The Renaissance Knives That Will Have You Singing for Your Supper

Sweeney Todd would approve.

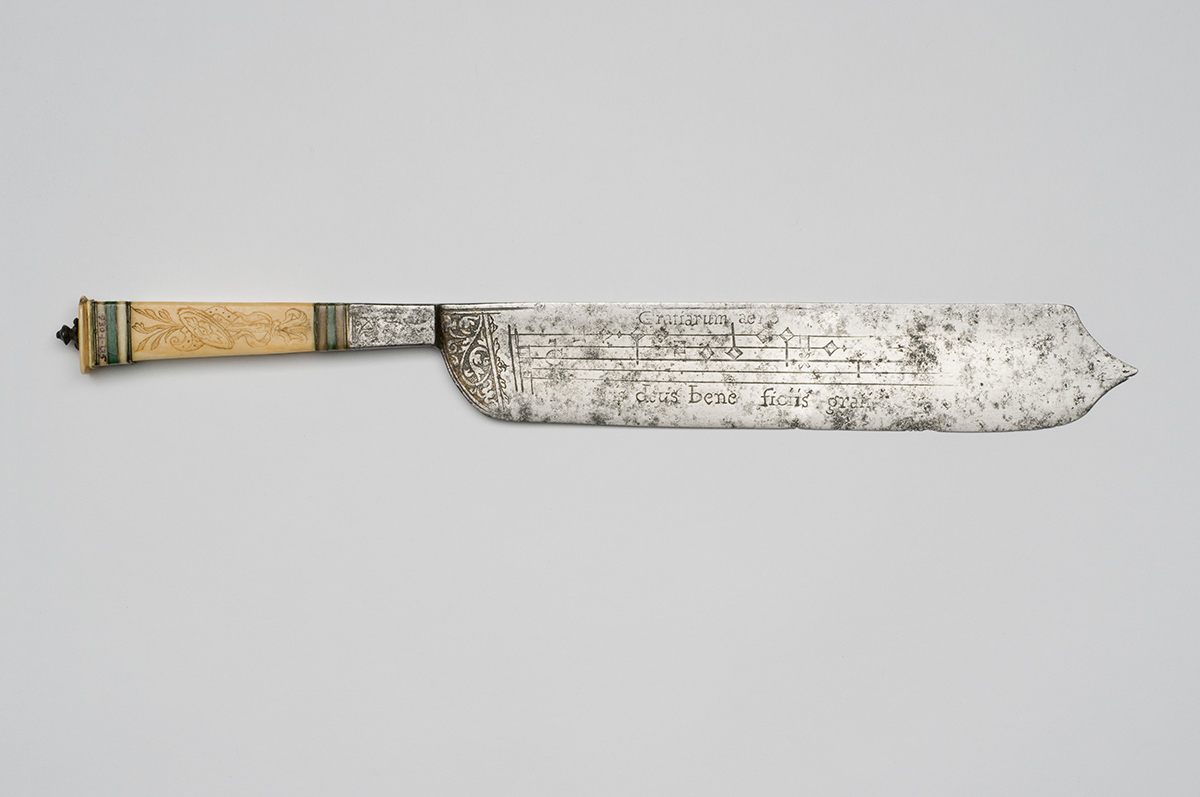

Outside of a Disney movie, it’s hard to imagine chefs at their carving stations wiping the jus from their blades and bursting into song. But that’s just what “notation knives” seem designed for. These rare knives—only sixteen are extant—are perplexing in both their design and their use. Who was carving meat with these blades, and are they the same people who were singing the music etched onto their blades?

The blades, which date from the early to mid-16th century, all seem to have been made somewhere in France, but for an unknown Italian client. Italian knives of the period typically bore a coat of arms or emblem that would be upright when the knife was held point up; in other countries, one viewed the emblem holding the knife horizontally.

Transcribing the notation reveals that all the knives we know of come from just two separate sets. They don’t seem to represent a lost Renaissance tradition of singing meat carvers so much as the peculiar needs of a singular institution. Today, the knives are scattered across collections in France, England, the Netherlands, and Philadelphia.

The craftsmanship and materials are superb; many have exquisitely decorated ivory handles. Their unusual shape—a broad, flat blade with a pointed tip—is the first mystery. The point evokes a smenbratori, or carving knife (carvers jammed the tip into a joint of a roast and twisted to break it open). But to a bladesmith like Josh Davis, who recreated one of the knives from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, it doesn’t seem designed with serious cutting in mind. “It isn’t really supposed to be well-balanced,” he says. “I think it was more of a serving knife.” A knife that’s really more of a spatula, in other words, with a broad, flat blade that also provides a convenient surface for the music.

The blades do show signs of wear, even if we don’t know the context of their cutting and stabbing. Their owners certainly weren’t acting like Sweeney Todd, butchering neighbors into meat pies and then singing about it, as in the Stephen Sondheim musical. The texts on the notation knives are much more genteel. One side of the blade bears a Latin Benedictus, or blessing, to be sung before a meal (“May the three-in-one bless what we are about to eat”); and on the other side, a Grace, for afterward (“We give thanks to you, God, for your generosity”). The wording is the same on both sets of knives, and is not a phrasing known elsewhere, which again suggests the requests of a unique client.

Of the two sets, one seems to be for four singers, the other for six. (Some of the knives are duplicates, so there aren’t 16 different lines of music.) In the latter case, one knife is labeled “Superius II,” implying the existence of a missing “Superius I.” The music itself is typical of its period, albeit necessarily brief. Recordings made for The Victoria and Albert Museum last a very pleasant 30 seconds.

It’s likely that the knives’ original use was more ritual than practical. “What makes sense is some sort of social gathering that regularly takes place that has that sort of formal element to it,” says Dr. Flora Dennis of the University of Sussex, who’s done extensive research on the knives and coordinated the V&A recording. “It could be a court, it could be a confraternity [a lay religious or charitable society], or it could be something like an academy [a more secular, formalized intellectual or artistic group].”

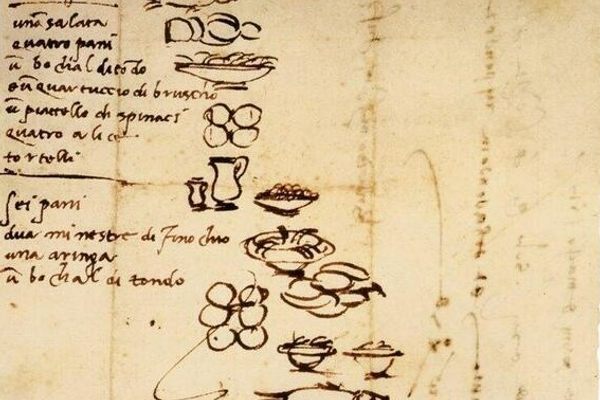

The Renaissance in Italy brought a renewed belief in the value of individual human life on earth; the divine wasn’t forgotten, clearly, but striving to make life better for oneself and one’s community became worthwhile, celebrated goals. Confraternities and academies gathered with the intention of improving themselves and the world around them, either through charitable or artistic acts.

In that context, it’s intriguing to see the practicality of a utensil being combined with an appreciation of higher aspirations. These knives, beautiful objects that combine the earthly need to eat, the heavenly art of music, and a salute to the divine, represent the values of the Renaissance very well in that regard.

Dr. Dennis says the knives are very much of their time. Prior to 1500 or so, individual singer’s parts would not have been written separately. All the parts would be written in one book, like a modern score, with singers’ parts clustered around it (which in this case would call for a large sword, at the very least). By the end of the century, books with separate parts, one to a singer, had become the norm, a development hastened by the advent of Printing.

Musical notes made the leap from page to artwork around the same time, both in terms of genuine music, as on the knives, and fanciful decoration that denotes music generally: Think of every comic strip bird you’ve ever seen, tweeting away.

Long unknown, the knives became de riguer in French private collections in the 19th century, part of a wave of Italian objets d’art that made their way to France in the wake of Napoleon’s conquests. The examples at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for example, came from the collection of Edmond Foulc, a renowned Parisian collector.

The knives have all the attributes collectors of that era loved: They are superbly-crafted from exotic materials, rare, and confounding in their purpose. Today the Museum displays the knives as Foulc would have, mixed in with other objects, some scientific, some artistic, some natural—a Cabinet of Curiosities.

In that context, they were meant to inspire conversation and discussion, rather than song. Foulc could show the knives to his admiring guests, prompting a speculative, even philosophical conversation about their intended use and meaning. The knives inspire the same questions today; they’re curiosities, items to wonder about in a Cabinet of Wonders.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook