The Diner That Became a Haven for New York’s Gay Communities

Butchers, drag queens, and Club Kids broke bread together at Florent.

In the 1980s, lower Manhattan’s Meatpacking District began moving from its industrial slaughterhouse roots. The advent of mass refrigeration and affordable transportation now allowed restaurants and markets to order meat from all around the country. Though meat butchers, packers, and distributors still worked in the area, many abattoirs were disappearing.

As the neighborhood transformed, its cobblestoned streets began to see fresh faces. Drowsy butchers weren’t the only people out on Gansevoort Street—the Meatpacking District’s main artery—during the wee morning hours. Partygoers, revelers, and sex workers, many of whom were gay or transgender, joined them.

In light of the horrific AIDS epidemic, gay communities in and around Manhattan found camaraderie wherever they could throughout the 1980s. Drag balls dominated scenes in Harlem. Around Chelsea, the likes of Michael Alig and the Club Kids hosted decadent themed parties. And in the Meatpacking District, members of counterculture communities, as well as people who worked in the area, gathered at Florent Morellet’s eponymously-named diner. Stepping inside Florent’s plastic strip curtains, patrons could often hear tinkling piano, French chansons, and laughter. People sat in snug vinyl banquettes, digging into soupe l’oignon, moules marinières, and tripe.

Morellet, a Frenchman who’d come to New York in the late 1970s, opened Florent in 1985. His new brasserie replaced an old-fashioned diner named the R&L, complete with a wraparound Formica counter and chrome siding. Morellet did little to change those original details. He added framed maps, strung up fairy lights, and tinted the overhead fluorescent lights pink. Despite the physical resemblance to its predecessor, Florent’s menu was far different from the R&L’s, which had mainly been a spot for longshoremen to grab a quick sandwich or coffee. 69 Gansevoort Street became a place to taste traditional French foods and eat a classic American breakfast, with a bevy of people noshing in neighboring booths.

Florent didn’t initially open a restaurant with the intention of becoming “the patron saint of the meatpacking district,” as New York Magazine put it. After unsuccessfully opening a restaurant in Paris, followed by years of managing one in SoHo, Morellet gave the business another shot with Florent. The denizens of late-night Gansevoort began to stream in, and word spread quickly. “I used to go there in between bars, when I was out with my friends, doing drugs and cruising,” longtime regular and renowned fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi said. “Then I’d end up at Florent the next day for a serious lunch meeting and all the same people were there, kind of smiling in secret.” By early 1986, The New York Times had dubbed it “one of the hottest spots in town.”

Florent was never exclusive. From the jump, the locale welcomed everybody: Local butchers, sex workers, drag queens, and clubgoers broke bread together there throughout the night. Even as the restaurant became more popular, Florent and his staff ensured that their regulars were taken care of. He even opened a secret phone line so locals could make reservations.

In 1987, life changed for Morellet: He was diagnosed with HIV. As the disease ravaged gay communities, many friends urged him to stay quiet about his status, thinking it would ruin his business. Instead, he began to put his daily T-cell count on the bottom of his specials menu, a radical act that both fostered openness and created a sense of community for others facing the same diagnosis. He also became deeply invested in other causes, including the “right to die” movement, along with gay rights issues, and organized bus trips to national protests in Washington, D.C.

As a part of the “right to die” movement, Morellet also began passing living wills out to his customers. In an uncertain time of grief and terror, he helped others grapple with it, even when he was dealing with his own fears. Shortly after his diagnosis, he became sick with hepatitis and was told he had two years to live.

31 years later, he’s living in Brooklyn. Over that time, he’s lost many loved ones, including his husband, Daniel Platten, to AIDS. Throughout this time, Morellet remained an activist for others. POZ Magazine, a publication geared towards people living with HIV and AIDS, invited New Yorkers with HIV and AIDS to Florent in 2004. Its 10th anniversary cover featured 100 people, all naked, embracing in the restaurant. Morellet is among the group, with his specials board in view.

Over time, Florent became a sanctuary for those who were different, for transplants, and people who had been cast out by their families. Sean Strub, the editor of POZ and longtime friend of Morellet’s, once told The New York Times about his first visit to Florent. “The restaurant was lit up and … it looked almost like a mirage,” he said. “It felt magical. I remember the tables were very, very close together, so you were sort of seated automatically with strangers. There was a sense of discovery. I was there with three friends. They are all since deceased.”

Florent Morellet wasn’t the only queer pioneer on Gansevoort Street in the 1980s. A droll, curious man named Nelson Sullivan lived nearby, on the corner of 9th Street with his dog, Blackout. Nelson, a expat from South Carolina, knew practically everybody in New York nightlife and devoted his time to recording their lives on his video camera. Throughout the 1980s, he amassed thousands of hours of footage, most of which are available to view on YouTube. His videos include dozens of familiar faces: His closest friend is a young RuPaul. In one video, he visits Keith Haring’s apartment, and in another, he brings homemade prune cake to Michael Alig’s birthday. Before the 1987 Gay Pride Parade, he documented eating dollar slices with Michael Musto.

Aside from being an early vlogger, Nelson became an important chronicler of gay and alternative communities during a turbulent and terrifying time. Many of the subjects of his films, and Nelson himself, didn’t live to see the 1990s. He immortalized people during quiet moments, sometimes eating together at the likes of Florent. In one of Nelson’s videos, we see a 10-minute peek into a night at Florent with Christina Superstar, a frequent subject of his films. (Some may remember Marilyn Manson’s portrayal of her in the 2003 cult film Party Monster). Nelson’s evocative filming style transports viewers directly from a cold, dark Manhattan street into Florent. There, Nelson and Christina order oatmeal, a cheddar omelette, and French fries. The smoke from Christina’s cigarette swirls around the counter. She smiles and laughs, clearly comfortable in this space.

Before coming to New York, Christina lived in Pittsburgh and worked as an English teacher. When she came out as transgender, her family paid her to stay far away. She relocated to Manhattan, where she met Michael Alig and became a part of his Club Kid crew. She became notorious for her fake German accent, flash of bleach blonde hair, and red lipstick. She was often treated poorly by other people in the scene, but Nelson seemed to really care about her. Christina passed away in 1989. That same year, Nelson died of a heart attack.

Ten days after Nelson’s passing, Florent threw a party to lift local spirits. He threw a Bastille Day celebration, in time for the 1989 French bicentennial. He urged partygoers to attend in costume pour la révolution, and he came decked out in full Marie Antoinette garb. The soirée soon ballooned into a yearly street party, and every July 14th, hundreds of revelers squeezed onto Gansevoort.

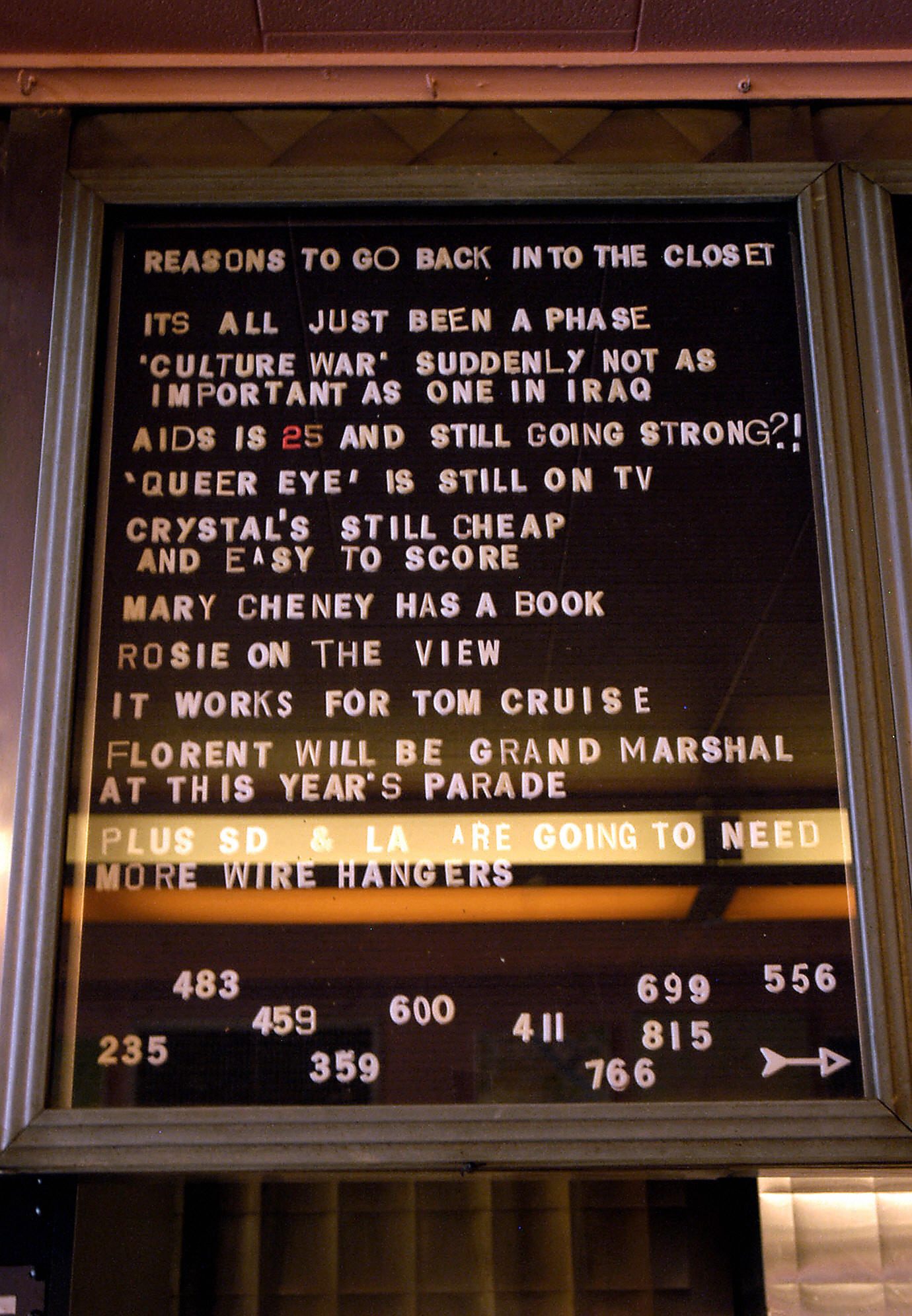

As the years went by, Florent’s following grew, and the restaurant developed different traditions and quirks. The daily specials board began displaying jokes, puns, and witty observations above his ever-present T-cell count. Celebrities including Julianne Moore, Amy Winehouse, Johnny Depp, and Diane Von Furstenberg streamed through on a regular basis, and Sarah Jessica Parker’s character, Carrie Bradshaw, famously dined there on Sex and The City. Throughout it all, Florent never ceased to be a haven for gay communities.

By 2008, the Meatpacking District had completely transformed, with old slaughterhouses becoming expensive boutiques. Faced with increasingly unaffordable rent, Morellet made the difficult decision to close after a brief dispute with his landlord.

As the end of the restaurant loomed, Morellet threw a series of parties themed around the five stages of grief. Each stage was marked with a week-long event that featured performances, a packed restaurant, and plenty of reminiscing. “New York is about change,” Morellet told his patrons during the “Denial” party. “Sometimes it’s good in life to be kicked out,” as he said in the 2008 documentary Florent: Queen of The Meat Market. “… A better word is ‘I’m being kicked forward.’” It’s a touching sentiment coming from somebody who created a home for so many people who had lost their own.

Since closing his restaurant, Morellet has urged his loyal customers to not cling to the “terrible disease known as nostalgia.” He doesn’t have plans to open a new restaurant, and is happy to let Florent remain a beloved memory. Now, he’s focusing on other passions, including his work in activism, artwork, and cartography.

Florent officially closed over Pride weekend in 2008. Longtime locals and artists performed, gave speeches, and sang the praises of a man who fostered communities during a time when people struggled to survive. There, he was presented with a cake (fittingly decorated as Marie Antoinette), which he cut and served through laughter and tears.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook