A Day in the Life of a Pennsylvania Plant Detective

Researchers are comparing age-old herbaria with muddy riverbanks to track decades of ecological change.

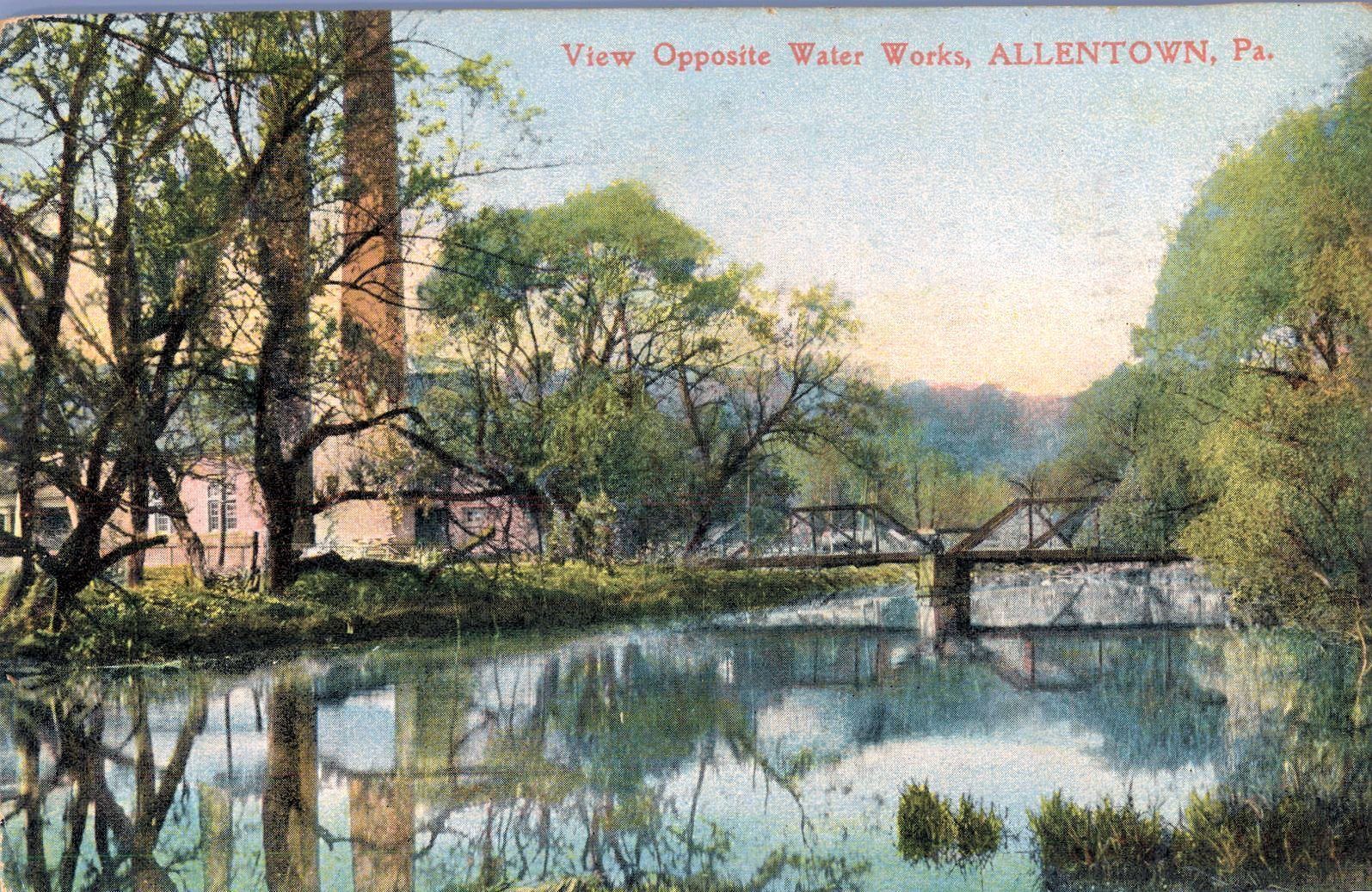

There were no more trains chugging past—or even tracks, for that matter—but Richard Niesenbaum was searching anyway, looking for the path of a railroad that once traced the contours of Cedar Creek in Allentown, Pennsylvania. He was pretty sure he had found it, on a marshy riverbank near the site of what was once a quarry. Niesenbaum is a botanist at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, and he was helped greatly in this question by the fact that his predecessors, plant-collectors of yore, were pretty fastidious record-keepers.

Niesenbaum has spent hours with their notes—and he even fought to save them—because this brainy chicken scratch is full of clues that he uses to hunt for plants that may have vanished from the Pennsylvania landscape.

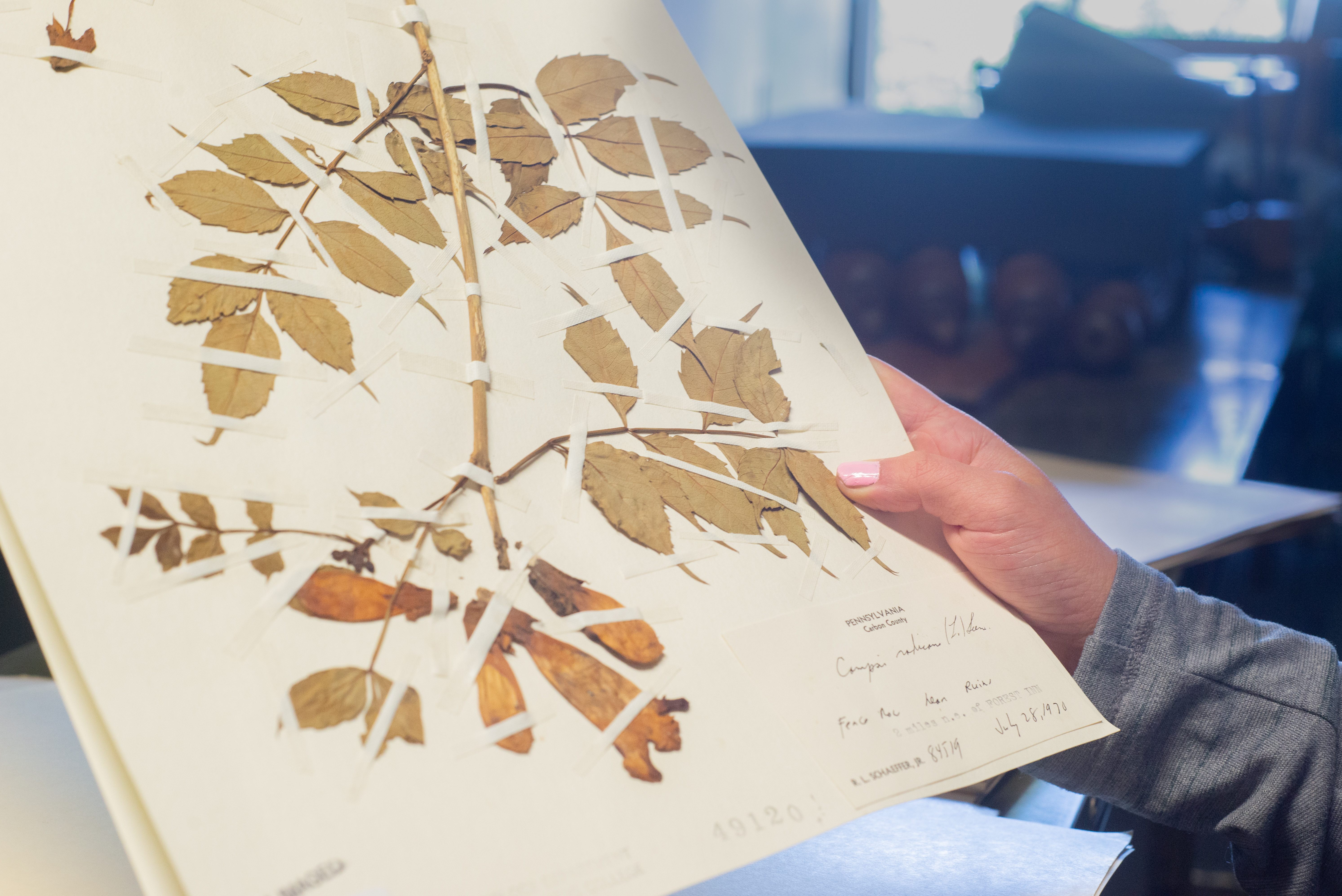

The university’s herbarium—a collection of leaves pressed flat and mounted on archival paper, with accompanying notes—is 60,000 sheets strong, so it takes up a fair amount of storage space. Some institutions are offloading their plant collections, Niesenbaum says, but he went to bat for this one even before he knew exactly how it might be useful. “Something inside of me, said, ‘We’ve got to save this thing,” Niesenbaum recalls. “There’s got to be value in it.’”

Soon enough, he found it. A handful of researchers have been looking to university and library herbaria as repositories for data about long-term ecological change, especially as industrialization and urbanization have reshaped landscapes around where the plants were collected.

That sounded familiar to Niesenbaum: Allentown has changed a lot since some of these specimens were collected, in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Now, 51,496 of the university’s pressed plants and marginalia have been digitized as part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project—an effort to track flora along the urban corridor between New York City and Washington, D.C.

To build on that work, Niesenbaum decided to put boots on the ground (or riverbank), and return to the historic collection sites to see whether the plants that once thrived there have continued to live on, even as the world has changed around them. Earlier this summer, he and Lindsay Press, a student researcher, began looking through the herbarium specifically for things that might have changed—such as plants that are now classified as locally extirpated, endangered, threatened, or rare. They wondered what those collection sites look like now.

That’s how Niesenbaum found himself splashing into Cedar Creek, looking for a rare sedge and aquatic grass.

The now-vanished railroad was key. At the time the old samples were collected, railroad rights-of-way had a tendency to preserve the native landscape right around them, which made them attractive collection sites. Plus, the previous botanist, prolific collector Harold W. Pretz, working in 1924, had been generous with details. He wrote down intersections, mileage from a point in town, and proximity to the quarry, which Niesenbaum confirmed through aerial photographs. “We could draw intersecting lines to get a search area based on that,” he says. In other instances, where land has been transformed beyond recognition, he’s employed county tax records and real estate databases.

Those clues led his team to a marshy stretch of Cedar Creek, a tributary of the Little Lehigh, where they spotted an old wooden trestle and a handful of rail ties still in the ground. It’s an active place for trout, and a reservoir for local drinking water. These riverbanks are within a public park, but this portion doesn’t get a ton of foot traffic. Occasionally, Niesenbaum crossed paths with people working at the nearby food bank, who “didn’t seem to mind us botanizing in their backyard.”

At first, things looked fairly promising. “When we first popped into the site, we got so excited, because the first thing we saw was a sedge,” Niesenbaum says. He thought it might be Carex tetanica, which is threatened in this part of Pennsylvania. (It looks vaguely grass-like, but with triangular stems instead of blades.) He also thought he saw the wetland grass they were after, Potamogeton zosteriformis, which is listed as “rare.”

He slogged into the water to get a closer look and to grab a tuft for the lab. “It was an impromptu jump in,” Niesenbaum says, “with hiking boots that got soaked.”

Niesenbaum’s enthusiasm was understandable—at least for a botanist. “Grasses in streams in Pennsylvania are not super-abundant now,” he says. When nutrients from, say, lawn fertilizer take over bodies of water, algae follows, choking out the native grasses that once lined the region’s waterways. The sightings were a good sign. But when he got the samples back to the lab and continued growing them in water, they turned out to be much more common varieties—likely Carex lurida and Vallisneria americana, respectively.

It was a disappointment, but Niesenbaum wasn’t too bummed out. Though he did not find what he set out for, “the good news is that we found a native plant,” he says.

That is notable because, even though the park appears more “natural” than a vacant lot or swath of asphalt, it’s still a managed ecosystem, and changes to the way land is used leave ripples far and wide. The area around the park is a floodplain, Niesenbaum says, and its banks are a riparian buffer zone that have been dominated by non-native plants, such as Japanese stiltgrass, knotweed, and the common reed. These are a mixed bag. They do help protect the stream from runoff and the land from flooding, but they’re also “crowding out rare and threatened plant species that would normally grow on the side,” Niesenbaum says. He was glad to find a little native grass holding its own. “At least a common wetland plant is still common, as we see the decline in wetlands.”

The project is going to continue, “but to really move this forward, we’re going to need a team of people who are really field-hearty,” Niesenbaum says. The work can be tedious and slow-going, and it’s tough to spend all morning looking for a sedge, only to find the one you’re not looking for.

The payoff is worth its though: an ecological record hidden in plain sight. Over time, by comparing its holdings with the present day, the university’s herbarium may be able to provide a leaf’s-eye view of a century or more of sweeping changes. It could show, for instance, how climate affects the timing of flowering or leafing, both locally and across the corridor. “You have to start to zoom in first,” Niesenbaum says, “and from there, get the bigger patterns.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook