How the Enchanting, Elusive Pink Fairy Armadillo Became One Scientist’s Obsession

A conservation biologist in Argentina once hosted one of the animals in her living room, but finding them in the wild has proven far more difficult.

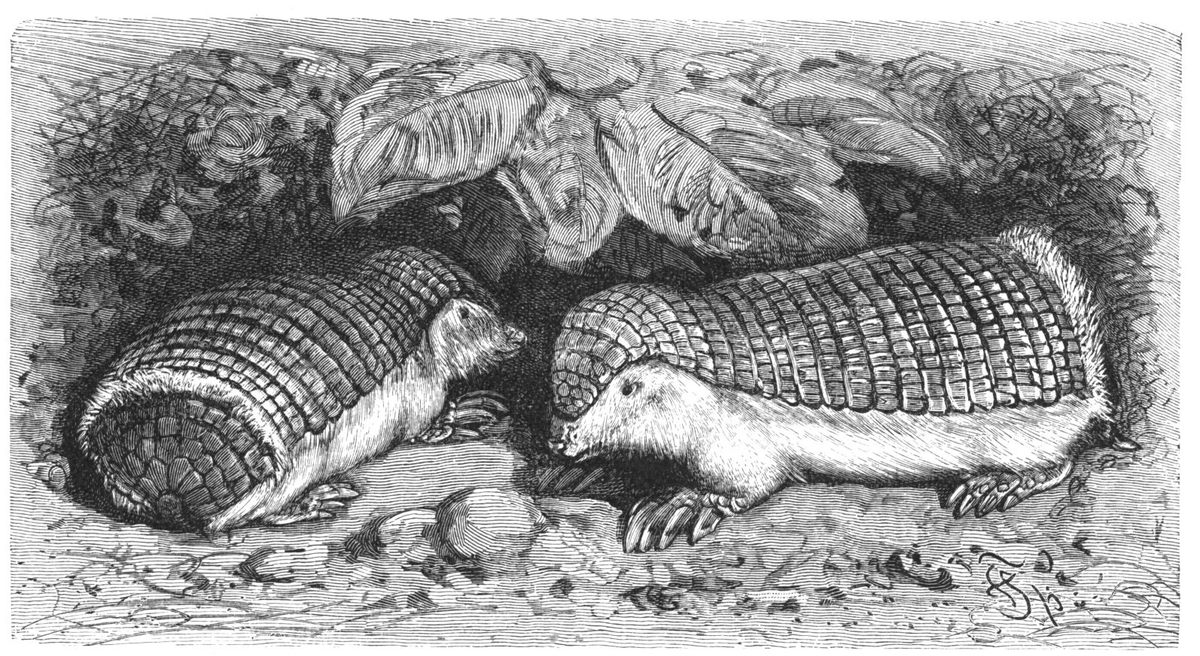

In the arid desert of Argentina’s Mendoza Province, Mariella Superina waits patiently for a fantastic creature to emerge from its lair beneath the sands. Her quarry, the pink fairy armadillo (Chlamyphorus truncatus), looks like it could have scurried straight out of the illuminated pages of a medieval bestiary. The animal’s shell, paws, and tail are a vibrant bubblegum pink that contrasts with its silky, milk-white fur and black eyes. About the size of a hamster—a mere six inches from head to tail and weighing just a quarter of a pound—it’s the smallest of all armadillo species. It’s found only in Argentina, in a broad swathe of sunbaked scrubland that stretches from the foothills of the Andes to the coastal province of Buenos Aires. And that is about all we know of these wondrous animals. “They are a total enigma… We don’t even know if they are common or rare,” says Superina.

In fact, some people doubt whether they’re even real. “The first question that hits on Google is, ‘Do pink fairy armadillos exist?’” says evolutionary biologist Simon Watts, author of We Can’t All Be Pandas (Ugly Animal Preservation Society). “‘Pink fairy armadillo’ does frankly sound fictitious.”

Watts, whose podcasts and tv shows champion the less charismatic members of the animal world, doesn’t count the pink fairy armadillo as one of his unsung uglies—between its cotton candy colors and curious name, he says, “people tend to be fascinated when they hear of them.”

Instant fascination was certainly Superina’s reaction the first time she saw one of the tiny mammals. “I was speechless,” she says. “At that moment I knew I wanted to learn everything I could about it. It became an obsession.”

Originally from Switzerland, Superina began studying armadillos in western Argentina 25 years ago. Today, she leads an international team that monitors global populations of anteaters, sloths, and armadillos but, thanks to her pink fairy armadillo obsession, she has also become the leading expert on the diminutive and enigmatic animal. She even hosted a live pink fairy armadillo—which turned out to be a real diva—in her living room in the name of science.

Studying the animal in its natural habitat, however, has eluded her—and everyone else. For centuries the armadillo has evaded the most determined scientists; even Charles Darwin failed to collect a specimen during his visit to Argentina. The pink fairy remains as mysterious as its name suggests because of its subterranean lifestyle, the result of adaptation to a changing environment millions of years ago.

That’s when global climate patterns shifted, transforming the Andean foothills from grasslands into semi-arid deserts. As its habitat became less hospitable, the pink fairy’s ancestor retreated from the surface, evolving into a burrowing, or fossorial, animal. “Burrowing habits tend to appear when habitats become open, going from tree cover to grasslands or deserts, or when they get really hot,” said the University of Oregon’s Samantha Hopkins, who studies small mammal evolution, in an email.

Underground, in the absence of predators, most of the pink fairy’s shell softened, losing its defensive function. It serves instead as an air conditioning system: In hot weather, the armadillo flushes its shell with blood, radiating heat and cooling down its core body temperature. Using its brawny foreclaws, the armadillo burrows through the sandy soil hunting for worms and insects. As it digs, it uses its armored butt plate to compact the loose soil in its wake, shoring up tunnels to prevent collapses.

The elusive armadillo does appear above ground, when excessive rainfall—unusual in this desert region—floods its burrows. But the sight of a pink fairy is so rare that, “Octogenarians who have lived all of their lives in these rural areas (may have) seen this animal only once or twice,” says Guillermo Ferraris, a provincial ranger who works primarily in wildfire management. “But they never forget it.”

When the pink fairy armadillo does leave its subterranean sanctuary, it encounters a bewildering and perilous world. Towns and vineyards are gradually replacing what was once vast scrubland. Herds of feral goats overgraze vegetation and compact the soil under their hoofs, hindering the armadillo’s ability to dig its burrows. Oil fields and asphalt roads busy with trucks and cars bisect the desert landscape, isolating armadillos from one another.

Out of their element, pink fairy armadillos are highly vulnerable to speeding cars and predators, including dogs and cats. Sometimes, however, Superina gets a call: A live armadillo has turned up. She rushes to the scene to collect data vital to understanding the species. “It’s always a magical experience to see a pink fairy armadillo in the flesh, up close, but I put my awe to one side because we have to work fast to avoid causing any unnecessary stress, so we can immediately release the animal,” she says.

On one occasion several years ago, however, she did take one of the rescued animals home. The provincial department of natural resources had requested her help: The idea was that, by studying the basic needs of an animal under her care, Superina could improve the chances of successfully rehabilitating injured armadillos, so they could be released back into the wild. Despite being obsessed with the armadillo, it was not an easy sell for Superina.

“At first, I refused because these animals are very sensitive and usually die within a few days,” she says. “But then I realized that, for their conservation, we need to understand if it’s possible to keep them alive in captivity.”

Even now, as she recalls the event, she stresses that it’s not only illegal but also unethical to keep the animals as pets. Undertaking her role as armadillo caregiver required a special permit—and some serious home renovation. Ferraris, Superina’s partner, built a huge, sand-filled terrarium for the armadillo in their living room, creating natural hiding places and setting up infrared cameras to record its behavior. “It was quite an experience,” says Superina, laughing. “Our lives revolved around this pink fairy armadillo. We couldn’t go anywhere because we had to be in the house every night to care for it, and study its behavior.”

The unusual houseguest was rather demanding. Superina brought it a variety of insects and worms, but the pink fairy turned up its pale nose at everything offered. Undeterred, the scientist tried one idea after the next. Finally, 36 meticulously-prepared recipes later, the armadillo tucked into a meal that apparently satisfied its gourmet tastes: a premium brand of cat food mixed with finely mashed banana, and sprinkled liberally with insectivore pellets. The finicky fairy would leave its burrow to eat the food at exactly 9 p.m. each night.

“If only the slightest thing was moved in the terrarium, the armadillo would start scurrying around making this eerie, high-pitched scream until everything was put back exactly in the same place,” says Superina.

Her fussy subject, alas, lived only eight months, but the experiment provided valuable information about how to care for injured individuals during rehabilitation. Learning about the animal in the wild, however, remains difficult.

The pink fairy is particularly problematic because standard field observation techniques are of limited use. Radio transmitters used for tracking mammals, for example, are usually attached by placing collars around the neck; the armadillo’s body shape makes this nearly impossible. So Superina decided to use special glue to fasten a tiny radio transmitter to the pink fairy armadillo’s armored rear.

When a farmer found one of the animals out and about, “We went and attached a transmitter and released it back into the desert,” Superina says. “And off it went, looking like a little bumper car with the antennae trailing behind.” The next morning they found the tracks in the sand and began following the signal to look for the animal—only to discover that the transmitter had fallen off while it was digging itself back underground. She’s now exploring other options to track the armadillos, including one that relies on an animal that is usually more foe than friend to the pink fairy: the dog.

Superina is working with an organization that has successfully trained scent detection dogs in Africa to track down another secretive, armored insectivore: the pangolin. Superina hopes that a dog could be trained to locate pink fairy armadillos so researchers can fit them with improved radio transmitters.

For Superina, the search for the pink fairy has taken on an added sense of urgency. So little is known about the species that scientists can’t say whether it’s endangered—or how climate change is affecting it. “We just don’t know how these animals are going to cope,” Superina says.

For now, she waits, with a tiny transmitter at the ready, for the next appearance of her obsession. Tracking the animal underground will be a scientific milestone, but, perhaps more importantly, says Superina, it will be “a small step to better understanding this species, its needs, and what it needs from us for its conservation.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook