Peek Inside a Private Clock Museum in Austria

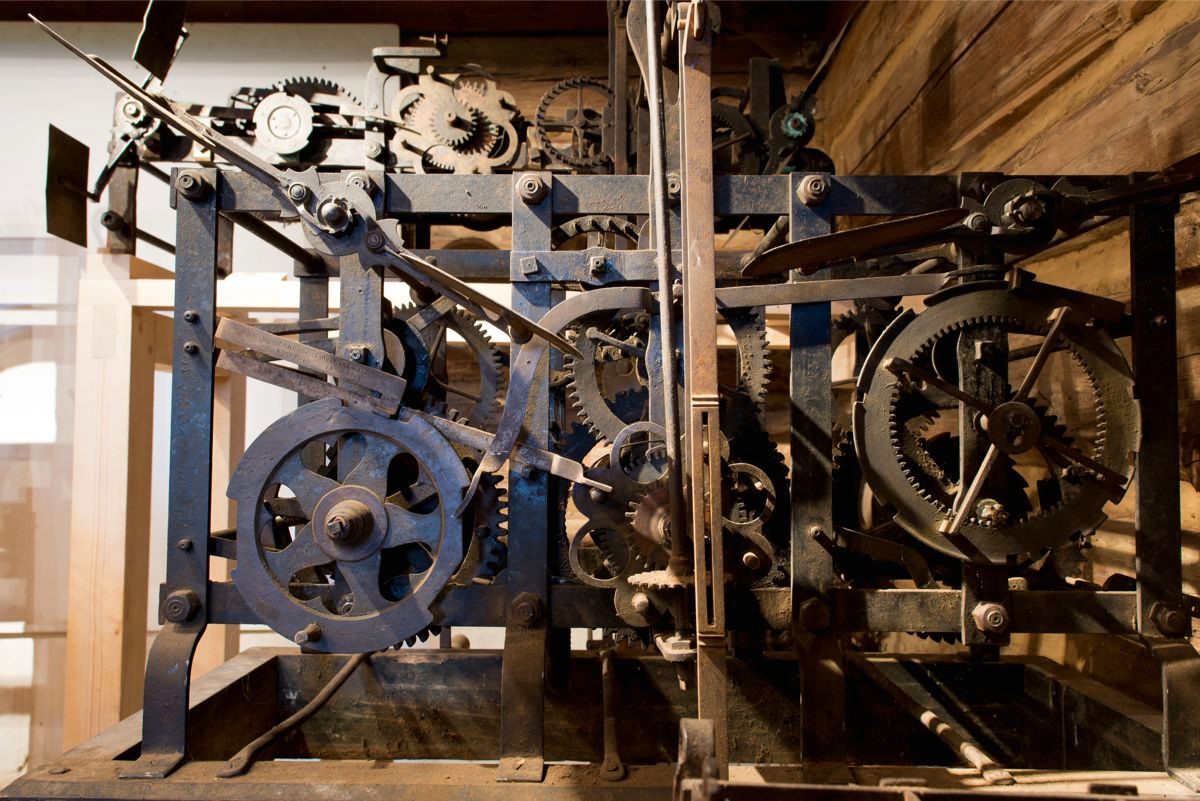

Details of a late Baroque tower clock made in the second half of the 18th century, from Upper Austria. (All photos: Yvonne Oswald)

The Uhrenstube Aschau, a little-known private clock museum in the sunny hills of Austria’s Burgenland region, is not easy to find. But after extensive phone explanations by its owner Wolfgang Komzak and two wrong turns, the historic farmhouse filled with clocks in the remote, lovely village of Aschau was finally located. Komzak was waiting outside a complex of early 19th century buildings with rye straw roofs.

Komzak, now retired, is one of the world’s most sought after experts for the renovation of tower clocks. His collection of rare clocks, mostly from the 15th to the 19th centuries, is the largest private collection of its kind in Middle Europe. He has traveled all over Europe in search of outstanding pieces, and currently has about 70 of these majestic clocks, all of which he knows how to assemble.

Wolfgang Komzak posing in front of the ancient granary storing part of his collection.

Komzak’s story is fascinating. He and his mother fled the east after World War II and found shelter in a large house in the Austrian countryside. His mother worked as a seamstress to provide for their living, and he was frequently left to himself as a small child. He spent much time in the house’s vast attic. One day, he found a tower clock, which he destroyed by accident while playing with it. When he tried to reassemble it, he could not succeed. This caused a lifelong fascination with the machines.

He started to collect tower clocks while working as a civil engineer. By the time Komzak retired, he had become a well-known specialist in repairing the clocks, and had been asked to become a member of the Swiss, French, German, British, and Austrian Chronometric Societies.

Eventually, he decided to set up a private museum in the small village of Aschau. He renovated the historic farmhouse to show his collection in several little houses, and also installed a forge and a precision workshop for restoration of his clocks or others that are brought to him to repair. The museum was opened in 2003.

The painted dial of a small Gothic period house clock from 1573, made in southern Germany.

While working in his forge on the restoration on a beautiful and delicate baroque tower clock rescued in Southern Germany, he recalls some of his travels. It turns out that he is often called in when churches are renovated or attics are emptied. More than once, he has managed to rescue rare pieces that would have ended up in the trash, and brought them to life again. During the tour, he provides affectionate description of each detail concerning the story of his clocks.

During lunch in Komzak’s cozy parlor, heated by a tiled stove, he tells of a darker era of the museum’s history. In the summer of 2013 part of the house was burned down by a mentally ill boy. Komzak escaped death by sheer luck. The house caught fire quickly, due to its straw roof, but he was trapped in a room with windows too small to escape from. Thanks to the Austrian fire brigades, he made it out at the last moment.

After the fire the main house was re-roofed with rye straw.

Part of his collection was destroyed and he still grieves for a rare Gothic period clock that could not be saved. Insurance was reluctant to pay for his losses. But Komzak fought his way back and the museum reopened in 2014.

Despite many awards Uhrenstube Aschau is hardly known, even in Austria, but it is well worth the journey. Tours are by appointment only, however Komzak is not easy to reach thanks to the bad mobile phone connections in the hills of Burgenland. But the museum sees quite a few members from different Chronometric societies around the world, who recognize what a special place it is. Below, peek inside this intriguing private clock museum.

This clock was made by Ignaz Berthold in the late 19th century in Styria/Austria.

A baroque clock from the early 18th century, Upper Austria.

Wolfgang in his forge preparing parts of a historic watch for restoration.

The workpiece at the anvil being forged in form.

This tower clock was made by Sándor Ferencz in Hungary in 1912.

Handling a coal forge requires deliberate skills.

A small tower clock from the late 17th century made entirely from wood, probably in Switzerland.

Spare parts of ancient tower clocks are waiting for their restoration.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook