The Soviet ‘Red Passovers’ Where Jews Gave Thanks for Communism

Instead of celebrating freedom from Egypt, people celebrated liberation from capitalism.

“Wash off all the bourgeois mud, wash off the mold of generations, and do not say a blessing, say a curse.” In 1923, Moyshe Altshuler published this heretical take on the sacred pre-Seder hand washing ritual in Hagadah far gloybers un apikorsim, or “Haggadah for believers and atheists.”

Altshuler was one of many Soviet Jews in the 1920s and 1930s trying to convince their people to “wash off” what they saw as “the mold” of their religion. Communist artists, authors, and actors held Red Seders all over the nation, transforming the traditional Passover dinner in the hopes of turning observant Jews into ardent Bolsheviks.

“They are fighting Jewish tradition [and] Jewish observance, with humor, with mockery,” says Anna Shternshis, a Professor of Yiddish Studies at the University of Toronto and the author of Soviet and Kosher: Jewish Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. At the time, the early Communist Party was pushing Jews to abandon religion in favor of a secular Jewish identity. In the 1920s, Soviet Jews were still reeling from the brutal pogroms of the Russian Civil War and eager for a more protected life. Of all the participants in the war, the Red Army was the least violent and most protective towards the Jews, so they joined the Communist Party in huge numbers.

But there was a problem: although the Bolsheviks were officially against antisemitism, they hated religion of any kind, and the majority of Soviet Jews were strictly observant. The Communist Party’s solution to the problem, carried out by the Jewish section of the Bolshevik Party, was turning Jews into an ethnic group. The government supported Yiddish literature, Yiddish theater, and secular Jewish schools, but waged a fierce campaign against the Jewish religion itself.

The Passover Seder, a beloved springtime meal celebrating the Jews’ deliverance from Egypt, had no place in this new ethnic life. During the feast, every dish corresponds to a story, and children play games, sing songs, and ask contemplative questions. This was seen by the new government as an opportunity for political education. In 1921, the Central Bureau of the Party’s Jewish section instructed all local branches to organize Yiddish-language “Red Passovers,” public satires where the Revolution took the place of God, and leavened bread took the place of matzah. These Seders were mostly attended by Jewish youth, who often lived secular Soviet lives in public but practiced some Jewish traditions at home. They would attend Red Passovers before enjoying a feast of noodle pudding and matzah at their families’ traditional Seders.

Shternshis writes that it’s difficult to reconstruct the exact details of these celebrations, but a rough picture emerges from preserved Red Haggadahs and Shternshis’s interviews with Jews from the former Soviet Union. Some Red Seders made a point of handing out bread, a major blasphemy during Passover. Observant Eastern European Jews normally keep leavened food out of their homes and their bodies throughout the eight days of the holiday to commemorate their ancestors’ flight from Egypt, in which they did not have time to let bread rise.

One interviewee in Shternshis’s book said that, as students at a Yiddish school, he and his classmates were each given ten pieces of bread and made to compete over who could throw them the fastest into the windows of Jewish homes. “We enjoyed the game very much,” he told Shternshis, “especially when the old, angry women came out of their houses and ran after us screaming ‘Apikorsim!’” or ‘heretics.’”

The Party’s Red Haggadahs, published as pamphlets and supplements to Yiddish periodicals, parodied storytelling traditions to mock Judaism and promote Party ideals. Traditional Haggadahs often include a famous line that reads, “We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and Adonai, our God, brought us out from there with a strong hand and an outstretched arm.” One Red Haggadah instead praised the Bolshevik, or “October,” Revolution: “We were slaves of capital until October came and led us out of the land of exploitation with a strong hand, and if it were not for October, we and our children would still be slaves.”

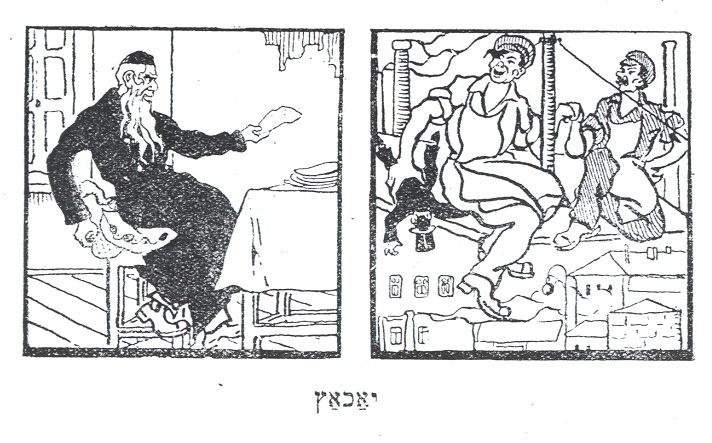

In another Red Haggadah, the tradition of tearing a piece of matzah in two described the proletariat tearing the means of production from the hands of the bourgeois, and the tradition of covering the matzah represented the revolution’s complete envelopment of capitalists. An illustration from the Hagadah far gloybers un apikorsim offers a particularly gruesome take on the Passover custom of eating a sandwich of matzah and bitter herbs, which typically symbolizes the bitterness of slavery. Instead, in the 1923 book, a giant Red Army soldier eats a sandwich consisting of French Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, and Jewish-Soviet opposition leader Yulii Martov.

In fact, these Haggadahs are full of enemies who are not the Pharaoh of Egypt. They are generally made up of a mix of Jewish and gentile figures. This was to avoid veering into either antisemitism or inter-ethnic resentment, Shternshis says. In a send-up of the tradition of burning leavened bread before Passover, one Haggadah describes the burning of landowners, Zionists, and army generals alike in the Communist Revolution a few years earlier. “Those who were already burned, shall never rise again, and as to those who will remain, we will sacrifice them and hand them over to the State Political Directorate,” the text reads.

Lines like these can read as haunting prophecies for a religious group who would be slaughtered in gas chambers less than two decades later, and executed as political enemies by Premier Joseph Stalin soon after. “I’ve had people tell me, ‘But it’s not funny. It’s so scary because they’re burning all these enemies, and look what happened to Jews just 17 years after that,’” says Shternshis. “And it is chilling. But [the writers] found it funny.”

By the 1930s, efforts like the Red Seders had created a widespread “Soviet Jewish secular culture,” Shternshis writes. They were so effective, in fact, that in the beginning of the decade, the Communist Party shuttered its Jewish arm because it was deemed unnecessary, and in 1935 the Party closed its Jewish Schools. “They decided by that time that the project of Sovietization of Soviet Jews was completed and they didn’t need any more events like [Red Passovers],” Shternshis says. After a decade of government-sponsored spoofs, Red Seders faded away. In the following decade, Stalin led a wave of violent antisemitism that attacked the new secular Yiddish culture, pushing Jewish culture further to the margins.

Today, the diaspora of Jews from the former Soviet Union are still feeling the impact of Red Seders and other anti-Jewish projects. “One thing that is universally noted is that they do not associate being Jewish with Judaism,” Shternshis says. In 2020, a survey of former Soviet Jews revealed that most saw language, ancestry, and the State of Israel as core parts of their Jewish identities, but considered religion only tangential.

This year, many former Soviet Jews and their descendants will abstain from traditional Passover, and many will celebrate it. But few will celebrate the holiday as they did in the 1930s: with parodies of Jewish songs and stories that raucously give thanks for the Russian revolution.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook