The History of Race, Performance, and Drag Intersect in a Rare Photo of Thomas Dilward

Dilward performed with all-white minstrel troupes that otherwise excluded black people.

Today in Brooklyn, New York, the southwest corner of Court Street and Remsen Street is home to a vitamin store, a law office, and a pizzeria. But in September 1862, during the second year of the Civil War, the corner was home to Christy’s Opera House, a theater that put on minstrel shows in which white men blackened their faces with burnt cork in a racist caricature of African Americans. Christy’s troupe of 16 had one notable exception: a black performer named Thomas Dilward, who used the stage name “Japanese Tommy.”

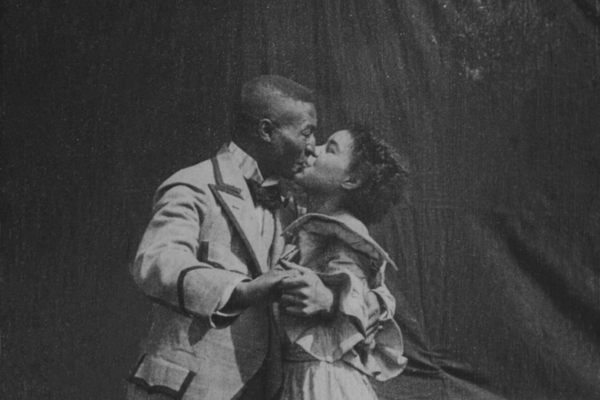

Dilward was one of the first African-American performers to tour with white minstrels, who typically excluded African-American performers from their shows, John G. Russell, a cultural anthropologist at Gifu University in Japan, writes in an email. Dilward often performed in drag, according to Errol Hill and James V. Hatch’s A History of African American Theatre. He made history as a member of these all-white troupes, even as he inherited the troubling history of a genre built on racist caricatures and exclusion. A rare carte de visite of Dilward wearing a ruffled dress, white gloves, and a bonnet was sold to a private collector by Cowan’s Auctions on February 20. “I have seen this carte de visite a long time ago at the Harvard Theatre Collection,” Krystyn Moon, a historian at the University of Mary Washington, writes in an email.

Dilward (who sometimes appears as Dilverd or Dilworth, among other permutations) was born in Brooklyn, New York, in the late 1830s. He was a little person, standing approximately three feet six inches tall, and first began performing with Christy’s Minstrels in 1853, according to Moon’s book Yellowface: Creating the Chinese in American Popular Music and Performance, 1850s-1920s. The all-white troupe was formed in Buffalo but performed throughout New York City, once running for a seven-year engagement at Mechanics’ Hall on 472 Broadway in Manhattan, which is now a six-story condo.

“How and when Dilward got the name ‘Japanese Tommy’ is unclear,” Russell says. “Some suggest he adopted [it] when delegates of the first Japanese Embassy visited the U.S. in 1860, but it appears he was already performing under that name with Christy’s Minstrels as early as 1853.” Commodore Matthew Perry opened Japan to American trade in 1853, leading some scholars to suggest that occasion might be the origin of Dilward’s stage name, Moon says.

In 1884, Dilward performed in a skit, “Fun in a Chinese Laundry,” that invited white audiences to laugh at both African-American and Chinese people at once, writes Josephine Lee, a scholar at the University of Minnesota, in The Japan of Pure Invention. Troubling portrayals of people of Asian descent were widespread at the time; the anti-Chinese sentiment that bubbled up in California in the 1860s had spread nationally by the 1870s, and in 1882, President Chester Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

After initially being cast for his stature, Dilward established himself as an acclaimed and versatile performer who sang, danced, and played the violin, Lee writes. Drag performances were a staple of minstrel shows, and Dilward often impersonated operatic prima donnas, Hill and Hatch write.

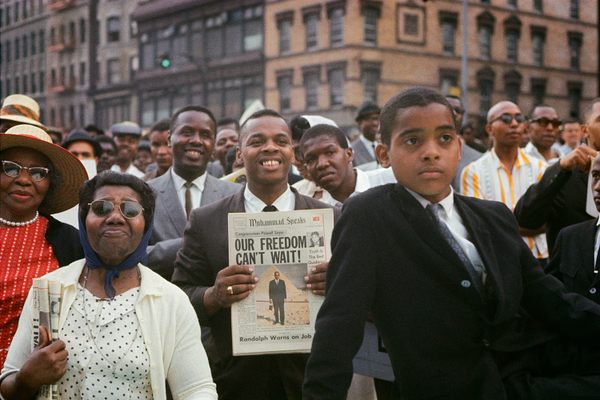

Though Dilward spent much of his early career in all-white minstrel troupes, he later joined several of the African-American minstrel troupes that emerged after the Civil War. In 1870, Dilward joined the troupe of the formerly enslaved entrepreneur Charles B. Hicks. “Black-on-black minstrelsy was more attractive to black entertainers, because they saw it as a way of gaining a foothold in the more remunerative and mainstream white theaters,” Monod writes. Black troupes still performed white stereotypes of black people, but their performances allowed black people to gain some control over how they were portrayed on stage, and there were few other ways to make a living as a black performer, Moon says.

Dilward’s last recorded show was with the Criterion Minstrels on March 5, 1887, according to a white minstrel producer named Edward Le Roy Rice. Dilward died two months later, of asthma, and was buried in Evergreens Cemetery along the border between Brooklyn and Queens, according to his obituary in The New York Times.

Dilward’s remarkable, complicated life appears only in the margins of the historical record; he appears mostly as “Japanese Tommy” in the credits of various playbills of minstrel shows, and in the reviews of local newspapers. In 2016, the theater historian Caitlin Marshall unearthed more concrete traces of Dilward for her graduate thesis at the University of California, Berkeley. She found that Dilward registered for the Civil War draft, and that he sued a Manhattan restaurant for refusing to serve him because of his race. Once, he headlined a show called Don’t Fail to See the Little Man.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook