Meet the Cryptids Haunting Ohio’s Imagination

A new exhibition pays homage to some of the Buckeye State’s beloved—and infamous—legends.

One evening in August 2016, Sam Jacobs and his girlfriend were playing Pokemon Go near the inky shore of Lake Isabella, in Loveland, Ohio. The lake is regularly stocked with catfish, bluegill, trout, and perch (to the delight of local fishers). But the couple saw something that struck them as more than a little odd—and it wasn’t a creature roaming their phone screens.

“We saw a huge frog near the water,” Jacobs told Cincinnati’s WCPO television station. “Not in the game,” he added. “This was an actual giant frog.”

Jacobs paused his play and snapped some grainy photos. They’re tricky to decipher, but appear to show a dark figure standing in the gently rippling water, light bouncing off its enormous, saucer-shaped eyes. Jacobs was convinced he was seeing a frog rearing up on its hind legs.

“I realize this sounds crazy,” he told WCPO. “But I swear on my grandmother’s grave this is the truth: The frog stood about four feet tall.”

Jacobs wasn’t the first person to claim to see a monstrous amphibian roving Loveland. In 1972, a local police officer named Ray Shockey said he crossed paths with an enormous frog near the Little Miami River. Shockey kept it pretty quiet, Dayton’s Journal Herald newspaper reported that year; he didn’t want to spook anyone.

Soon after, however, his partner, Mark Matthews, was scouting the same spot when he encountered a creature that fit Shockey’s puzzling description. It hopped toward him, he told the Journal Herald—and while it wasn’t aggressive, exactly, it was unusually, almost unbelievably, large. Keen to get a closer look and preserve the evidence, he landed four shots with his .357 magnum. He told the Journal Herald that he suspected the thing was a hefty iguana that had lost its tail—but that it was hard to say for sure, the paper noted, because “the animal gave one last hop, fell into the river and was washed away.”

There’s no reason to suspect that Rutherford B. Hayes, America’s bookish and extravagantly bearded 19th president, ever laid eyes on the giant, bipedal Loveland Frog (or Frogman), as it’s come to be known. Or that he was scared by an unsettlingly oversized iguana. He probably never made the acquaintance of the Mothman either. Or the Grassman (Ohio’s answer to Bigfoot). Or South Bay Bessie, the Loch Ness–style monster said to patrol the waters of Lake Erie.

But Hayes’s presidential library and museum, in Fremont, Ohio, has recently mounted a show called “Ohio: An Unnatural History,” about the legendary creatures that go bump in the Midwestern night.

The museum, which normally traffics in tangible objects and measurable facts, doesn’t view its dalliance with the paranormal as anything unusual. “Not only do we cover presidential history, but also local history,” says Kevin Moore, associate curator of artifacts. “And we view local folklore as part of Ohio’s local history.”

Hayes had a personal library of thousands of books, Moore says, and was a history buff to boot, with an interest in the legends of local Native American cultures. “We want to appreciate the folklore just being part of Ohio culture—not get into any effort to validate or disprove it,” Moore says.

Tall tales, however dubious, don’t spring from nothing—and that makes folklore a useful window into local history, says Esther Clinton, a folklorist at Bowling Green State University, in a video accompanying the exhibition.

“The stories that become folklore are the stories that are repeated often, and not just by the same person,” Clinton says in the video. “What that means is that these are stories that make emotional and intellectual sense to people. If we look at folklore, that tells us a lot about what are people thinking about, what are they worried about?”

To bring the creatures in the exhibit to life, the library tapped Dan Chudzinski, a historian, special-effects artist, and animal-anatomy aficionado who doubles as the curator of the Mazza Museum at the University of Findlay.

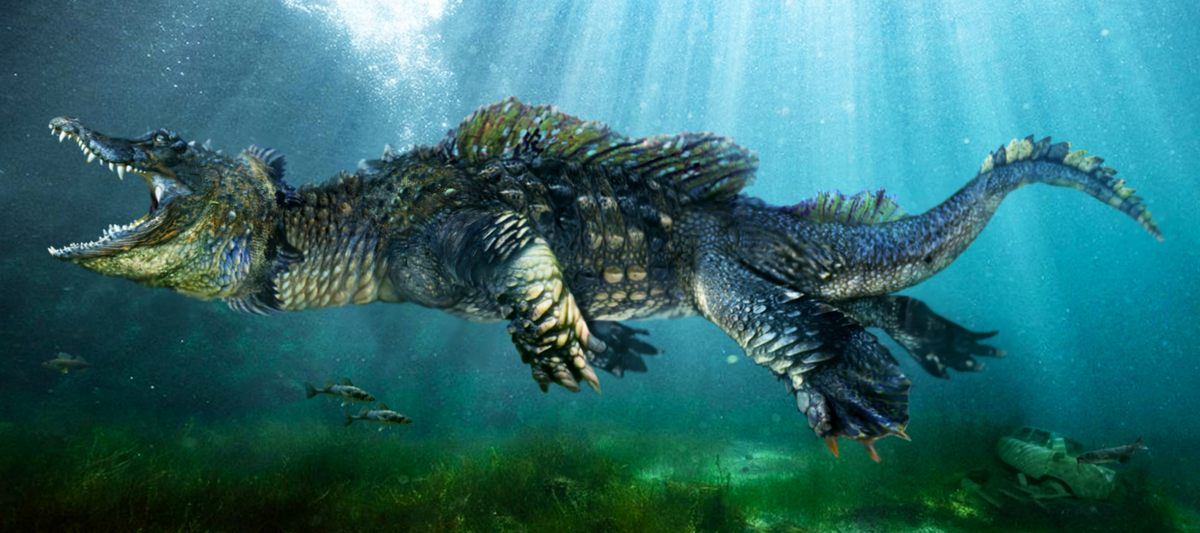

The child of an anatomist-cum-biology-professor, Chudzinski has always been drawn to both known anatomy and the creatures that wander the foggy, gray margins of our imagination. He cut his teeth on taxidermy as a teen, and volunteered at the Toledo Zoo. At the Mazza Museum, which is rich in children’s book illustrations, he strung a 40-foot-long sculpture of Bessie, made from urethane foam and custom hardware, from the ceiling. It has a massive skull, studded with 200 teeth, and is roughly the size of a bus—a fact that Chudzinski uses to playfully taunt schoolkids, saying, “If you all fit into one bus, theoretically you could all fit into one really hungry lake monster.”

Though he often creates sculptures so uncannily lifelike that you expect to see the eyes blink or the chest rise and fall, Chudzinski’s work for the cryptid show mainly consists of 2D images. He wanted them to feel as informed and convincing as paranormal portraits can possibly be—thoughtful and unique, yet recognizable, sporting the iconic characteristics.

To research one of his subjects—the Headless Motorcyclist, said to roam the roads after a gruesome accident—Chudzinski visited local libraries to look for reports of a vehicular decapitation. He also interviewed people who claimed to have encountered the various creatures he portrayed—and did a little fieldwork of his own.

For Grassman inspiration, he visited creatures including Kwisha, a silverback western lowland gorilla who lives at the Toledo Zoo; artist and ape have known each other for about 18 years. To compile characteristics for the Loveland Frog, Chudzinski tromped to the pond near his house, where he observed the pickerel frog’s speckled skin and the tree frog’s ability to conceal itself up in the canopy. (He figured it would be superlatively creepy if the Loveland Frog could scale trees and conceal itself while spying on the humans below.)

To capture the moods he wanted to convey in the background, Chudzinski says he went “to locations that people wouldn’t wander around at times when people definitely wouldn’t go out.” There, he asked himself: “What sounds do I hear? How am I feeling?” To up the eeriness even further, he depicted most of the creatures at dawn or dusk, surrounded by wisps of fog.

Some of the legends, like the Loveland Frog, have local or regional roots. Stories of the Mothman have flitted around West Virginia as well as Ohio. (The two states were linked by the Silver Bridge until 1967, when it collapsed, resulting in dozens of deaths.) The Pukwudgies—little troll-like creatures spiked with quills—are hallmarks of Wampanoag and Algonquian stories, Chudzinski says. Others are Midwestern twists on other, established creatures. The Grassman, Moore says, is clearly a relative of Bigfoot or Sasquatch (though the Ohio version is said to be surlier than its Pacific Northwest counterpart).

Many have spawned local traditions or swag. The Loveland Frog earned its own musical (Hot Damn! It’s the Loveland Frog), and the Great Lakes Brewing Company sells a beer called the Lake Erie Monster, a seasonal Imperial IPA it markets with a logo of a menacing, wave-riding serpent.

These creatives are elusive, and the stories about them have an element of shapeshifting too. The legend of the Loveland Frog may actually be a mangling of the telling of an extraterrestrial encounter, said to have occurred in the 1950s, according to the exhibit.

The Mothman story has changed too. In November 1966, the Associated Press reported alleged sightings of the Mothman in Point Pleasant, West Virginia, just across the bridge from Gallipolis, Ohio, and described the creature as a “gray and white ‘thing’” that looked like a “man with a 10-foot wingspan who flies after cars at 100 miles per hour.” The AP noted that the creature was winged, but didn’t mention anything about the searingly red eyes that would figure into later accounts.

Even as cryptids evolve in the popular imagination, the people who helped stoke their stories sometimes wind up recanting. After Sam Jacobs claimed to see the Loveland Frog in August 2016, Mark Matthews—the gun-slinging patrolman from 1972—got in touch with WCPO to call bull on the whole thing. He hadn’t seen a creature standing on its hind legs, he clarified—it had scuttled under a guardrail. And the body wasn’t lost to the river—he had put it in his trunk, certain that it was just a very large iguana. “It’s a big hoax,” he said.

The new exhibition doesn’t adjudicate the tales it tells. But it does make a curiously compelling case that murky accounts belong in the annals of history, shoulder to shoulder with real-world artifacts. They all help us understand the stories a place shares about itself.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook