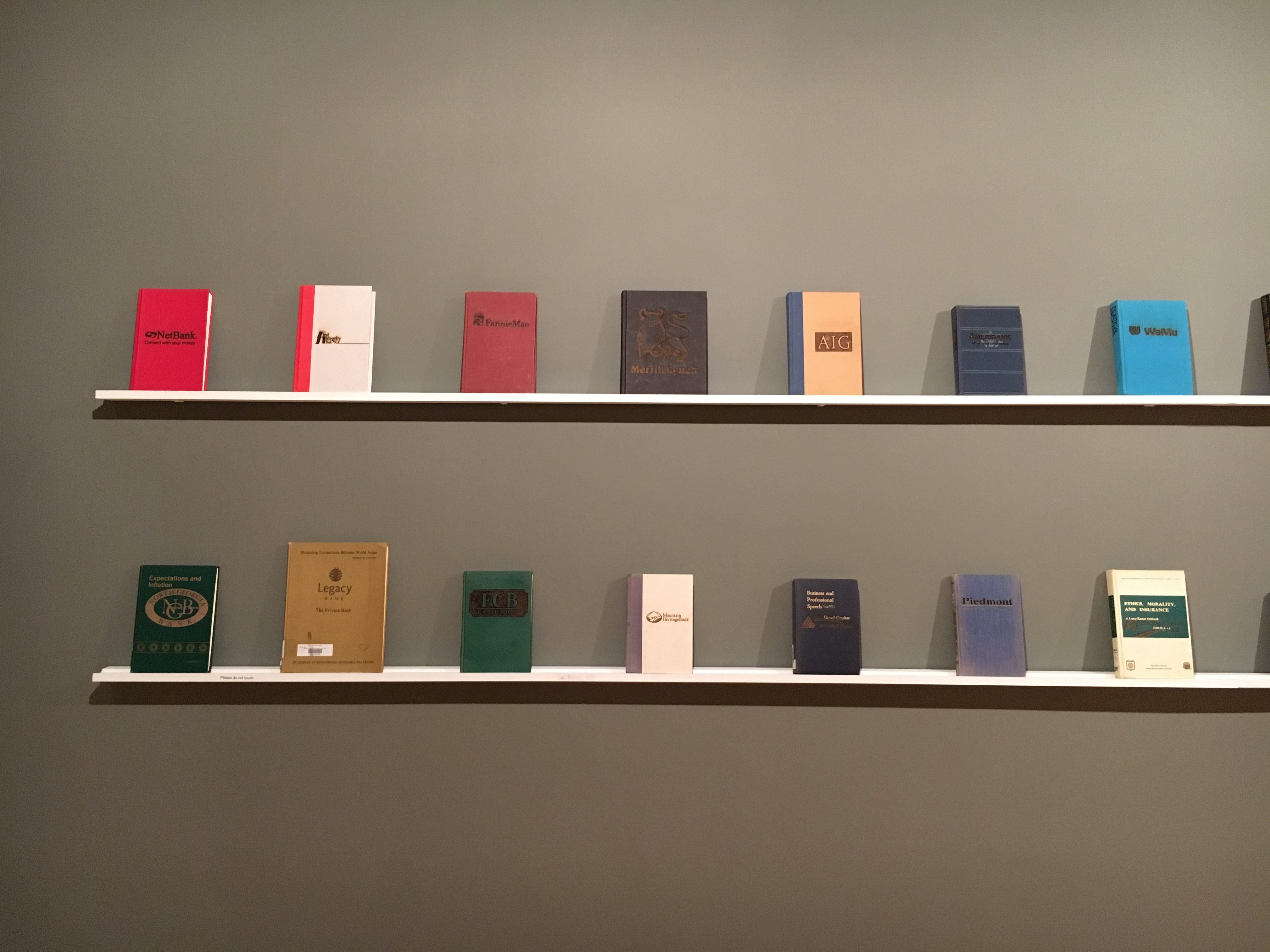

One case in the Grossman Gallery contains a set of mass-produced trading cards themed around Operation Desert Storm, the 1991 American-led Gulf War military operation. (The cards were “the first ever issued on a war while it was in progress,” the accompanying text explains). A wall is lined with dozens of financial planning books, all branded with the names of small banks that have been absorbed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

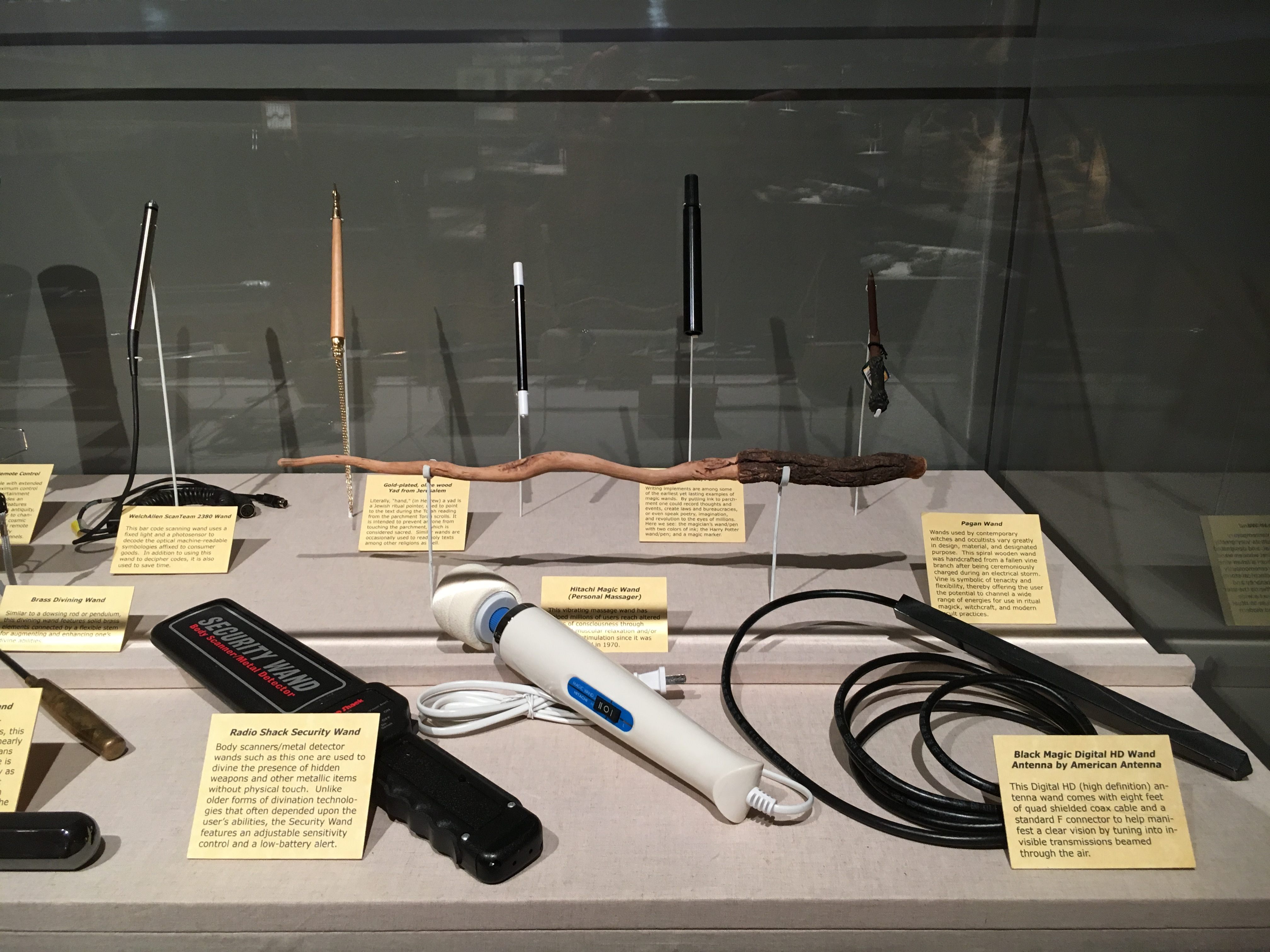

Other works attempt to contextualize such artifacts by taking a longer view. Three bags by Jordan Bennet recreate plastic Target, Walmart, and 99-cent-store bags in moose hide, the plastic equivalent of a few centuries ago. Another case by Center for Tactical Magic* is filled with a centuries-spanning rundown of powerful oblong objects, from magic wands to pens to security scanners and TV remotes. “Like so many useful technologies over the last few years, wands have gone through changes, becoming more and more … specialized,” reads the accompanying text. “In many cases, they are so removed from their origins that one easily forgets their roots.”

These exhibit descriptions and other written materials strike a tone of educated remove. They summarize, condense, and theorize. “In globalized capitalism, consumption of products typically occurred long distances from their place of origin, and people … often selected products based on their visual appearance,” begins the caption next to Maia Chao’s In the Shell of the Old, an artwork made of polystyrene packaging in a stunning variety of shapes. These people, it adds, were “defined by their buying habits and referred to as ‘consumers.’”

All of these tricks and juxtapositions encourage us to jump through time, helping us to imagine the ways in which our economic system might define us in retrospect. At the same time, the broadness of their conclusions reminds us of the flattening involved in all efforts to explain history: When we try to look in on people from the past, what does our vantage point show us that they couldn’t understand? And what are we missing?

As in those other museums, the most telling exhibits are those that allowed moments for individual humanity. A collection of retirement letters—addressed to a man named Bill Pollock on the occasion of his retirement from IBM, and collated by FICTILIS— “Hey, what is this retirement crap at such a young and vital age?” wrote one friend, Chuck. “Weep late and worry not at all” wrote another, Harold. As I left, I looked back at the empty hall, and realized that the emptiness itself was part of the experience. The day after Labor Day, no one has time to go to the Museum of Capitalism, because everybody is at work.

*Correction: This article previously credited the wand case incorrectly. It is by Center for Tactical Magic.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook