The Eventful Afterlife of a Crowd of 19th-Century Skulls

Philadelphia’s famed anatomy showplace, the Mütter Museum, gets a facelift.

In many ways, the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia is, proudly, stuck in amber. “It’s the 19th century in there,” exhibition manager Michael Keys says of the “museum of a museum” where human remains are displayed in glass cases surrounded by gleaming polished wood, much the way they were when the gallery opened after in 1859, after the death of surgeon and medical artifact collector Thomas Dent Mütter.

For visitors, it is a window into the education of medical professionals more than 150 years ago, and it is also an unexpected glimpse of cutting-edge scientific advancements and the debates that still haunt modern medical ethics.

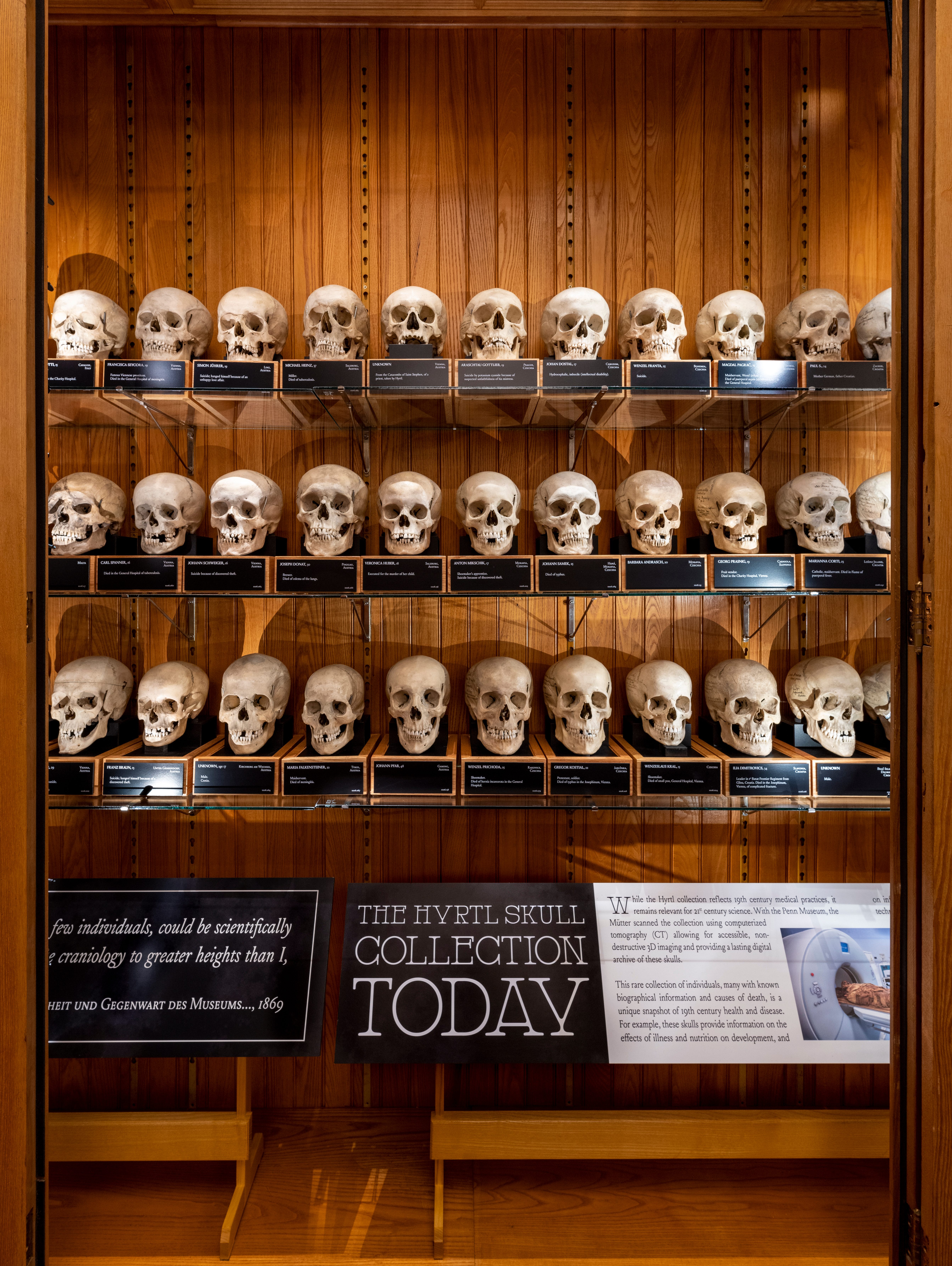

A centerpiece of the museum’s collection—which includes portions of Albert Einstein’s brain—is the Hyrtl Skull Collection, 139 human skulls amassed by Joseph Hyrtl, a Viennese anatomist, in the mid-19th century in an effort to disprove the racist theories of phrenologists who believed cranial shape dictated intelligence and personality. The museum acquired the collection in 1874, and for decades the skulls sat in their original cases on a catwalk overlooking the museum gallery. Through the years, small alterations have been made to the popular display. In the early 2010s, for example the museum replaced skulls’ cast-iron mounts because vibrations from the footfalls of visitors were damaging the bones. And recently, in September 2021, the museum unveiled its latest move—a complete renovation of the exhibit.

“We wanted to create a more contemplative experience,” Keys says. The tall, crowded display cases, which forced visitors to crouch low to the ground or stand on their tiptoes to view every skull, have been reconfigured to put the collection more at eye level. The work gave the museum a chance to assess each skull for conservation needs (one needed some dental work; all needed dusting) and ensure that the environment—light, temperature, humidity—was optimized for their preservation. But most importantly, this revamp offered the opportunity to put the collection in a more nuanced and complete context.

Many of the skulls are inscribed with the individuals’ names and brief medical biographies. Earlier object tags focused on the pathologies they suffered or the causes of their deaths, befitting the museum’s historical focus on physician education. Now the skulls are introduced, first, by name, not condition. The new display also provides more information about the history of the collection—and its future.

As medical knowledge advanced through the mid-20th century, the Mütter collection, and indeed most anatomy collections, fell out of favor as teaching tools, and the primary audience for these artifacts became the general public. Starting in the late 2000s, the same scientific progress that seemed to have rendered the collections obsolete began to open new possibilities for research. In 2007, scientists were able to extract DNA from an intestinal specimen in the Mütter Museum. The individual in question had died of cholera, and the genetic fingerprint of the bacteria that was uncovered has helped scientists trace the mutation of the pathogen.

In 2014, the museum founded the Mütter Research Institute to further explore those scientific opportunities, and to spark conversation about the ethics of such work. “The more we can make these collections accessible, the more we can save lives,” says Anna Dhody, the museum’s curator and the director of the institute. “But is it ethical to do this?”

The majority of human remains housed in museums around the world are from marginalized populations and from individuals who did not consent to donate their bodies to science, Dhody says. In the Mütter Museum’s wider collection are many specimens from poor 19th-century Philadelphians. The Hyrtl Skull Collection is made up of Europeans who were not, by law, given bodily autonomy, such as those who died of suicide, were executed, or died in a workhouse. For Dhody, the responsibility now is to humanize these individuals who were historically mistreated and, if possible, learn from them.

For the Mütter Research Institute, this often means balancing contributing to scientific research and preserving and respecting the human remains in their care. For example, all of the skulls have undergone CT scanning, a series of X-rays that produce cross-sectional images. This has created a large dataset for researchers interested in studying such conditions as concussions or sleep apnea. Digital scans of the skulls have also been used to teach facial reconstruction, a necessary skill for locating missing persons and identifying remains. The Mütter is also currently exploring the possibility of extracting genetic material from a tooth root, without damage to a skull.

Take the skull of Wenzeslaus Kral. Kral died of smallpox in Vienna’s General Hospital more than a century and a half ago, and his skull had been on display at the Mütter Museum for nearly as long. Now, perhaps, the 15-year-old shoemaker can teach modern scientists something important about the spread of the disease that took his life.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook