Why We Call Winter Storms ‘Weather Bombs’

The “bomb cyclone” is a linguistic specter from the 1940s that’s gaining power in 2018.

In the first week of 2018, two types of bombs made the American news—the nuclear kind, thanks to exchanges between U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un, and the weather kind, thanks to a storm threatening America’s East Coast. The “bomb cyclone,” which was unresponsive to diplomacy, was the more immediate (if less existential) threat.

In recent years, it seems that the words used to describe weather have become more histrionic. When the Moon is closest to Earth, we now call it a Supermoon, instead of a “perigee syzygy.” A fierce storm that’s not quite a hurricane is now a Superstorm. And a storm characterized by “explosive cyclogenesis” is now a Bomb Cyclone.

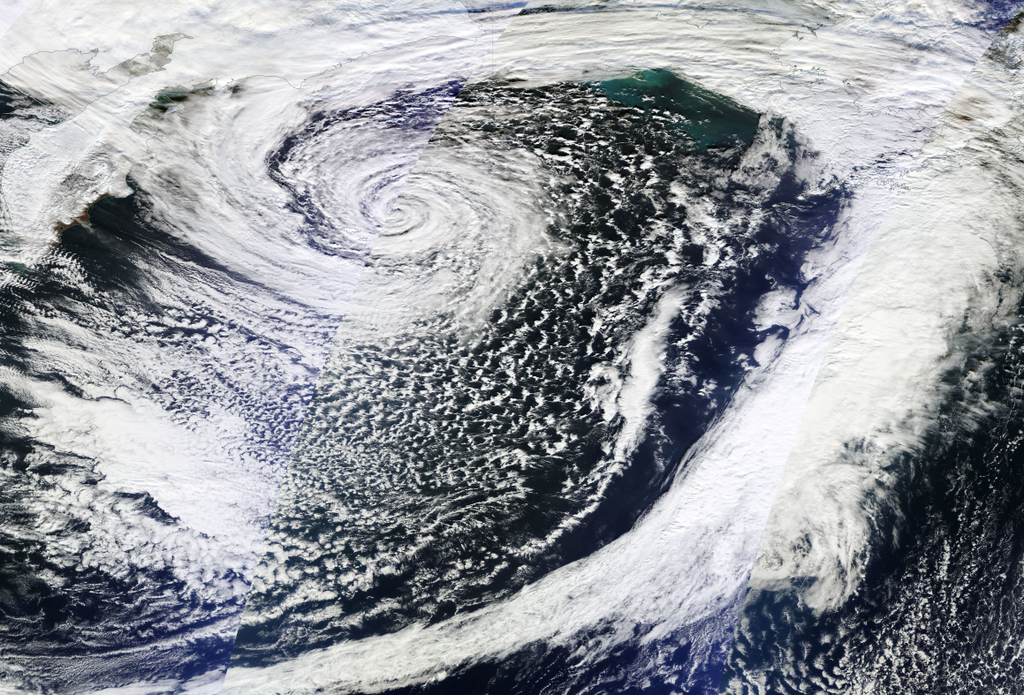

Actually, there are many incendiary names for these types of storms—bombogenesis, weather bomb, sea bomb. The term “weather bomb” was first added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015, as a sub-entry. Unlike some other dramatic weather words, a weather bomb has been given a technical definition. Its modern usage starts with a paper published in 1980, in Monthly Weather Review, on the “Synoptic Dynamic Climatology of the ‘Bomb.’” In that paper, two MIT meteorologists defined a “bomb” as a storm where the central pressure falls dramatically in less than 24 hours. They were interested in this phenomenon, they wrote, because of its “great practical importance to shipping and coastal regions.”

The origin of the term, though, went back further, one of the paper’s authors later told USATODAY, to the 1940s and Norway’s Bergen School of Meteorology. Back then, a sea “bomb” didn’t have a formal definition, but the meteorologists used it to refer to destructive sea storms. At that time, the threat to ships, crucial to creating strategic advantage in World War II, was usually manmade bombs; it’s easy to imagine how the metaphor of a “sea bomb” would have jumped to mind.

Although the attention to the looming bomb cyclone would indicate otherwise, these storms, though dangerous, are not so uncommon. They come on fast and leave destruction in their wake, but they’ve rarely whipped up such explosive anxiety before. (Consider, for instance, this relatively calm report about the bomb cyclone of 2014.) But human beings have long read omens in the weather, and when people have bombs on the mind, violent storms take on an air of added significance and threat, whether in the 1940s or late 2010s. The bomb that’s approaching the East Coast is a threat, for sure, but the way we talk about it makes it that much more frightening.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook