A Century Ago, 3 People Met Their Deaths Gawking at the Frozen Niagara Falls

Stay off the ice bridge.

When the temperature plummets around Niagara Falls, the landscape looks like a dreamy scene from The Nutcracker come to life: Everything is white and sparkly, with the spray bedazzling lampposts and viewfinders with a crystalline crust. Though the Falls rarely freeze completely, it’s not uncommon, on frigid days, for the vista to look something like a tundra, with ice frozen dozens of feet thick. Anyone willing to risk wind-slapped cheeks can venture out and gaze at the wonderland—and this past weekend, when Fahrenheit temperatures slipped into the single digits, some onlookers did, photographing white expanses and long, sharp icicles.

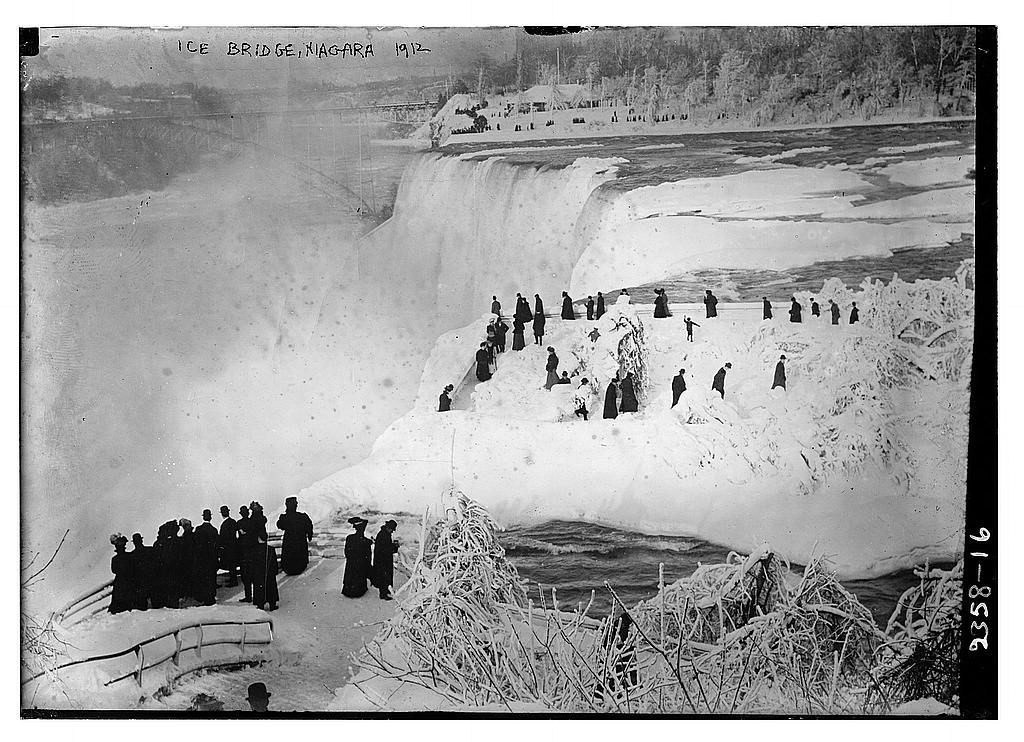

These visitors mostly gawked from shore—but a century ago, people often clambered out onto the ice itself. When chunks of ice from Lake Erie or the upper Niagara River dropped down into the falls and the basin below, they formed an “ice bridge” long and wide enough for visitors to cross from Canada to the U.S. and back again. And they did just that, sometimes stopping along the way to visit souvenir stands or warm up with a boozy drink.

Scores of people turned out on Sunday, February 4, 1912, crowding onto a piece of ice roughly 1,000 feet long, a quarter-mile wide, and up to 80 feet thick. A little after noon, there was a loud crack, “like the roaring of a park of artillery,” and the ice broke loose. “The great ice bridge in the gorge just below the mighty cataract moved suddenly out with its freight of human beings,” the Buffalo Evening News reported.

Some people rushed toward land, but slipped into the water. They were yanked ashore on the Canadian side, shivering, with their clothes plastered to their bodies. An unfortunate trio—a teenage boy named Burrell Heacock (or Hecock), and a young married couple, Eldridge and Clara Stanton—remained stuck on the ice, which was “carried down stream at frightful speed… grinding and crushing about them,” the Evening News wrote.

Fire crews hurried to toss them coils of rope, but with hands pricked and numbed by the cold, the trio fumbled while trying to fasten the lines to their waists. The couple “sank to their knees, and the waves washed over them, and then they disappeared in the seething, grinding mass of ice and water,” a Pennsylvania paper recounted. The three plunged to their deaths in plain view of the crowd above. “Gigantic Freak of Nature Breaks, Taking Man, Boy and Woman,” read a San Francisco headline the next day.

Prior to the tragedy, “the bridge was considered to be absolutely safe,” the Buffalo Commercial reported. These weren’t the first lives to be lost on the ice, but the tragedy is said to have ended the practice of ambling out on the bridge. Ever after, visitors were instructed that the drifts and glittering formations are best viewed from a distance, and on solid ground.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook