A Czech Museum’s 432-Million-Year-Old Plant Sprouts Surprising Information

A new look at the fossil shows plants of the era may have been greener and more vascular than we thought.

So far, 2018 is quite the interesting year for the Czech National Museum in Prague. During a major construction and audit of the building, officials discovered much of their five-carat diamond and 19-carat sapphire collection had been replaced with fakes. One sapphire, reportedly worth tens of millions of dollars at today’s exchange rate, was replaced with an artificially made stone, and another diamond turned out to be cut glass. They are still investigating the collection’s authenticity, working with police to uncover the heist details, and have tightened security since.

So, when museum scientists realized via a new study that one of the items in the collection, an unassuming petrified plant smelted into volcanic deposits, was one of the oldest plant fossils in the world and could produce oxygen, it came as a relief.

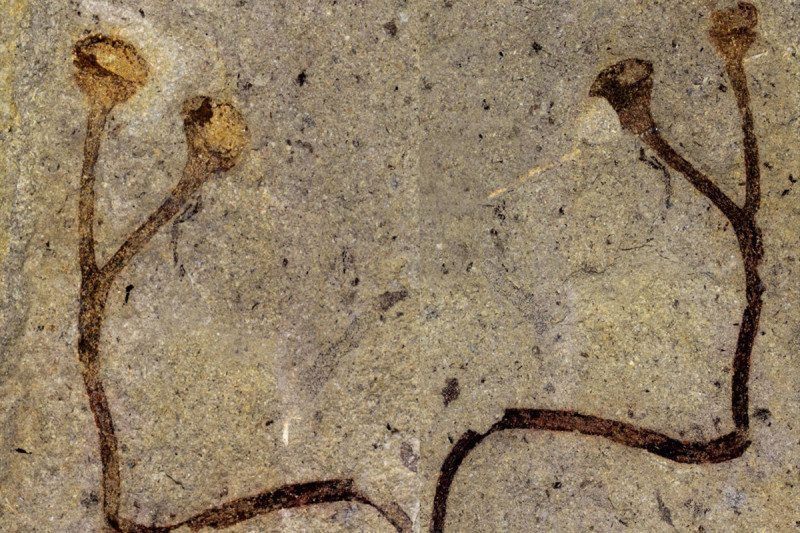

At six centimeters long, the 432-million-year-old plant, part of an extinct grouping called Cooksonia, is also one of the largest terrestrial plants of its age. The second-oldest Cooksonia fossil, which dates to approximately 425 million years ago, is just a few millimeters long.

In the early 19th century, Joachim Barrande, a French paleontologist and geologist, stumbled across the larger fossil stem around Loděnice village, which is located in Czechia’s central Bohemian region. The plant, along with much of his findings, became part of the National Museum’s collection. For years, it remained in a dark crate deep in the basement.

In 2011, while shifting around collections to prep for construction, paleontologists unearthed the prehistoric fossil. They traveled to where Barrande came across the stem to see what else they could learn about the fossil and potentially unearth others. They found similar Cooksonia fossils, but they were far smaller than the museum’s one. The small size of other Cooksonias proved to be a challenge for researchers.

“It was supposed that so small a plant could not have contained supportive, conductive or even photosynthetic tissues. Paleontologist Kevin Boyce even supposed that those first plants could not be green,” National Museum stated in a press release. In a recently published Nature Plants study from the Czech National Museum, the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the Charles University, and the Institute of Geology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, researchers overturned this thesis and concluded that “this Cooksonia plant’s body volume was sufficient for it to secure the basic functions of a vascular plant, including photosynthesis, the distribution of water and nutrients, and to be capable of independent life.”

The museum plans to put the fossil on display this fall—with guards watching, of course.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook