Why 19th-Century Paris Had a Museum Full of Copies

Innovation and originality weren’t yet in vogue.

In 1872, a visitor to one part of the sprawling Palais de l’Industrie, on Paris’s Champs-Élysées, could climb a grand staircase decorated with tapestries and porcelain vases from the finest French ateliers, before coming face to face with the majesty of Raphael’s Disputation of the Sacrament.

Well, not the real thing—that fresco was and is irrevocably fixed on a wall of the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace—but a rather well-executed copy by one Monsieur Tiersonnie. The painting, depicting the Holy Trinity overseeing the sacrament of transubstantiation*, was surrounded by other replicas of the Italian Renaissance master’s work.

“Entering the vast salon,” wrote Louis Auvray, correspondent for Le Moniteur des Architectes, in 1873, “you could believe yourself to be in the Vatican.”

The Musée des Copies (Museum of Copies) was created in 1872, and opened to the general public the following year. Located in the since-destroyed grand exhibition hall built for the 1855 World Fair, it united around 150 reproductions of the finest paintings in Europe. Charles Blanc, director of fine arts for the French government, had personally championed the project, and commissioned copies executed by both well-known and lesser-known artists.

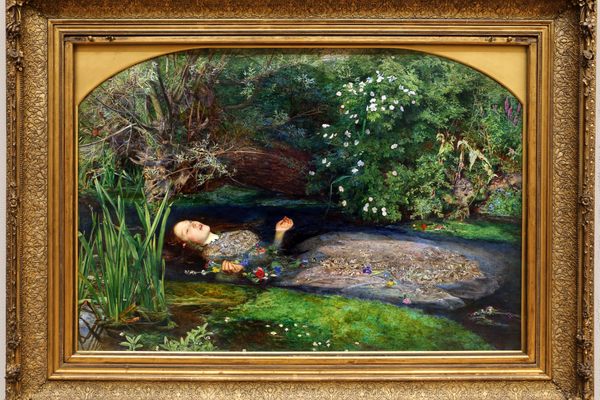

At the time, a museum of knock-offs would have seemed less strange than it does today. Replicating famous paintings had an important place in 19th-century France. There were days designated for copying at the Louvre, and the halls of the museum filled with men and women alike, behind their easels. “The whole formation of artists,” says historian Sevérine Sofio of the French National Center for Scientific Research, “was based on the copy, right up through the mid-19th century.”

Students were expected to master the style of artists who had come before—the Old Masters—and learned by replicating their work. At the time, the French art world had a particular reverence for classical art and Italian Renaissance painting.

The luckiest or best art students received the Prix de Rome to study in Italy for five years, which usually involved sketching their way through countless monuments, churches, and museums. The fourth year of study was explicitly dedicated to producing a copy of a masterwork suitable to be sent back to France to decorate Versailles or hang in the École des Beaux-Arts (the national school of fine arts). Such works comprised a study collection for students who could not go to Italy—and no one had high-resolution photographs to consult.

Practicing and respected painters also continued to make copies as a sort of continuing education. Some of the painters who would go on to form the Impressionist movement had trained in this traditional way. Édouard Manet first met Berthe Morisot (who married his brother, Eugène) while she was copying a Rubens in the Louvre in the late 1850s.

Expert copying was a valued skill. Some artists produced copies for a living, for the private market and for the state, including portraits to hang in embassies and in public buildings. Occasionally, copies of original works made it into the prestigious annual exhibition, the Salon de Paris.

The idea of a public museum dedicated to copies had been floated from time to time, and not just as a learning tool. Napoleon had assembled a grand collection of looted original masterpieces from conquered nations. Many were reclaimed after his defeat, but the memory of having the finest art in Europe all in one place—in Paris, specifically—whetted the French appetite for such a collection, even if it was a simulacrum. The arts community also began to understand the need to preserve works, or at least document them somehow.

However, even as the museum finally gained a champion in Blanc, tastes were beginning to change and the form was becoming passé.

“The 1860s and 1870s were a progressive time,” says Sofio. “There were a lot of artists who had a new vision of art which was based more on innovation.”

The École des Beaux-Arts underwent a major curriculum reform in 1863, and beginning that year students were judged less on their ability to ape the Old Masters and more on the basis of the originality of their compositions. The same year, the Salon des Refusés (literally, “exhibition of the rejects”) had drawn large crowds to see work by artists left out of the Salon de Paris—including the avant-garde painters who sought to capture the feel of their subjects rather than literal likenesses. We know them today as the Impressionists.

Rather than discourage Blanc, these changes pushed him to a greater urgency to assemble a sort of reference library of classical painting. “It’s necessary for our young painters to be in proximity to the imposing and formidable, if not the great masters, at least in their image,” he wrote in the daily newspaper Le Temps in 1847. He believed what he called his “universal museum” would reinforce the “correct” style for young artists, and that paying them to make the copies would further reinforce their commitment.

To fill his museum, Blanc took some of the paintings from the École des Beaux-Arts. Amid no little controversy, he also directed large sums from the state’s arts budget to the commissioning of yet more copies—eventually spending more on this than he did on supporting new work.

Critics received the finished museum with some ambivalence. A reviewer for the newspaper L’Univers illustré judged that of the replicas, “one quarter are excellent, one half mediocre and a quarter horrible … as imperfect as they are, they have the merit of familiarizing the originals with those who have not seen them.”

“Velasquez would tear out his hair,” wrote Albert Wolff in Le Figaro in 1873 “Raphael would let forth groans that would attract the attention of passers-by.”

In the end, it was politics, not critics, that ended the brief life of the Musée des Copies after less than two years. A new government relieved Blanc of his post in December 1873. His replacement, the Marquis de Chennevières, convened a committee to plan the dismantling of the museum his very first week in office.

To Blanc’s lasting bitterness, the replica paintings were unceremoniously dispersed, most back to the École des Beaux-Arts, others to regional museums around France.

Multicolor engravings and increasingly sophisticated and accessible photography further contributed to the declining importance of the copy in France’s art world. Blanc’s museum—which he expected to be a timeless monument to posterity—faded to no more than a curious footnote in Paris’s long artistic history.

Correction: This article originally identified the sacrament of “transubstantiation” as “transfiguration.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook