The Underground Magazine That Sparked the Longest Obscenity Trial in British History

In 1970, the editors of OZ magazine handed over the reins to a group of teens. Not long after, the police showed up.

At a New Year’s Eve Party in 1969, the Australian journalist Richard Neville turned to his OZ magazine co-editor Jim Anderson and worried aloud that he was becoming old and boring. It must have seemed utterly inconsequential at the time.

Less than six weeks later, however, in the February 1970 edition of the magazine, the editors placed a classified advertisement in its back pages. “Some of us at OZ are feeling old and boring,” it began, “so we invite any of our readers who are under eighteen to come and edit the April issue.” Applications could be individual or group, and chosen participants would not be paid. Instead, the editors wrote, “You will enjoy almost complete editorial freedom. OZ staff will assist in purely an administrative capacity.”

Just over a year later, the resulting issue of OZ would spark the longest obscenity trial in Britain’s history, and a landmark case in the history of counterculture. Over the space of a few months, hundreds of letters were sent to British newspapers arguing over the case, and inches upon inches of column space taken up by hand-wringing commentators. Seething resentment between two generations had come to a head. The OZ trial became the emblem of this cultural clash.

OZ magazine began in Sydney, Australia, with Neville. There, he and his co-editors were charged twice for printing an obscene publication. In September 1966, he came to London without plans to resurrect it. But, he said in Jonathon Green’s oral history, Days in the Life: Voices From the English Underground, “I sensed there was a substratum of genuine irritation with the society. There was no access to rock ’n’ roll, pirate radio had gone, women couldn’t get abortions.” Most of all, he noted the lack of an underground press: “This again was something which seemed like another piece of repressive puritanical behavior that one wanted to fight.”

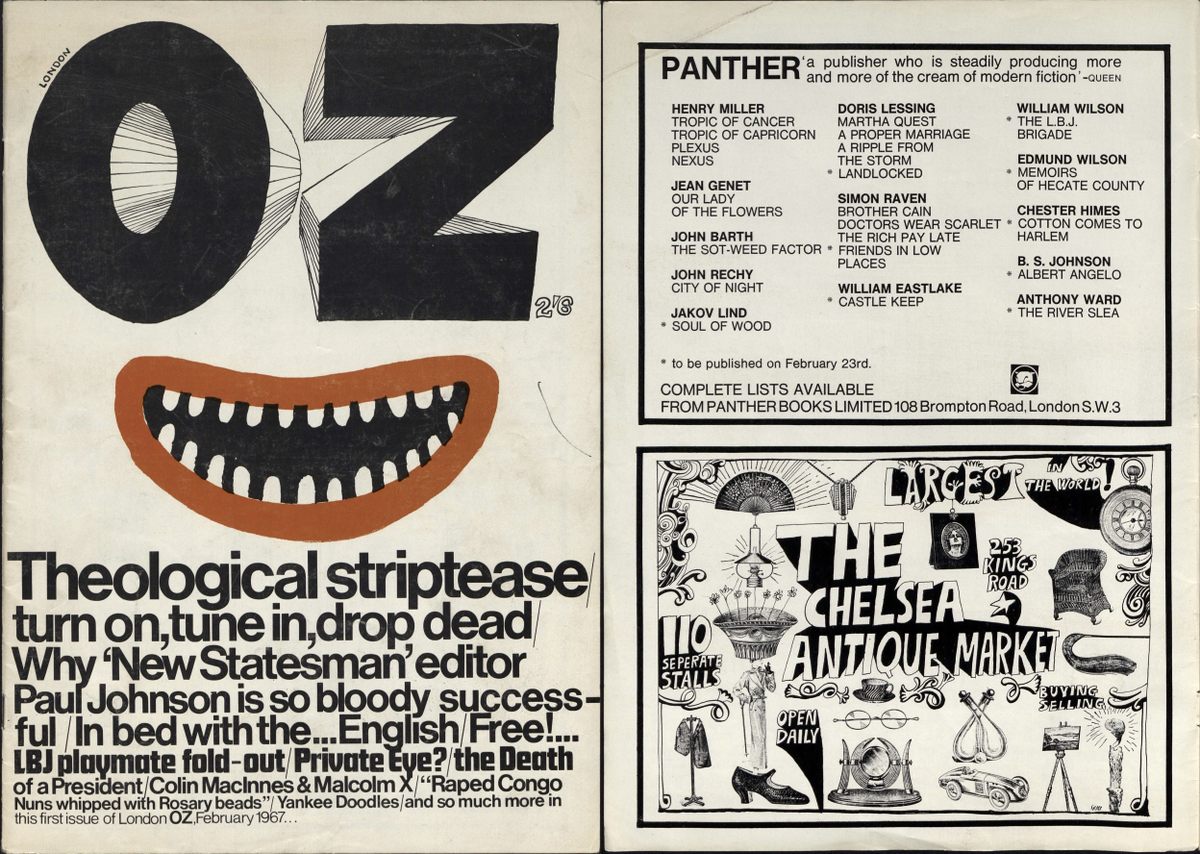

Whether as an answer to this or a rallying call against society, the first issue of British OZ was published in January 1967. Its 24 pages included an obituary for “the novel,” a feature on why there were so many penises in American pornography, and a comic strip entitled The Somewhat Incredible Turning On of Mervyn Lymp, Bank Clerk Extraordinaire. (At that time, “turning on” meant opening up your mind, usually—though not necessarily—through taking drugs.)

OZ was satirical, irreverent, and psychedelic. Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t very lucrative. Speaking to Green in 1986, Anderson remembered paying their many contributors nothing, or whatever they could afford. Issues sold perhaps 30,000 copies apiece. (Readership, however, was much larger–it was the kind of rag you might pass around to your friends once you were done with it.) From an aesthetic perspective, it was scrubby and anarchic—the designers, he said, had been “set loose on an IBM typesetter with several trips of LSD inside them.” Inside, there were ribald jokes and cartoons, gig listings and calls to readers to “TAKE THE PLUNGE! Commit a revolutionary act. Subscribe to OZ.”

By the time 1970 rolled around, there were three men at the paper’s center—Neville, in his late twenties; Anderson, in his early 30s; and Felix Dennis, who turned 23 that year.

Neville was the paper’s engine. Impossibly charming, he inspired cultish devotion in those around him. “No one else would ever have managed to get me working for nothing,” said Dennis, who would go on to be a publishing magnate worth over a billion dollars. “He used to charm birds off trees.” Sandy-haired Anderson, who had trained as a lawyer in Australia, saw himself as a satirist. He was camp, ironic, and openly gay at a time when it was dangerous, even illegal, to do so. Whiz kid Dennis was a failed musician who had caught the group’s attention when he submitted a home-recorded tape to the magazine explaining what was wrong with it. Now, he was responsible for their finances, advertising, and distribution.

A memorable crew of movers and shakers buzzed around Neville and the magazine, among them the feminist writer Germaine Greer, the illustrator and artist Martin Sharp, and the artist and political activist Caroline Coon. “[Neville’s] idea of a good time was going round getting fantastic people to write for the magazine,” Dennis told Green in 1986. “That was his talent. He lived on his wits.” Between the celebrity endorsements, the off-the-wall content, and a genuinely explosive anti-establishment streak, the magazine grew popular with “countercultural” teenagers and young adults.

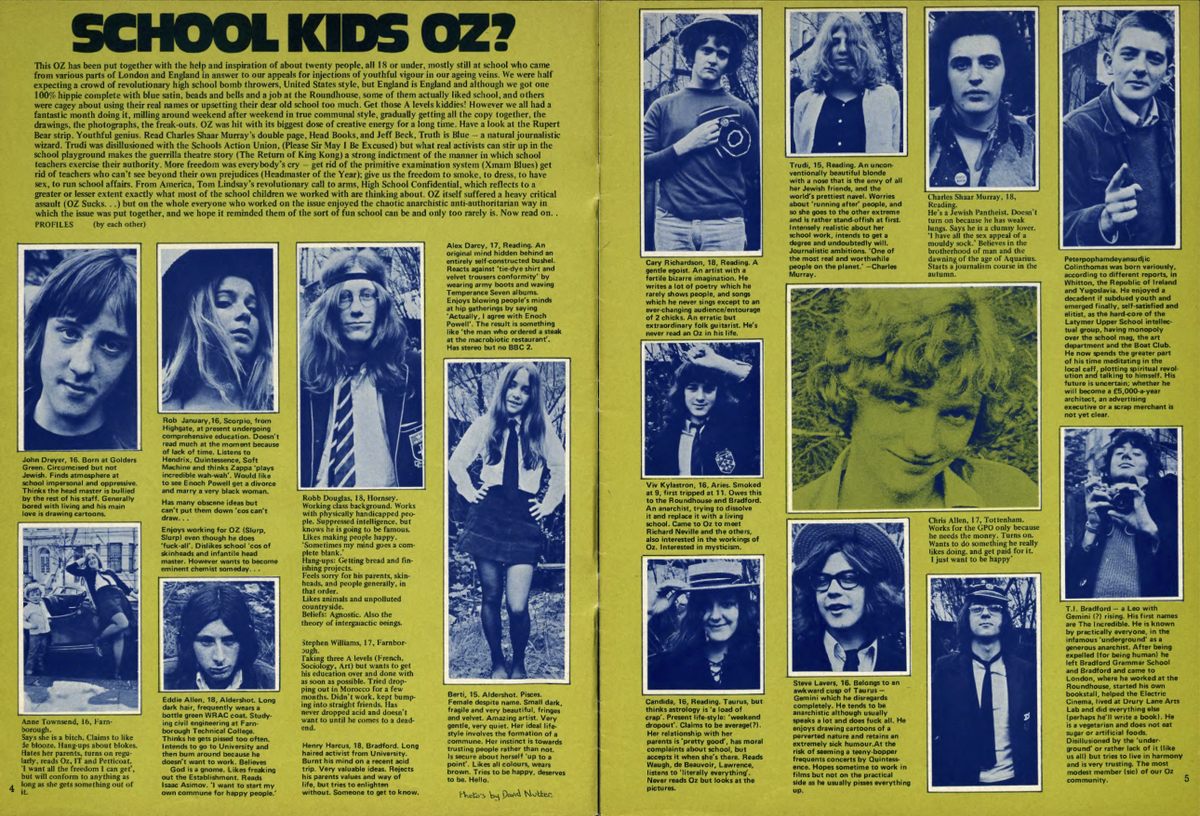

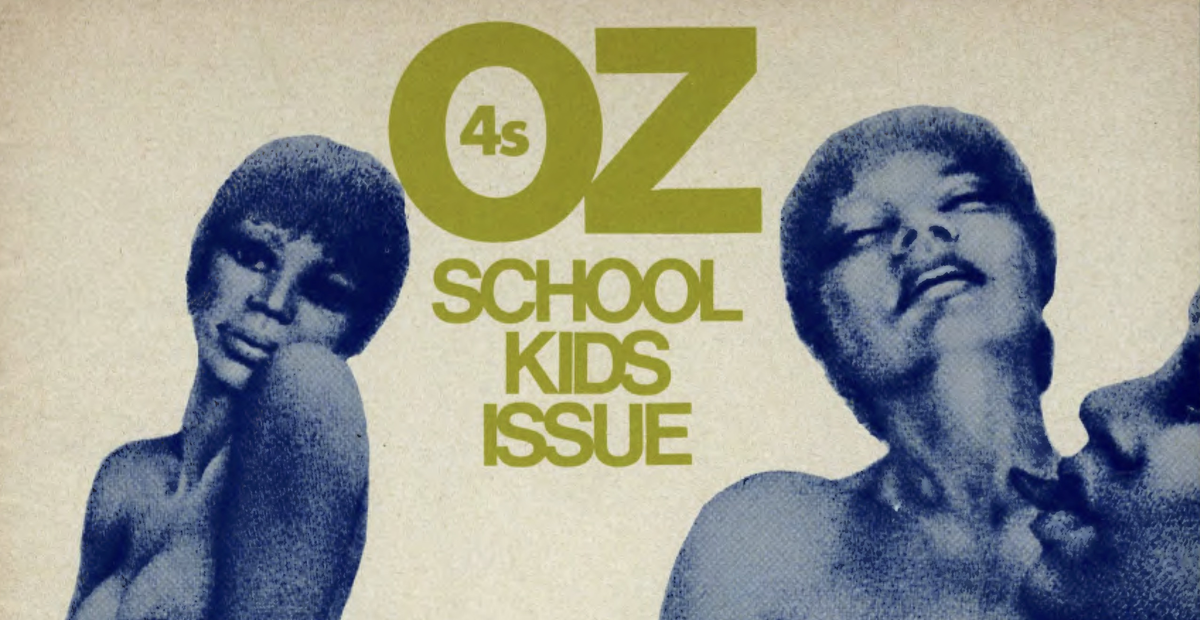

All of this led to the most infamous issue of OZ: number 28, the Schoolkids issue. Dozens of teenagers had seen the advertisement in the back pages of OZ 26. In early 1970, a little over 20 chosen favorites crowded into the magazine’s headquarters: a basement flat in Notting Hill Gate, London, with a lingering scent of marijuana, incense, vegetarian food, and laundry. (In the decades since, some of these young volunteers have gone on to considerable success: the journalists Peter Popham and Deyan Sudjic; photographer Colin Thomas; and Harper’s editor Trudi Braun.)

In a 2001 article for The Guardian, Charles Shaar Murray, now a music writer, remembered the basement as “dimly lit and exotically furnished.” In that room, the “glitterati of the metropolitan underground” mingled with teenagers from across the United Kingdom and handed them the reins to the magazine. “All three were at least as interested in us as we were in them,” Shaar Murray wrote. “As actual (rather than notional) kids, we were interrogated for our opinions on education, politics and society as well as on sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. Given access to the magazine, what would we want to say?”

Over the course of the following weekends, these teenagers put their heads together to answer that question. The result was literally puerile. Obscene, and thoroughly intended to be, the cover boasts blue, pneumatic breasts, while on page 10 a lewd cartoon of a masturbating teacher reaches for a teenage boy’s bottom. Phalluses proliferate. A rambling opinion piece talks about the various ages at which girls in a contributor’s school had lost their virginity. The final result, aesthetically and otherwise, is somewhere between Ronald Searle’s Molesworth, Rabelais, and The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine film.

Eventually it went out onto stands, didn’t sell all that well, Shaar Murray recalled, and seemed to have been quickly forgotten.

Two months later, the Obscene Publications Squad raided the basement flat. The doors were locked, the phones disconnected, and 400-odd issues of OZ 28 carted away as evidence. There were a number of reasons for police interest in the magazine. One was a general disdain for, and fear of, the underground press. Another was the ongoing clash of cultures between the old guard and a rising tide of dope-smoking, free-loving hippies. The other was more technical, Anderson told Green. Police harassment of “underground” printers had forced them to go to increasingly hardcore presses, which usually printed highly illegal pornography. OZ wasn’t exactly pornographic, but did have a preoccupation with “sexual freedom and sexual liberation,” Anderson said. “If we wanted to publish a picture with sexual content it would also have a point to make, and we would insist on publishing it.” Connections with these pornographic printers didn’t help the magazine’s legal situation.

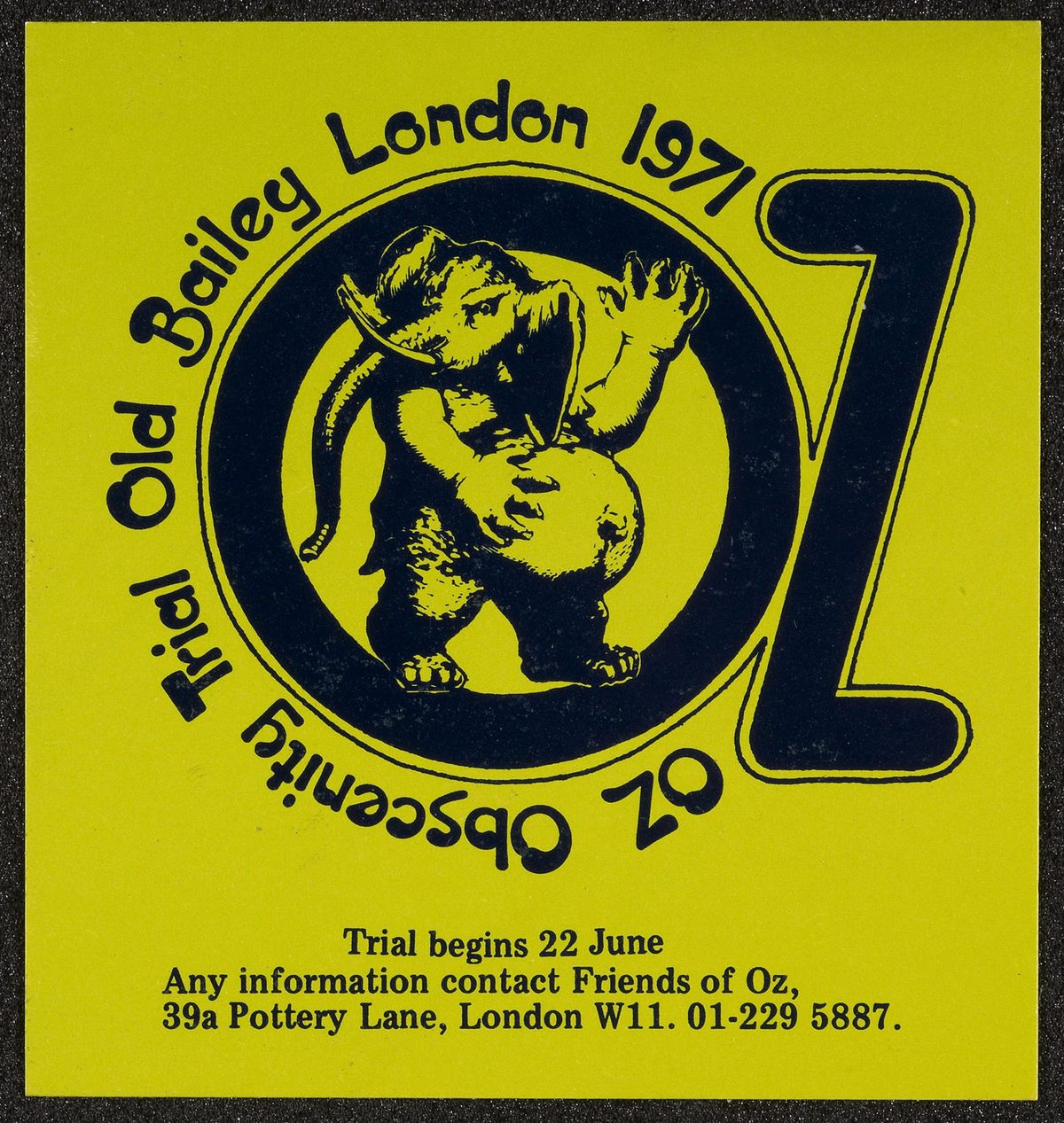

And so, in late June 1971, Neville, Anderson, and Dennis found themselves in court number two of the Old Bailey. They faced numerous charges, among them charges of “conspiring with certain other young persons to produce a magazine containing obscene, lewd, indecent and sexually perverted articles, cartoons, drawings with intent to debauch and corrupt the morals of children and other young persons and to arouse and implant in their minds lustful and perverted desires;” publishing the issue; sending it out through the post; and possessing 474 copies of it for publication for gain.

Police, Dennis told Green, seemed to have entirely misunderstood the premise of the issue—rather than being for school children, it was by them. “They understood it towards the end, just about, but they didn’t believe that children could have produced it,” he told Green. “They actually truly believed that we’d got a bunch of children and that we pretended they’d written it but that really we’d written it.”

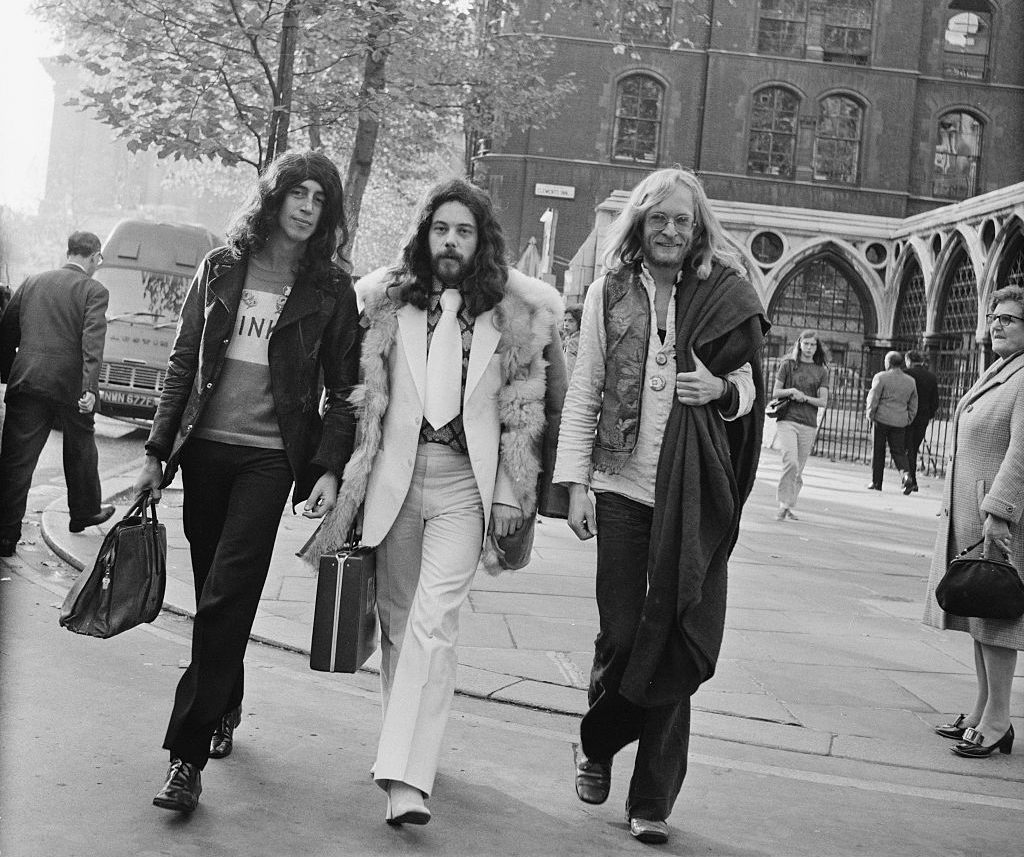

What followed was six weeks of legal squabbling, costing the British public some £100,000—well over a million pounds in today’s money. The judge, Michael Argyle, wanted to make an example of these three men, with their long hair, seemingly radical ideas, and vibrant clothing. Members of the jury were almost entirely over the age of 50, and seemed to feel little sympathy for the editors from across a cultural and generational gulf.

One after another, witnesses were interrogated over the content of the magazine and the effect it might have on young minds—even whether the cover illustration might “turn” a heterosexual young woman into a lesbian. Among them were psychologists, teachers, writers, and principals, who were all asked time and time again, whether this material would indeed corrupt the minds and morals of schoolchildren. Some said yes, others thought the suggestion was laughable. In court, Anderson responded: “It was never my intention to do any such thing. Quite the opposite, in fact.”

A particular source of contention was a comic strip by Robert Crumb, adapted by Vivian Berger, one of the teenager contributors. In it, the children’s character Rupert the Bear is shown graphically “deflowering” his girlfriend, known as “Gipsy Granny.” It is not clear whether the woman, whose upper half isn’t shown, is conscious or consenting. In essence, Neville said later, the establishment was “deeply morally outraged by school children talking about teachers having erections or demythologizing Rupert Bear. They were absolutely freaked out by the fusion of sex, drugs, rock’n’roll, and schoolkids all in dayglo.”

As the prosecution team made reference to the men’s lifestyles, long hairstyles, and language, the defendants feared that Anderson’s sexuality would become a point of contention. Homosexuality had been decriminalized a few years earlier, but was still often conflated with degeneracy and even pedophilia. The prosecuting counsel Brian Leary seemed to know that Anderson was gay, Anderson said, and made knowing, though not explicit, references to it, designed to throw the defendant off-guard. Dennis explained: “Now this was a schoolchildren’s issue and while Jim wouldn’t have touched a schoolchild if you put a gun to the bastard’s head, that was still not what a jury would think.”

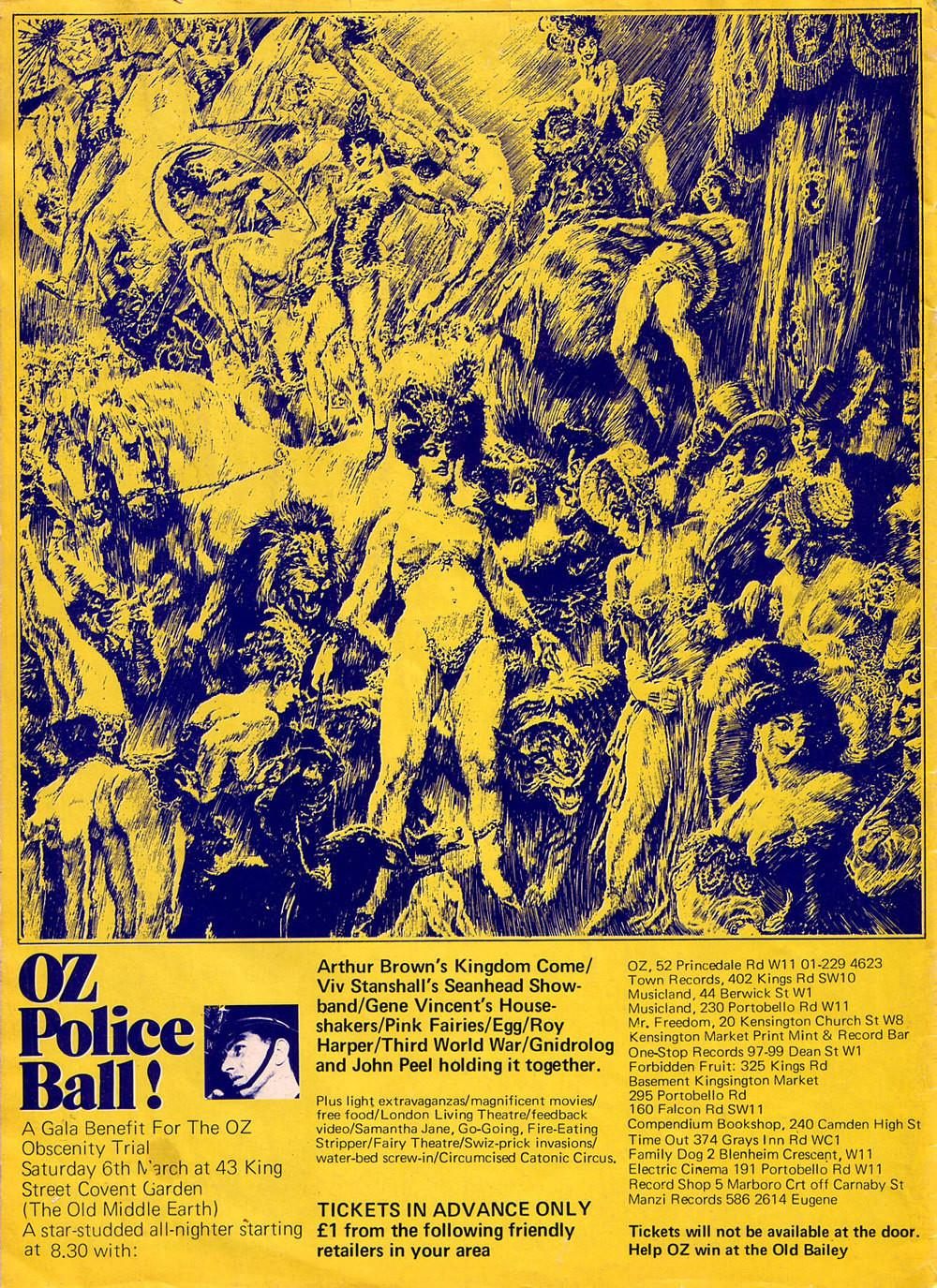

The case received unprecedented public attention, sparking headline after headline and thinkpiece after thinkpiece. At least part of this furor was due to the deliberate efforts of OZ and its “friends.” “Press kits” were put together for reporters, and outside the trial, people sold buttons and t-shirts of a topless woman, emblazoned with “OZ obscenity trial.” These had the dual function of helping to pay the magazine’s many expenses and raising awareness of the trial. Famous supporters also chipped in: A gallery on the King’s Road hosted a fundraising exhibition (“Ozject d’Art”) with works from Yoko Ono, David Hockney, John Lennon, Germaine Greer, and many others. Lennon even released a charity single, though it failed to take off.

The Times of London received more letters about the trial that summer than they had about the Suez crisis in 1956. “Opinion among our correspondents has been, roughly, equally divided for and against the defendants,” the editors wrote. Some chastised the Times for their lack of support for the magazine. Others were firmly on the side of the establishment. A letter writer called Bernard V. Slater labeled the magazine “sex propaganda,” while another who went by A. D. Faunce proclaimed that “Pedding a product harmful to the minds of children seems to me as antisocial as pushing drugs. Society has a duty to protect the young.”

What seemed to really rankle people, however, was the wastefulness and lack of common sense displayed by the trial. The 1959 Obscene Publications Act was, in its origin, an attempt to stamp out hardcore pornography. OZ might have been obscene, but it didn’t seek to be pornographic. Representative of some of the complaints, a letter by a Times reader named Laurie Kuhrt called the case “a triumph of injustice,” with “the pornographic industry continuing to thrive while OZ is threatened with bankruptcy.” Later, the New Law Journal described the case as without purpose, with “no less than 27 working days of a court” dedicated to a trial that resulted in “no substantial improvement of the law relating to obscenity, and certainly no other advantage to the public interest.” It was, in short, a colossal waste of time.

On Wednesday, July 28, members of the jury retired for three hours and 43 minutes. When they returned, a majority of 10 to one found the editors guilty of four of the five charges—publishing an obscene article; sending obscene articles in the mail; and two counts of having obscene articles for publication for gain. At the close of the trial, they were hauled off to the psychiatric ward of Wandsworth prison, where their long hair was shorn. Eventually, Neville was sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment; Anderson to 12; and Dennis to just nine months. The two Australians were recommended for deportation. Outside the Old Bailey, protesters clashed with police, burned an effigy of the judge, and set off smoke bombs. (The following day, they would be immortalized in an Express tabloid headline: “The Wailing Wall of Weirdies.”)

In the end, the editors served barely a week in prison. A successful appeal found that the judge had grossly misdirected the jury, amid a number of other miscarriages of justice. The convictions were overturned. A fine of £1200 was reduced to £50, the deportation recommendations were lifted, and the men walked free, wearing long, extravagant wigs.

Afterwards, circulation of OZ soared, and then nosedived. Neville’s heart, he said, was no longer in it. “Somehow in packaging our defense I felt I was becoming more and more a propagandist and less and less of Richard Neville hanging out in London, working with a group of people that I liked and respected, trying to give writers and cartoonists a platform—which was basically what OZ was about.” Being forced to justify their work on high moral grounds put a dampener on OZ’s spirits, he said. In November 1973, facing bankruptcy, the magazine folded, and the three instigators moved on with their lives.

For decades, copies of the magazine were few and far between, hard to find, and prized by collectors. Then, in 2014, OZ was given back to the public through a collaboration between Neville and the University of Wollongong, in Australia. Now, every issue is available online, with its obscene comic strips, sporadic typesetting, and genuinely revolutionary fervor on show for all to see.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook