Why Can’t People Stop Touching Museum Exhibits?

After years of watching, one researcher thinks she’s got the answer.

You’re walking through a museum when a piece of art seems to call out to you. Maybe it’s a bowl, smooth and detailed with shiny gold leaf. Maybe it’s a statue of Venus, her hand outstretched. You walk over to this enticing object. You lean in as close as you can.

Why is it so tempting to just reach out and touch it?

Fiona Candlin, a professor of museology at Birkbeck College in London, has been asking this question for over 20 years. Candlin was working at the Tate Liverpool in the early 2000s when the U.K.’s Disability Discrimination Act first passed. Thanks to the new law, museums in the country were starting to think harder about how to make exhibits more accessible to the visually impaired, and Candlin found herself dissatisfied with the results.

“I thought a lot of the stuff they put on was just so token,” she says. “It didn’t begin to think about how we might encounter things through touching them.” So Candlin embarked on her own course of observational research. In short, she says, “I spent a lot of time sitting in galleries, watching people touch things.”

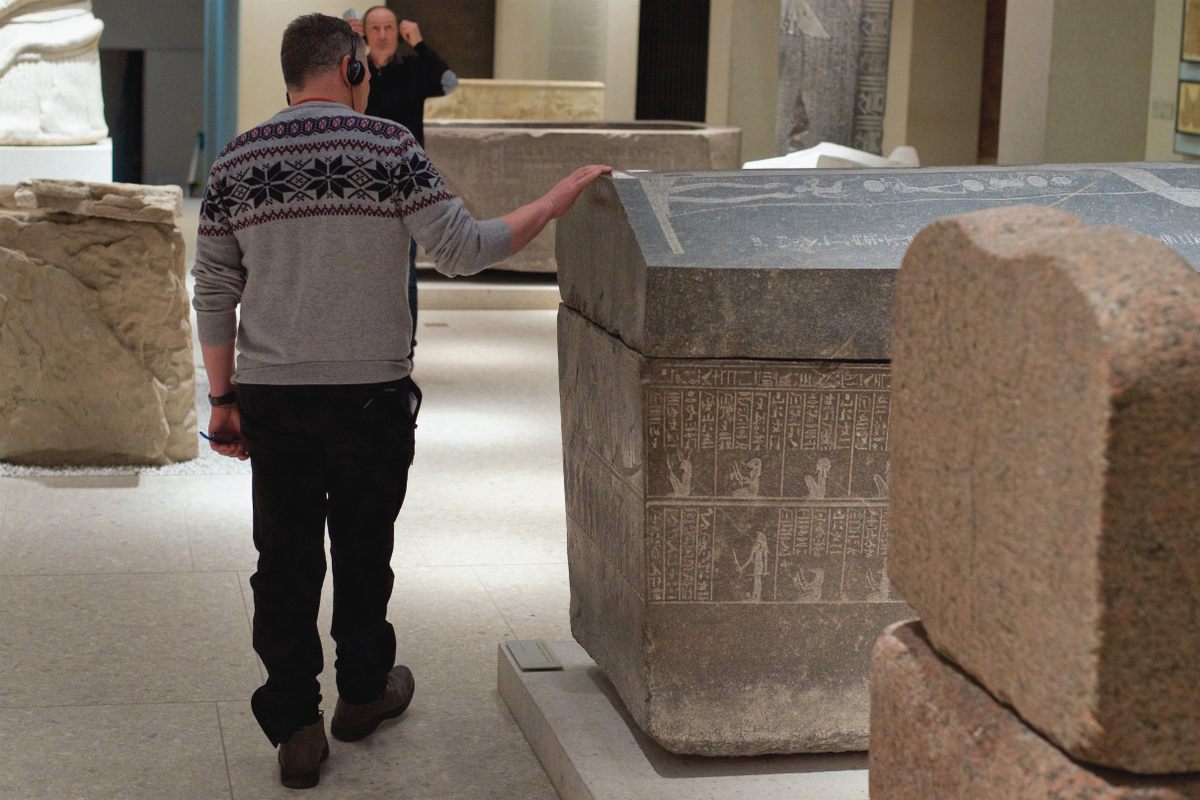

Across 2004 and 2005, Candlin wandered the British Museum, keeping an eye out for what she calls “low-key unauthorized touch.” The results of this study—recently published in The Senses and Society—read like a catalog of small, secret intimacies. (Candlin has also written a book on the subject, called Art, Museums and Touch.) Visitors tap on bowls, lean on plinths, and trace hieroglyphics with their fingers. They pat the head of the Halikarnassos horse, stroke the belly of Septimius Severus, and try to feed sweets to the Dog of Alcibiades. A young boy in the Egyptian sculpture gallery spends some time shadowboxing the disembodied forearm of Amenhotep III, ending the bout with a gentle fist-bump.

Meanwhile, sympathetic but harried attendants bemoan the impossibility of enforcing the gallery rules, which, they say, many visitors aren’t even aware of. “You stop a hundred people touching and there are two hundred more,” one told Candlin. “It’s like trying to turn back the sea.”

Most museum-going is still a primarily visual experience. Exhibits are generally “on view” or “on display,” and visitors learn more about historic and artistic objects from reading programs, plaques, and captions. But over the past few decades, more and more museums have been working to include additional senses: many offer tours for visually impaired people, and some have gotten more experimental, concocting chocolates themed around particular exhibits or creating scratch-and-sniff versions of paintings. But touch, especially, is usually relegated to particular areas, like the Louvre’s Touch Gallery, or the British Museum’s Hands On desks.

This was not always the case, says Candlin. Curiosity cabinets, which arose in Renaissance Europe and are often considered a predecessor to the museum, were meant to be opened; when people visited them, Candlin says, “they would have handled things and talked about them.” As these private collections influenced public institutions—or, as with the British Museum, became them—they intially brought this spirit of openness along. “There are diary entries from the 18th century of people visiting the British Museum and being able to pick up the objects,” Candlin says.

But as museums grew, this became unsustainable. “When you’ve got four million visitors a year, you can hardly have everybody touching something,” says Candlin. People are clumsy, our hands are greasy and dirty, and we love wearing rings and watches that, when applied with force to a delicate object, might as well be bludgeons. As such, although smaller museums still sometimes encourage visitors to interact with their objects, the bigger ones tend to bill themselves as hands-off, except in controlled situations and locations.

And yet, we’re all doing it anyway. A new Tumblr by the photographer Stefan Draschan—selections from which illustrate this article—is full of people poking paintings. Sometimes the transgression goes further, as with the famous Ecce Homo “restoration,” or the crossword puzzle collage, hung in the Neues Museum Nürnberg, that a visitor tried to solve. “If unauthorized touch is factored in… it is clear that many museums are far more multisensory than is generally acknowledged,” Candlin writes.

Ultimately, the question may be why, across centuries and venues, are we so unwilling to keep our hands to ourselves? Candlin’s interviewees had a number of excuses. Some claimed to be doing it to make sure the artifacts were real. Others figured the lack of glass cases in certain of the British Museum’s galleries meant that everything was fair game. At least one guest cited the seeming hardiness of the ancient objects: “The sarcophagus… it’s so solid,” she told Candlin. “It’s made to last.”

But Candlin thinks there’s a larger truth underpinning these pretexts. “I think you can’t really learn about things unless you handle them,” she says. “It makes a difference.” Visitors told her that they wanted to feel how deep an engraving went, or the smoothness of a monument, so as to better understand and appreciate the artistry involved in making it. “I don’t think an IKEA product would be like that after 3,000 years,” one interviewee said of a well-chiseled sarcophagus.

Some people who touched things even went so as to express new empathy for the people doing the work. After touching a carving that didn’t go nearly as deep as it looked, a guest shared with Candlin what they imagined of the laborer’s thoughts: “God, it’s hot here, it’s hard work and all they’ve given me is a bag of rice.”

In this way, touching, Candlin says, is “part of a much bigger, more imaginative encounter with things—trying to somehow make contact with the past.” And there are countless ways of facilitating this type of contact, it seems. Recently, she says, a former head of conservation at the British Museum told her about a visitor who came into the Egyptian sculpture gallery and left tins of cat food as an offering for the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet. “In terms of oddness, that one beats touching,” Candlin says.

Candlin recalls one of her own (authorized) encounters, with a stone hand ax at a British Museum handling desk. “When I picked it up, it sat really nicely [in my hand],” she says. “You had the sense that whoever had made it had a hand like yours. Then the woman at the desk said, ‘You do realize that the person that made that wasn’t even the same kind of human that you are?”

The ax, made tens of thousands of years ago, is one of the oldest things the museum has. “This object, somehow, has passed across this great gulf of time,” Candlin continues. “You’re on one end, this other person is on the other. It’s an imaginative jump, but the object helps you make it.” That’s a powerful way of forming a relationship, and one she has returned to repeatedly during her own museum visits. “I always want to touch things,” she says. “And sometimes I do.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook